Nothing Much to Do: Why America Can Bring All Troops Home From the Middle East

Executive Summary

U.S. interests in the Middle East are often defined expansively, contributing to an overinflation of the perceived need for a large U.S. military footprint. While justifications like countering terrorism, defending Israel, preventing nuclear proliferation, preserving stability, and protecting human rights deserve consideration, none merit the current level of U.S. troops in the region; in some cases, the presence of the U.S. military actually undermines these concerns.

Quincy Institute paper No. 2 asserted that the core U.S. interests in the Middle East are protecting the United States from attack and facilitating the free flow of global commerce. These interests generate the following two primary objectives for the U.S. military in the Middle East: to prevent the establishment of a regional hegemon and to protect the flow of oil through the Strait of Hormuz.

The United States has no compelling military need to keep a permanent troop presence in the Middle East.

This raises the following questions: Does any country in the Middle East have the capability to achieve either of these objectives, or is any country within near-term striking distance of having such capability? What actions would the U.S. military need to take to tip the balance of capabilities against an adversary seeking either regional hegemony or to close the Strait?

Iran, Iraq, Saudi Arabia and Turkey could vie for Middle East hegemony…

The four possible contenders for regional hegemony are Iraq, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey. To achieve the status of military hegemon, one of these states would have to have the capacity to knock out at least two of the others. To achieve this would require their army to possess at least five core capabilities: 1) logistics capacity to supply an advancing army; 2) ability to defend moving troops; 3) ability to respond to unforeseen circumstances; 4) ability to execute complex combined arms maneuvers on the offensive; and 5) ability to maintain control of captured territory.

… but none of them would succeed

None of the four potential contenders in the Middle East has the requisite capabilities, and none has the plausible potential to rapidly acquire these capabilities in a way that would give it a relative advantage over its opponents.

… nor can they close the Strait of Hormuz

Completely blocking the exit from the Persian Gulf would be a difficult task for any Middle Eastern military: An attacker would need to routinely hit and disable approximately 10 oil tankers each day, requiring multiple successful strikes per ship, firing roughly 50 missiles per day. The attacker would have to keep its forces alive and operational in the face of defenders’ efforts to prevent the attacks. Iran is the state that has threatened to close the Strait, yet it lacks the military capacity necessary to do so. Perhaps the greatest contribution that the United States could make to the continuing safe transit of oil through the Strait of Hormuz is to step back from the brink of conflict with Iran.

Russia and China aren’t so foolish as to repeat our mistakes

Despite alarmism about the possibility of Russia or China making a bid for regional hegemony in the Middle East, neither has undertaken a concerted effort to do so. Russia’s presence in Syria is long-standing, and in general, Russia appears motivated to expand its role as a regional mediator; China is primarily interested in expanding its economic ties to the region. Both have observed U.S. military misadventures in the region, and neither appears eager to repeat America’s mistakes. Most importantly, neither has the capability to overcome the obstacles that made U.S. military operations in the region so difficult and costly — nor to potentially achieve a more expansive aim than the United States ever tried to achieve, namely establishing regional hegemony.

Fewer arms sales would help sustain the existing multipolar balance

To help protect the existing multipolar balance of power in the region, the United States should reduce arms sales, or at least prioritize the sale of defensive capacities, and offer strategic intelligence to all regional players, so any potential troop build up will be known in advance. If the United States needed to fight a war, it has the air and naval power to do so without peacetime presence or operations on the ground.

With our interests safe, Americans can return home

Given the extreme difficulties faced either by a would-be regional hegemon or an attempt to close the Strait of Hormuz, the United States has no compelling military need to keep a permanent troop presence in the Middle East. It should be the medium- to long-term objective of the United States to align its military presence with its strategic interests in the Middle East, beginning a responsible and timely drawdown of U.S. forces in the region now.

Introduction

Why is it so difficult for the United States to bring its troops home from the Middle East? Three successive American Presidents — Barack Obama, Donald Trump, and Joe Biden — have pledged to end the post 9/11 wars and reunite U.S. soldiers with their families. Yet, fulfilling that pledge has proven tougher than expected. Do U.S. interests in the region require so much of the U.S. military that full-scale withdrawals are not feasible? Alternatively, do other factors, such as political and economic interests, inertia, or objections by strategic partners, prevent the United States from pursuing its first-order security interests? These questions have become all the more timely and important in light of a global review of American force posture announced by Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin in February 2021.1

This paper argues that the United States has no compelling military need to keep a permanent troop presence in the Middle East. The two core U.S. interests in the region — preventing a hostile hegemon and ensuring the free flow of oil through the Strait of Hormuz — can be achieved without a permanent military presence. There are no plausible paths for an adversary, regional or extra-regional, to achieve a situation that would harm these core U.S. interests. No country can plausibly establish hegemony in the Middle East, nor can a regional power close the Strait of Hormuz and strangle the flow of oil. To the extent that the United States might need to intervene militarily, it would not need a permanent military presence in the region to do so.

While a full military withdrawal from the region is possible on military grounds, political and other factors render it infeasible in the short run. However, it should be the medium to long-term objective of the United States to align its military presence with its strategic interests in the Middle East by beginning a responsible and timely drawdown of U.S. forces in the region.

Why the current U.S. presence is militarily unnecessary

True U.S. interests in this region, as in any other region abroad, ultimately derive from the core national principles of preserving and advancing the security and well-being of the American people. In a previous Quincy Institute paper, Paul Pillar, Andrew Bacevich, Annelle Sheline, and Trita Parsi argued that U.S. objectives in the Middle East — the region-specific interests that make the ultimate U.S. goals concrete — are limited to preventing the emergence of a regional hegemon and helping to maintain the flow of global trade.2 This paper argues that neither warrants a major U.S. military presence in the Middle East, let alone American pursuit of regional military dominance.

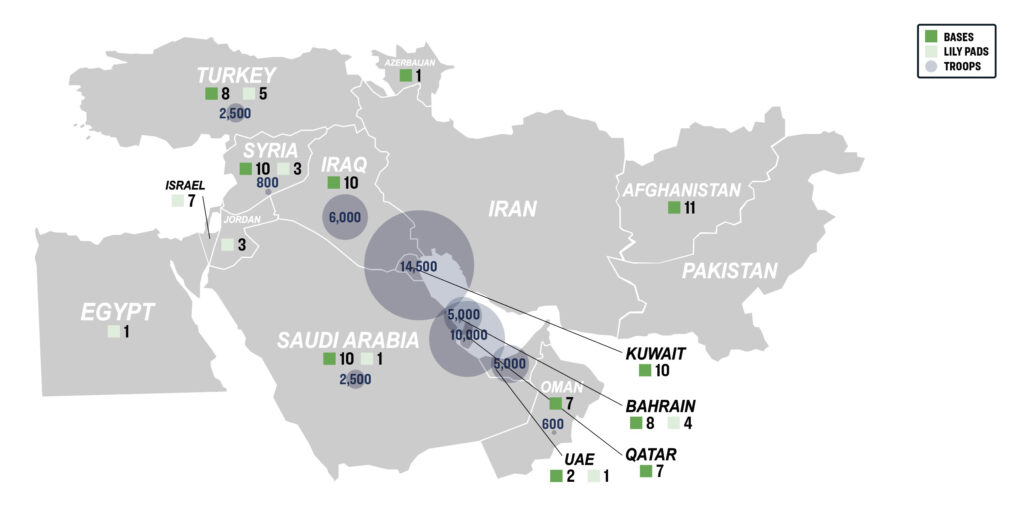

U.S. Military Installations in South and West Asia, 2020

Base: Greater than 10 acres in area or $10 million in value

Lily pad/Small base: Less than 10 acres in area or $10 million in value

U.S. Funded: U.S. personnel may have access to or use facilities paid for in part or fully by the U.S. taxpayers

The Washington foreign policy establishment tends to adopt an expansive definition of U.S. interests in the Middle East. Overreach in defining interests goes a long way in explaining America’s military overextension in the region. Nevertheless, even accepting a broad definition of U.S. interests would still not warrant a permanent U.S. military presence in the Middle East. This section briefly considers and rejects a range of additional potential U.S. interests in the Middle East, leaving the two core interests identified in the earlier Quincy Institute report as the ones that should be considered in determining U.S. military force posture and missions in the region.

Terrorism

The threat of terrorism is frequently invoked as a justification for the U.S. military to maintain a presence in countries from Afghanistan to Syria. Yet after twenty years of fighting a global war on terror (GWOT), the evidence is irrefutable: Militaries are ineffective at combating terrorism. Instead, preventing terrorism has significant parallels to preventing crime, in that it can never be fully eliminated but can be reduced through effective governance and policing activities. In contrast, the presence of a foreign military force consistently generates both grievances and acts of violence that inspire additional acts of terrorism. Foreign military occupation in particular makes the threat of terrorism more acute.

The presence of a foreign military force consistently generates both grievances and acts of violence that inspire additional acts of terrorism.

Instead of repeating the failed strategies that followed 9/11, the United States should focus on preventing any major act of foreign terrorism in domestic territory, something that it has successfully accomplished since 2001. The full elimination of all terrorist threats would require a level of state authoritarianism that Americans would find intolerable and anathema to their values; instead, the security establishment has successfully eliminated some threats and continues to monitor others. Finally, if U.S. leaders perceive the presence of a foreign terrorist threat, the U.S. military has demonstrated its ability to eliminate targets without a significant troop presence on the ground.

Israel

America’s security commitment to Israel is often mentioned to justify the presence of the U.S. military in the Middle East. Yet circumstances have shifted since Israel’s establishment, and decades of U.S. support and partnership have provided Israel with a robust capacity to defend itself, including with nuclear weapons. The U.S. project to empower Israel has been successful, and U.S. military defense of Israel need not drive American strategy in the Middle East. In fact, the instability that the U.S. military presence in the Middle East fuels may actually undermine Israel’s long-term security.

Nuclear non-proliferation

A third claim regarding the need for a persistent U.S. presence in the region is to enforce nuclear non-proliferation, often specifically in reference to Iran. The reasoning behind this claim was always flawed, as it arguably has been the ongoing U.S. military presence in the region that has driven Iran to feel it had no means of achieving security without acquiring nuclear deterrence. Moreover, the presence of U.S. troops has played no discernable role in dissuading Middle Eastern countries from acquiring nuclear weapons. It was not U.S. military strikes that undermined possible Syrian or Iraqi nuclear programs, and Egypt did not decide to discontinue its nuclear program because of a U.S. troop deployment.

Stability

Justifications for U.S. military presence in the Middle East sometimes emphasize stability as a core U.S. interest. In general, regional political stability is conducive to U.S. interests — a more stable Middle East is less likely to threaten the core interests of preventing a hegemonic takeover and protecting essential trade. Yet, there is little to suggest that a permanent U.S. troop presence is either necessary for stability or conducive to it. Indeed, the United States’ implicit security guarantees to regional partners have in many instances fueled their reckless and destabilizing behavior due to their perception that the United States will come to their aid if they get into trouble. The Saudi war in Yemen is a case in point.

Human rights

The protection of human rights is often used as a justification for U.S. military intervention, but there is no evidence to support the idea that a permanent troop presence in the Middle East deters human rights violations. On the contrary, mindful of the fact that many of America’s strategic partners in the region are some of the world’s most notorious human rights violators, it is more reasonable to conclude that the U.S. military presence in the region has served to protect these regimes despite their human rights violations. Moreover, when the United States has intervened militarily in order to prevent human rights abuses, the interventions themselves have generally caused massive human rights violations, as evidenced by the U.S. interventions in Iraq and Libya.

Military Requirements to Protect Core U.S. Interests

The Quincy Institute’s proposed strategy for the Middle East sets two goals for the U.S. military: preventing establishment of regional hegemony through military conquest and maintaining the flow of oil through the Strait of Hormuz to international markets. To decide what these goals ask the U.S. military to do — what forces to acquire, how to train and exercise, and where they should be positioned in peacetime to deter and, if necessary, respond to threats — requires answering a series of questions for each goal: What would it take for an adversary to bring about one of the undesirable conditions, assuming that an adversary desired to do so? Does any country in the Middle East have that capability, or is any country within near-term striking distance of having such capability? What actions would the U.S. military need to take to tip the balance of capabilities against such an adversary? And what force structure and posture would best prepare the U.S. military to thwart such an adversary, minimizing cost and risk and maximizing the visibility of the U.S. capability, thereby creating the conditions for credible deterrence?3

Preventing Regional Hegemony

Preventing regional hegemony means preventing a specific distribution of power and influence in a significant area. John Mearsheimer famously defines a hegemon as “a state that is so powerful that it dominates all the other states in the system,” whether applied at the global or regional level.4 For example, in a recent application of the concept to the potential for China’s rise in East Asia, Denny Roy defines regional hegemony as “the ability to compel the other governments in the region to conform to China’s preferences on political and strategic issues as well as to prevent or roll back any major strategic re-adjustment that China chooses to oppose.”5 Building the definition around compelling other states may seem limiting, because in some regions one country may have a substantial amount of “soft power” — that is, the ability to appeal to other countries such that they willingly agree to go along with the great power’s preferences — and that could make it possible for a country to achieve regional hegemony through the power of ideas rather than military force.6 But given the actual regional politics of the Middle East, dominated by bitter political, cultural, and religious rivalries, coercion is the route to regional hegemony that needs analysis.

A contender for regional hegemony would need the realistic ability to project power more than 1000 kilometers and to expand its borders by tens of thousands of square kilometers.

The lack of intra-Middle East trade and investment that could lead to meaningful economic coercion means that military power is the only plausible route to Middle Eastern regional hegemony, whether through actual conquest or the acknowledged ability to conquer that might lead some countries to accommodate the regional hegemon’s rise. While regional hegemony would not require the capability to conquer and hold the entire geographic area from North Africa to the Indian subcontinent and from Central Asia to the Indian Ocean, a large Middle Eastern state’s military defeat of a small neighbor would not create regional hegemony. A plausible working definition would require that one of four more substantial potential Middle Eastern powers — Iran, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, or Turkey — knock at least two of the others out of the Middle Eastern balance of power.7

That is a daunting political-military task, and its difficulty would greatly aid any U.S. effort to prevent regional hegemony in the Middle East. The tendency of local rivals not to willingly submit, the relatively high costs and risks of military offensives, and the need to transport military forces and supplies across long distances to conquer and occupy the politically relevant area all militate against the achievement of regional hegemony. Modern conventional military forces, which in principle offer the potential to move and communicate across the relevant distances, are expensive and difficult to create and maintain. In general, for offensive forces to have a good chance to win, they need to be significantly larger than the defending forces.8 And while modern warfare is difficult for both the offense and the defense, and incompetence can lead to withering casualties or rapid collapse for either side in a fight,9 inertia also favors the status quo. The offense is only likely to win if it enjoys an advantage in competence at executing difficult tactical and operational maneuvers; incompetence on both sides, competence on both sides, or a competence advantage for the defender are all likely to preserve independent political control of territory — that is, to prevent regional hegemony.

Moreover, the geography of the region does not make it easy to achieve hegemony. A contender would need the realistic ability to project power more than 1000 kilometers and to expand its borders by tens of thousands of square kilometers. For example, those distances would be required for one widely considered “hegemony risk:” Iranian conquest from Iran’s current border through Kuwait and southern Iraq into the oil-rich eastern province of Saudi Arabia and down the Persian Gulf coast to include the small monarchies in the southeastern part of the Arabian Peninsula. And while the terrain covered in such an advance does not offer many obvious defensive barriers to block a military advance, desert sand is not good ground for most modern military vehicles, channeling heavy transports onto a handful of roads, nor does it offer the aggressor much cover and concealment.10 In an alternative scenario, conquest of substantial parts of Iran by one of the other contenders would require not only advancing across much open space but also crossing major mountain ranges, channeling the attacking forces through particular passes that, while easier to move through than the heights of the mountains, would also offer substantial combat advantages to the defense.11 The offensive tasks for a potential hegemon to overcome the geography are not impossible, but they would be difficult.

A Middle Eastern army would need at least five core capabilities to potentially threaten to create regional hegemony. First, and most simply — not even considering opposing forces yet — the attacking army would need substantial logistics and maintenance capabilities. Keeping forces in the field supplied with food, fuel, munitions, and other consumables is a daunting task. The huge volumes needed would fill limited road networks with trucks, vulnerable to traffic jams, enemy air attack, and partisan ambush.12 The organizational task of determining which supplies are needed by which part of the army is itself complex, and normal mistakes can leave undersupplied units without matériel to move and fight or oversupplied units with clogged, unmanageable depots. Finally, beyond supplying frontline units, militaries have to keep their equipment running. Trucks, armored personnel carriers, artillery pieces, and tanks all break down; when under their own power (as opposed to carried on a train or heavy-equipment transport truck), even tanks that are up-to-date on routine maintenance might expect a mean time between failures of a couple of days of combat use, and combat aircraft are even more maintenance-intensive.13 Only forces that are good at maintenance can sustain major offensive military campaigns for long.

The United States is used to air supremacy in its wars, where no enemy aircraft even attempt to fly, let alone attack U.S. ground forces. No Middle Eastern combatant can reasonably expect that luxury.

Middle Eastern militaries have sometimes managed amazing logistical feats. For example, the Iraqi military, using supply lines through its home territory, was almost never short of supplies on either the offense or the defense during the Iran-Iraq War.14 But the combination of lack of prepared infrastructure and unfamiliarity with the local route network make it especially hard to supply conquering forces. The most capable historical case in the region is probably the Libyan army, which sometimes projected power far into Chad and even used air bridges to supply forward forces, but that kind of mobility is the exception, and no one should assume that every attacking army can manage and sustain it.15 Overall, the maintenance record of Middle Eastern armed forces is generally poor. By cannibalizing some of its inventory for spare parts and applying some ingenuity, the Iranian military has famously kept functional some very old American equipment, dating to the Shah’s era, but that is the result of a lot of effort on a limited scale.16 Other Middle Eastern armies have failed the test of maintenance repeatedly, especially the sort of field maintenance conducted by fighting forces near the front that keeps equipment in the fight under less-than-ideal circumstances.17 Instead, regional armies tend to rely on depot-level maintenance for even routine tasks, which slows everything down, makes it all more expensive, adds to the logistical burden of traffic going to and from the front, and leaves field forces exposed for extended periods of time without the key equipment needed to fight modern battles.

Second, the aggressor’s army would need to be able to protect itself while on the move, notably with high quality, mobile air defenses. The United States is used to air supremacy in its wars, where no enemy aircraft even attempt to fly, let alone attack U.S. ground forces. No Middle Eastern combatant can reasonably expect that luxury. The penalty for leaving ground forces vulnerable to air attack is substantial: It is worth remembering what was described as a “turkey shoot” on the “highway of death” as Iraqi forces tried to withdraw from Kuwait in the 1991 Gulf War, or the earlier battle of Khafji in that same war where air power essentially stopped an Iraqi attack in its tracks.18 Moving ground forces are relatively easy to see from the air, and motion and the mass of an army on the offense, trying to take and hold territory, help separate real military equipment from decoys.19 Modern air-to-ground munitions can then minimize the difficulty for pilots (or weapon system officers in two-seater tactical aircraft) targeting the slow-moving ground vehicles.20 Even air forces that have struggled to discriminate military targets and hit what they are aiming for in the midst of cover and concealment, such as Saudi air forces operating in Yemen, should have an easier time against large military formations on the move through the desert in a hypothetical bid for regional hegemony in the Middle East.

Ground-based air defenses can disrupt that vulnerability, keeping enemy aircraft away from ground troops or scaring pilots into maneuvers that make even sophisticated precision weapons miss, even if the air defenses don’t shoot down the attack planes.21 But many potential Middle Eastern combatants have modern air-to-ground weapons that can be targeted and launched from above the range of ground-based mobile air defense artillery, meaning that those trying to cover a ground advance need to rely on sophisticated surface-to-air missile systems (SAMs) that few Middle Eastern militaries have. Furthermore, modern SAMs are expensive, finicky, and require careful coordination with ground forces to give the air defenders time to set up their radars, maintain their coverage while ground forces move through the engagement envelope protected from enemy aircraft, and then wait for another air-defense battery to leap-frog forward to protect the next phase of the army’s ground advance. Such offensive combined-arms maneuvers take substantial skill and practice — hardly a simple matter of buying Russian S-400s (if the Russians are willing to sell them) and flipping a few switches.22

Third, the potential hegemon’s army would need to be able to react to unforeseen circumstances.23 Attackers can plan offensives meticulously, and even relatively low-skill military forces can execute pre-planned maneuvers that they have practiced in advance. However, as Helmuth von Moltke’s famous aphorism is often translated, “no plan survives first contact with the enemy.”24 As campaign plans become bigger and more complex and extend over greater distances and time scales, as occurs during attempts to conquer substantial swaths of territory, the actual situation faced by troops on the battlefield deviates further and further from the script. High-quality troops with gifted leaders — those who are willing and able to take the initiative, adapt to the new situation, and communicate changes in the plan to remain coordinated with other units — can maintain an offensive in the face of unforeseen events. But most offensives bog down as troops get lost, slow down due to adverse weather or road conditions, or run into enemy troops who have maneuvered or deployed in unexpected ways.

Only a few militaries manage the level of military effectiveness needed for a major offensive — that is, effectiveness that can be sustained for a long campaign with significant casualties.

Historically, Middle Eastern militaries have been plagued by leadership and adaptation failures at all levels of command, from small units refusing to deviate from the original plan without explicit orders from above to theater-wide leaders’ failure to recognize and react to battlefield reality.25 These problems are not essential characteristics of all regional armed forces, but their political and cultural roots are likely to remain common for the foreseeable future. Even if a few elite units are groomed for high performance or happen to perform well through the luck of the draw in getting better leadership, regional militaries as a whole are likely to be held back by the morass of slow-reacting, mediocre units on whose performance a bid for hegemony would have to rely.

Fourth, the aggressor would need to be good at fighting on the offense under modern battlefield conditions.26 The modern battlefield is witheringly lethal.27 Dismounted infantry and heavy armored vehicles alike are at risk. Troops can only survive through complex, coordinated activities. Soldiers need to maneuver in short bursts from one terrain feature to another to maintain concealment from enemy fire — features that individual soldiers need to be able to identify under highly stressful conditions. Soldiers also need to limit their maneuvers to only those times when they are covered by friendly forces firing to suppress the enemy’s ability to observe and respond. Individual soldiers and small-unit leaders need to recognize the different types of threats that they face and be able to communicate with and rely on the right type of friendly forces to suppress the enemy’s fire. Even troops away from the battlefront are vulnerable: When artillery fires, it often reveals its location to the enemy and becomes subject to counter-battery fire; when air defense units turn on their radars, their emissions reveal their location, and it is only a matter of time before adversary munitions home in, forcing the unit to move, seek cover, or at least turn off its radar, taking it out of the fight. All units need to know how to shoot, scoot, cover, and communicate.28 Military effectiveness, or even just survival, takes much more than courage, physical strength, and basic marksmanship. Only a few militaries manage the level of military effectiveness needed for a major offensive — that is, effectiveness that can be sustained for a long campaign with significant casualties.

Fifth, even after a conventional victory, a potential hegemon’s army would need to maintain political control of occupied territory, converting the gains of conquest into political hegemony, governing and exploiting the resources of the defeated states.29 In the modern age of nationalism, most conquering armies can expect resistance. When the conqueror comes from a different ethnicity or religious background, the probability of local resistance is higher, and the resistors may be especially willing to suffer and sacrifice to fight back fiercely.30 In recent decades, insurgencies have been ubiquitous in the Middle East, resisting extra-regional and intra-regional occupiers alike. Foreign occupiers may struggle to fight back and impose order. They may be unfamiliar with local customs, habits, and even languages, limiting their intelligence collection and understanding of what reactions and defenses could make the situation worse rather than better.31 Furthermore, in the Middle East, the occupier’s ability to provide good governance may be limited even at home, let alone in the occupied territory, reducing the occupier’s ability to co-opt local civilians to aid in controlling an insurgency.32 And patrolling occupied territory requires large numbers of troops, diverting soldiers from the next planned offensive in the bid for hegemony.33 Overall, making conquest cumulative — making initial gains an asset rather than a liability in the continuing effort to establish regional hegemony — can be very difficult.

None of the four potential contenders in the Middle East has the requisite capabilities to establish hegemony.

A potential regional hegemon would need all five of these core capabilities. None of the four potential contenders in the Middle East has the requisite capabilities, and none has the plausible potential to rapidly acquire them in a way that would give it a relative advantage over its opponents.

As of today, Iraq looks to be the weakest potential contender. Its military is broken after decades of unsuccessful combat. What is left of the Iraqi military is almost entirely focused on internal defense, fighting with and against militias struggling for local political influence and trying to suppress terrorism.34 The military has been politicized, and many of its members are corrupt, both factors that substantially reduce the effectiveness of its leadership, initiative, and unit cohesion.35 Logistics no longer function, partly due to corruption that leads supplies to disappear or to be misallocated, but also due to failures of the army’s transition to a complex, computer-based, “modern” system that attempts to maximize efficiency but relies too much on individual initiative (units requesting what they need) and is too brittle for local conditions.36 And finally, Iraq’s total population is probably too small to conquer and occupy its major neighbors, especially given the high-salience internal divisions within Iraq that would make it hard to draw from the full population base for an offensive war. It might be more reasonable to fear that Iraq would not put up the expected resistance to another country’s bid for hegemony than to fear that Iraq itself would become a potential hegemon. On the plus side, Iraq has a history of nationalism bringing the country’s population together to resist an outside invader, though that Iran-Iraq War history was a long time ago, before the heightening of internal divisions (and heightened allegiance of local militias to Iranian support) during the long Iraqi civil war.

Saudi Arabia likewise is an unlikely contender for regional hegemony. Access to money is Saudi Arabia’s greatest advantage — notably, money to buy advanced weapons and perhaps allies, whether other governments or local militias within other countries. But Saudi money is not boundless, and more and more seems committed to ensuring internal stability, leaving less surplus to fund military adventures.37 More importantly, Saudi military disadvantages are substantial and cannot be overcome simply through spending. Saudi Arabia’s population is even smaller than Iraq’s, and the regime fears that a significant fraction is not politically or religiously reliable, limiting its ability to mobilize for an offensive. Saudi Arabia would be hard pressed to create the military mass to attack and occupy its neighbors. Mercenaries and bribed local militias would not be sufficient to serve as an occupying force. Furthermore, the Saudi armed forces have performed poorly in military exercises and past conflicts, notably in Yemen, and they would require an enormous transformation to prepare for major offensive operations.38 Basic marksmanship is weak; few pilots and soldiers are able to use the full range of capabilities of their high-tech equipment. Maintenance is often neglected and is slowly conducted at the depot rather than in the field, often by foreign contractors who might be induced (say, by the United States) to leave rather than support a Saudi offensive war. Saudi units do not work together to maximize combined-arms effects. The Saudi military is not equipped with mobile air defense or with the necessary logistics equipment to supply power-projection forces. Finally, the Saudis have political and religious conflicts with many people across the Middle East — in recent years, with Qatar, Egypt, various factions in Lebanon, Syria, Yemen, Bahrain, Iraq, and of course Iran — so interactions with locals in conquered countries would likely prove extremely difficult.39

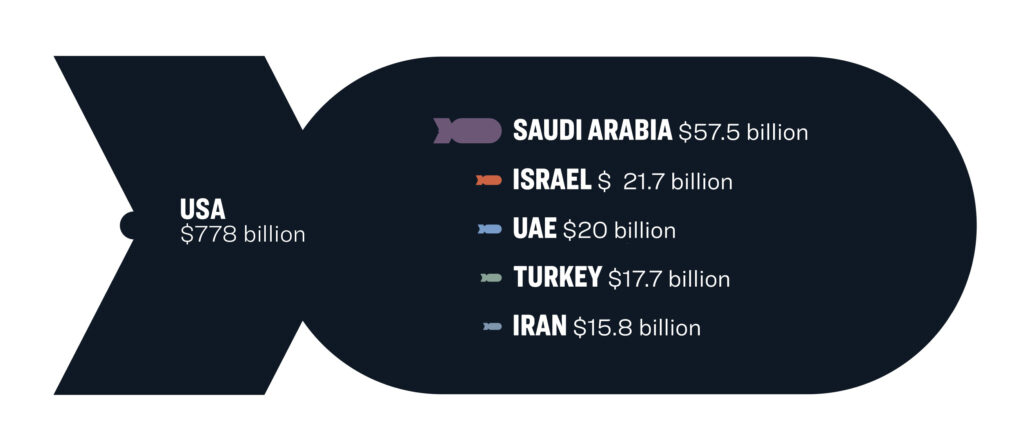

Comparison of Military Expenditure in 2020

SIPRI does not have data for Qatar and UAE, which are calculated separately using the CIA World Factbook and the 2017 estimate.

Iran is the country that Americans most often think of as posing a threat to dominate the Middle East, but its military lacks key capabilities to make a hegemonic bid. The most important feature of the Iranian military is its emphasis on unconventional warfare, especially in the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, essentially a second military force that receives more resources than Iran’s traditional military.40 Some of the unconventional warfare techniques are more public relations sizzle than real military capabilities: photo ops of fast speedboats circling and volley fires of modestly accurate ballistic missiles — or photoshopped facsimiles of such spectacles.41 Yet other special warfare capabilities are real, if limited, allowing the IRGC and the Quds Force to meaningfully support allies in various Middle Eastern civil wars and to help the Iranian regime maintain political stability at home.42 These capabilities might make Iran relatively well placed to handle some of the requirements of post-conquest occupations, although Iran’s Persian and Shi’a characteristics would simultaneously exacerbate the difficulty of interactions with many conquered locals. But experience in internal politics also comes with other disadvantages. Advancement to military leadership positions in Iran can depend significantly on politicking and religious loyalty rather than on merit, and some military leaders actually spend substantial effort on running the various businesses that the military owns, which account for a significant fraction of the Iranian economy — rarely, if ever, a feature of first-class offensive potential.43 Iran’s best military forces are neither trained nor equipped to defeat rival militaries and seize control of territory.

Meanwhile, Iran’s conventional military has struggled for decades. In some ways, it is impressive that Iran has managed to keep any of its equipment operating through intense economic sanctions that include spare parts embargoes and export controls on military and dual-use products. But maintenance, upgrades, and even the ability to minimally equip a large force are still problems for Iran. When the domestic Iranian arms industry announces a new, innovative piece of equipment, it is often cobbling together working bits of old equipment to produce a chimera that at least keeps some tanks or helicopters in the field; production volumes are necessarily limited.44 Even if diplomatic circumstances change, allowing Iran to purchase some of the modern equipment that it would need for major offensives, it would need to assimilate the new equipment, learn to use it to its full potential, and overcome profound internal barriers that have limited the Iranian military’s ability to pull off combined-arms operations in the past.45 For example, Iran has for years supposedly been about to take delivery of advanced Russian S-400 mobile air defense systems, but even if it does, the Iranian military will need to learn to use them, in a combined arms fashion, in the difficult circumstances of moving for military offensives.46 Iran’s leadership would also always be tempted to reserve the advanced air defenses for high-value targets at home, notably political leadership and nuclear facilities. And even if Iran’s policy changed and it made a major commitment to investing in its conventional forces, the organizational division between the IRGC and the conventional military would continue to severely hamper strategic planning and operational effectiveness.47 Turning Iran’s military into an offensive force capable of threatening to establish regional hegemony would be a major, expensive, politically wrenching, long-term project.

Finally, Turkey is actually the closest regional power to having the capability to threaten regional hegemony. The main disadvantages that the Turks would face are the huge distances that its military would have to cover to defeat the other substantial militaries in the region and the problems that the Turkish military would likely face interacting with the local population wherever it fights in the Middle East. Turks would face ethnic, religious, and cultural differences fighting in key parts of the region; Turkey would be especially likely to stimulate resistance to an invasion or occupation force. On the other hand, Turkey has a large population and a large, modern military. The army’s training and equipment have benefitted from NATO membership, and its conventional combat experience has been relatively successful.48 Yet these strengths must match up against compensating weaknesses. Some of Turkey’s most important military activities have focused on internal, unconventional operations, whether against its domestic Kurdish population or across the border in Syria, and complicated internal politics and a history of coups have led to debilitating politicization and coup-proofing within the military.49 Those factors would hamper Turkish offensive capabilities in the Middle East.

Overall, the Middle East is generally a region of low-competence conventional militaries. The local militaries are politicized and significantly, though not exclusively, oriented toward ensuring domestic control in their home countries. That is good for the United States, which desires to prevent regional hegemony.50 Wars between ineffective large militaries, like the Iran-Iraq War of the 1980s, can cause terrible suffering, but they have little effect on the U.S. national interest. Offensives gain little ground at tremendous cost, and the slow activity at the front offers other countries in the region many opportunities to adjust their support for one side or the other to maintain balance.

Overall, the Middle East is generally a region of low-competence conventional militaries.

Moreover, some of the smaller countries in the Middle East seem to have the higher quality militaries. “Little Sparta,” as the United Arab Emirates is sometimes known, can meaningfully contribute to defense against a marauding regional power, but the tiny UAE cannot realistically threaten to sweep through several larger countries in a bid for hegemony. The same goes for the relatively combat-effective Hezbollah fighters in Lebanon and for Israel’s vaunted military.51 Small militaries that punch above their weight are also good for the status quo-oriented United States.

Some fear the possibility of an extra-regional power establishing hegemony in the Middle East — notably, that a great power like China or Russia would ally with a country within the region, build military bases, and flow enough military power into the Middle East to dominate it. The challenges that the United States has faced trying to control events in the Middle East in recent decades should create substantial skepticism that another foreign military power with much weaker and less experienced power-projection forces than the United States could create a regional military hegemony, a more difficult mission than the United States’ unsuccessful effort. Furthermore, China and Russia have much less air and sealift capacity to support such an expedition, and neither enjoys the “Command of the Commons” that facilitates such power projection.52 Finally, despite Russia’s military ties to Syria and the much-debated possibility of a growing Chinese-Iranian relationship, there is little indication that a major Middle Eastern power is interested in forging an offensive military alliance with either extra-regional power.53 Such an alliance, if backed by real military capabilities and deployments of the hundreds of thousands of foreign troops that would be needed to bid for regional hegemony, would present a major change to the international security environment that would require significant rethinking of U.S. national security policy. But that potential could not evolve rapidly, and without the threat of a sudden shift in dynamics, there is no reason for pre-commitments or preventive responses. The United States (and other countries around the world) could consider such a situation if and when it started to evolve, developing a new strategy for that possible future scenario as its contours became clear. For now, the threat of an extra-regional Middle Eastern hegemon — whether Russia or China — is negligible in any reasonable military analysis of the region.

Given the low risk of regional hegemony in the Middle East, what might the United States military nevertheless do to serve the U.S. national interest? First, the United States might reasonably choose to cut back on its current tool of choice in the region. For decades, much of the non-combat U.S. effort has emphasized attempts to train local forces that the United States has considered to be “friendly.” These efforts have had little payoff in terms of apparent improvements in local force quality.54 Notably, heavily trained Iraqi forces melted away in the face of ISIS attacks, and U.S.-trained Saudi forces performed poorly in Yemen, struggling against Houthi militias while killing and injuring many non-combatants. Perhaps more important, even successful training, if it were to improve Middle Eastern militaries’ ability to execute modern combined arms tactics, would augment the locals’ capabilities on both the offensive and the defensive, offering little leverage over the core issue for the U.S. national interest, namely locals’ ability to bid for regional hegemony. Reducing U.S. military contact with regional militaries could also improve the U.S. image among the people of the Middle East — or at least mitigate the conspiratorial image that the United States is the real power controlling local politics and setting the local agenda. Even those people inclined to be hostile to the United States would tend to view the U.S. military as a more distant influence rather than as a day-to-day priority on their list of complaints.55

If the United States found it necessary to fight a war in the Middle East — if, against the odds, a regional power actually seemed on the march towards regional hegemony — the U.S. military’s primary tool to tip the balance would be air power.

Second, even if the United States opted not to cut back its arms sales to the region, it could change the emphasis in the types of weapons that it sells. Even though it is rarely possible to classify particular weapon systems as “favoring the offense” or “favoring the defense” — because supposedly defensive weapons can be employed to lightly screen a front while freeing up other forces for an attack and because supposedly offensive weapons can be employed in counterattacks to blunt an opponent’s thrust — the United States could focus its arms sales on weapons that generally make it harder for armies to move in open territory.56 That choice could hamper both the offensive and the defensive in the region, but it would hamper the offensive to a relatively greater extent. Modern anti-tank guided missiles, even those operated by dismounted infantry, can stop advancing forces or at least raise the opponent’s need to use combined-arms techniques to suppress the defenders’ fire — putting more emphasis on a difficult-to-perform military task that regional militaries have shown little ability to execute in the past. Small unmanned aerial systems (drones) likewise can help defenders find and damage attackers who are on the move without offering as much benefit on the offense because of their range and payload limitations.57 The focus should be on relatively simple, low-cost, easy-to-operate systems that put additional stress on offensive forces and make life easier for defenders.

Third, and perhaps most important, the United States could offer stand-off, strategic intelligence to everyone in the region that would make successful conventional offensives difficult or even impossible. Most obviously, U.S. satellite reconnaissance could alert the world, including local defenders, to an imminent threat of troops massing on a Middle Eastern border, minimizing the risk that any offensive effort would achieve strategic surprise. Truthfully, that sort of alert would not require the sophistication of U.S. intelligence satellites, and the United States would not need to risk revealing its true high-end satellite capabilities in transmitting this sort of intelligence. Everyone in the world now has commercial access to satellite imagery adequate for this purpose. Open-source global news should be sufficient to prevent sudden military surprise, whether Middle Eastern governments are themselves purchasing satellite images or not.58

What specifically U.S. satellite-based intelligence could reveal that would be more useful and perhaps more decisive is evidence of Middle Eastern military exercises preparing for less-imminent offensives. Successful attacks by Middle Eastern militaries using modern military technology have been heavily scripted and practiced affairs — for example, the successful Iraqi offensives that ended the Iran-Iraq War in 1988 and that conquered Kuwait in 1990.59 Militaries can partially compensate for their officers’ lack of initiative and adaptability through extensive advance preparation, but if likely defenders are watching and learning the scripts, they can counter or blunt the coming offensives. The U.S. military might be uniquely positioned to monitor, understand, and explain offensive military preparations, certainly compared to the limited surveillance and analysis capabilities indigenous to the region. The commitment to do so — if the United States could build enough credibility for truthful intelligence assistance with countries in the region — could make a significant difference in blocking efforts to achieve regional hegemony. Given its past hostility toward certain countries in the region and the likely difficulty of building trusted intelligence-sharing relationships, the United States might even want to commit to revealing evidence of offensive preparation by Middle Eastern militaries publicly rather than privately as a way to build U.S. credibility with all countries in the region.

The political benefits of staying offshore and avoiding the need to choose friends and allies in peacetime, long in advance of any major conventional war in the Middle East, would be substantial.

And finally, if the United States found it necessary to fight a war in the Middle East — if, against the odds, a regional power actually seemed on the march towards regional hegemony — the U.S. military’s primary tool to tip the balance would be air power. Regional armies on the offensive would be terribly exposed, moving along known and constrained routes, often in the open, and with weak mobile air defenses. These conventional forces would be easy pickings for American air-launched precision-guided munitions, munitions that can readily be employed from carrier-based aircraft. While land-based aircraft have an advantage in their sortie-generation rate, which could prove decisive in an intense campaign against a large, effective, peer-competitor military in some terrain, the actual conditions of a Middle Eastern defense would be very unlikely to require the maximum U.S. effort that local air bases would enable. Even a major offensive by a Middle Eastern military would not involve so many vehicles and such a rapid rate of advance as to overwhelm sea-based air power’s striking potential. Furthermore, a relatively small number of hits on forces advancing while confined to a narrow channel like a road or a pass (as in a Middle Eastern bid for hegemony) can create panic and traffic jams that would halt the advance and give time for “slow” sea-based air power to launch plenty of sorties to eliminate the threat. Finally, in real (and very unlikely) extremis, land-based U.S. aircraft could fly to and use local air bases, as the United States planned in the 1980s and executed in the 1991 Gulf War. Primarily relying on carrier-based air power for the ultimate fallback intervention force might be a bit more expensive in terms of the defense budget cost of building and maintaining aircraft carriers and carrier-based aircraft compared to the defense budget cost of land-based tactical aircraft. But the political benefits of staying offshore and avoiding the need to choose friends and allies in peacetime, long in advance of any major conventional war in the Middle East, would be substantial.

Kenneth Pollack, a leading analyst of Middle Eastern militaries, offered an interesting summary of the political-military development of the Arab states over the past century: They are slowly learning that they cannot achieve their offensive political goals using military force, given the current balance of power and military technology.60 The same point extends to non-Arab states in the region, including Iran. It may be that some countries have not yet gotten that message — for example, Saudi Arabia continues futilely and brutally to try to assert its military power in Yemen — but the underlying fact is that attempts at conquest and offensive power projection in the region are not productive. That leaves the United States military with nothing much to do in its effort to prevent the rise of a Middle Eastern regional hegemon.

Protecting the Flow of Oil Through the Strait of Hormuz

The other major goal set by the Quincy Institute’s Middle East strategy is to preserve the free flow of oil through the Strait of Hormuz.61 According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, an average of 20.7 million barrels of crude oil and petroleum products traveled from Persian Gulf ports through the strait each day to reach global markets in 2018.62 Flows through the strait vary somewhat over time — for example, their points of origin and total amount changed as the level of stringency of economic sanctions against Iranian oil exports varied over the past decade — but they have remained in the neighborhood of satisfying 20 percent of global oil demand for many years.

It is impossible for military action to prevent attacks on a handful of ships at a time, but in recent years, the oil market has dealt with such small-scale attacks with barely a ripple.

It is impossible for military action to prevent attacks on a handful of ships at a time, but in recent years, the oil market has dealt with such small-scale attacks with barely a ripple. Tankers have been hit with rocket-propelled grenades, missiles, limpet mines, and remotely controlled exploding speedboats, in some cases disrupting individual transits through the strait, and in some cases not.63 These events surely caused anxiety for seamen on the ships that were hit, though there is little indication of casualties from the attacks. They were surely costly for particular businesses, including the owners of the ships that were hit, their insurance companies that had to pay for repairs, and their customers who may have faced an unexpected delivery delay. But they did not have any effect at the scale of the immense global economy, in which many mechanisms naturally compensate for minor shifts in supply and demand.

Non-military disruptions of one or two tanker transits at a time are normal events, due to severe weather, accidents and unexpected maintenance issues, or surprising shifts in demand that cause traders to buy and sell oil during a tanker’s transit, changing the ship’s efficient route to market.64 Privately held oil inventories, which include billions of barrels of oil on any given day, accommodate these schedule variations naturally, and they do the same for the minor hiccups caused by small-scale attacks on oil trade.65 The inability of defending militaries to prevent such attacks does not justify a reinvigorated or expanded defensive military effort. Such small-scale attacks are rare because they have little effect and therefore do not motivate attackers to attempt them. Those that do occur are criminal-scale activities, a little friction in global markets best dealt with by coast guards and police work.

But were some country’s military to make a major effort that successfully blocked the full normal flow through the Strait of Hormuz, other sources of oil would not be able to compensate fully, even if governments triggered extreme compensation measures. The daily flow rate for oil from public stockpiles like the U.S. Strategic Petroleum Reserve is limited, pipelines that could divert oil to meet tankers on the Red Sea or Gulf of Oman rather than in the Persian Gulf can only accommodate a fraction of the exports that normally pass through the strait, and much of the world’s spare capacity for oil production is located behind the strait and would be cut off from markets by a transit disruption there.66 These major supply-side adjustment mechanisms could match, barrel for barrel, a disruption of roughly half of the oil that tankers normally carry through the Strait of Hormuz, at a relatively small increase in cost, as they have matched historic political-military disruptions of oil markets like the onset of the Libyan civil war.67 But a complete blockage of the strait would suddenly leave the market short on the order of 10 million barrels per day.68 And demand for oil is generally quite inelastic in the near term, meaning that the global economic cost of dealing with that shortage would be extremely traumatic, enough to call for a military response.69

Fortunately, military analysis shows that completely plugging the normal exit from the Persian Gulf would be a difficult task for any Middle Eastern military.70 Many studies simply skim over the analysis of how an attacker would pull off in practice what would be needed to “close the Strait of Hormuz,” making it seem like a dangerously imminent threat. But to deny the market that 10 million barrels per day, an attacker would need to routinely hit many targets while conducting complex offensive operations. It would need to identify the right targets to fire at, distinguishing valuable oil tankers from the many other ships that ply the strait’s waters. It would have to use multiple munitions per target ship to cause sufficient damage to stop the ship’s transit, despite the scarcity of those munitions. And it would have to properly operate the sophisticated munitions needed for the attacks, assuming that routine maintenance had kept those munitions in “fighting shape.” Finally, the attacker would have to take complicated steps to keep its forces alive and operational in the face of even local defenders’ efforts to prevent the attacks. Each of these steps is likely to prove challenging, especially given the less-than-perfect effectiveness that we have seen in the history of Middle Eastern military operations.71

In reality, only one Middle Eastern country poses any threat to seaborne oil flows in the Persian Gulf for the present and foreseeable future: Iran. No other state has procured an arsenal of anti-ship cruise missiles, sea mines, or heavy-weight torpedoes and their delivery systems, and no other state has created a large contingent of supposedly fanatical special forces allegedly ready to launch suicide attacks against ships.72 At the same time, Iranian leaders have regularly proclaimed their intent to attack oil tankers under certain conditions, especially as threatened retaliation against U.S. military action or even as a reaction to too-stringent economic sanctions against Iran.73 Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps conducts highly visible exercises, firing missiles (generally at mock targets) and sending swarms of patrol boats into the strait — political theater, good for YouTube viewers, to demonstrate the seriousness and credibility of Iran’s threats.74 But such razzle-dazzle is not the same thing as serious military exercises to prepare for the real-world complexity of a sustained campaign against Persian Gulf shipping.

The United States should recognize that an effort to disrupt oil flows through the Strait of Hormuz faces enormous challenges even without any U.S. reaction.

To carry all of the oil that normally flows through the strait, 33 tankers of varying sizes now exit the strait on an average day.75 The most valuable potential targets are the Very Large Crude Carriers (VLCCs) that carry some two million barrels of oil, and an average of at least 10 VLCCs exit the strait each day (and 10 could carry the typical oil exports through the strait).76 That is a large number of targets for an attacker to hit. And hitting tankers on one day would not permanently stop the flow of oil.77 Moreover, the strait is not so shallow that it could be blocked by a few sunken ships in the channel, as the Suez Canal was fifty years ago.78 If an attacker were to hit some tankers on one day, different tankers could attempt the passage on the next — and they likely would, because oil’s extreme value gives producers and shippers a strong motivation to adapt to new conditions, to repair damage rapidly, and to take risks to keep oil flowing to markets. Oil exporters could even offer to absorb the costs of higher insurance premiums, as they did during the Iran-Iraq War, since after all they are selling oil for prices far above the marginal cost of production.79 Frequent references to a potential doubling of tanker insurance rates are designed to sound scary, but the increase is relative to such a low baseline price as to amount to only pennies of extra cost per barrel of oil, when the price is amortized across the large volumes flowing through the strait. The profits for oil exporters would still be huge, which would keep ships sailing. And it would mean that the attacker would need to succeed in hitting many targets every day, day after day, to maintain a disruption to traffic through the strait.

The 1980s Tanker War provides a glimpse into oil tanker operators’ crisis behavior in the Persian Gulf. Tankers continued to sail through most of the conflict, despite the threat of attacks. So many sailed that the total number of ships attacked accounted for no more than 2 percent of the ships passing through the Gulf.80 The United States Navy ended up escorting convoys of reflagged Kuwaiti tankers at the end of the war, but the convoys did not start because they were the only way to get tankers through the gauntlet of attacks. Rather, the convoys were actually triggered by the dynamics of the Cold War, with the United States responding to the possibility that the Soviets might escort tankers.81 Today, one might imagine a similar diplomatic competition with the Chinese, but there is little military or economic reason to expect attacks on oil tankers to stop efforts to bring Persian Gulf oil exports to the global market.

Finding the roughly 10 targets a day that Iran would need to hit would also present a problem.82 Iran would likely “waste” some of its shots by mistakenly firing at less-valuable targets than oil tankers. The oil-carrying targets sail in the midst of dozens of other large ships each day, some of which are difficult to distinguish from tankers at a distance on the water, especially when long-range visibility is inhibited by the normally dusty, hazy, hot conditions of the Persian Gulf.83 And the strait is not so narrow (like Suez) that ships must travel through it single file, or in any identifiable pattern that would make it easier for the Iranian spotters and targeteers: at its narrowest, it is 39 kilometers (21 nautical miles) across. Even though peacetime traffic is organized to reduce the risk of accidents into the two relatively narrow channels of a Traffic Separation Scheme, the reality is that even heavily laden supertankers that need deep water have at least a twenty-mile width of “good water” to sail through the strait.84 VLCCs are indeed huge ships, but in wartime, they have many routes available into and out of the Persian Gulf, as they demonstrated when under threat during the long Iran-Iraq War.

The 1980s Tanker War provides a glimpse into oil tanker operators’ crisis behavior in the Persian Gulf. Tankers continued to sail through most of the conflict, despite the threat of attacks.

Scattering tankers from the normal peacetime routes might marginally increase accident risks, as the hard-to-maneuver behemoths sailed into waters filled with thousands of fishing dhows and reduced their coordination with other large, hard-to-maneuver commercial ships. That would increase the tankers’ insurance cost. Deviating from peacetime routes would also likely lengthen tankers’ transit routes through the strait, which would increase their fuel and carrying costs, though not as a significant fraction of the cost of a transit to East Asia, Europe, or India. On the other hand, scattering the tanker traffic would substantially complicate an attacker’s task in finding targets for anti-ship cruise missiles. And even if Iranian spotters correctly identified an oil-tanker target, a missile’s automatic terminal guidance, which homes in on the strongest radar reflection in its vicinity when it turns on after the missile’s cruise phase, might well pick out a different ship from the intended one in the congested waters of the strait — or even an island or other maritime feature.85 Scattering tanker traffic would also challenge an attacker’s ability to have a slow-moving, torpedo-launching asset in range of a tanker’s transit route and would expand the size of a minefield needed to threaten the strait to such a large area as to stretch mine-laying assets too thin. The net result would diminish war-related risks and would keep the cost of any political-military disruption manageable.

The functioning of Iran’s munitions, too, would add to the attackers’ challenge. For example, it is always the case that a significant fraction of missiles fail to launch and explode properly.86 Most of Iran’s missiles start their flights with a solid rocket booster, and temperatures higher than 100° F, common in the Persian Gulf, can lead to unsatisfactory performance.87 Even the United States has had significant reliability problems with some of its missiles. In the 1991 Gulf War, of the 307 Tomahawk cruise missiles fired, 19 experienced pre-launch problems and six failed to transition to the cruise phase.88 Iran’s missiles might be less reliable, whether sourced from old Chinese imports or more recent indigenous production.89 The Iranian military’s historical struggles with equipment maintenance (certainly by comparison to the U.S. military) might compound the reliability problem.90

Similar challenges apply to other types of munitions that Iran might use to threaten tankers in the strait. Sophisticated, modern mines are able to distinguish the type of ship above them using complex signal processing to combine inputs from acoustic, magnetic, pressure, and other kinds of sensors.91 Iran apparently has several thousand of these mines in its arsenal, but they are hard to maintain and deploy properly.92 For comparison, when Iraq deployed thousands of mines in 1990 before the Gulf War, 95 percent of its sophisticated mines did not function properly: some had dead batteries; others were deployed upside down or got stuck in the mud on the sea bottom.93 Iran’s IRGC might well do better, but the deployment would not be easy or certain.

Worse still for a potential attacker considering an effort to stop oil flows through Hormuz, each attack on a particular tanker would require a volley of multiple missiles to have a reasonable chance of stopping its transit. Tankers are very large ships, and unlike warships, they are not filled with sensitive electronics and magazines of dangerous munitions. Instead, tankers have multiple, independent cargo cells filled with a buoyant substance that is actually difficult to set ablaze, because the cells do not have a ready source of oxygen.94 Historically, tankers sink when their keel is broken, or they can be destroyed when they take so much damage scattered around the ship that they are not worth repairing. Localized damage from a single explosion is not enough, and cruise missiles tend to hit tankers in less vulnerable places. Many are designed to pop up and then dive into the deck of their targets, but most of the sensitive parts of a laden tanker such as the propeller and the engine room are below the water line. During the eight years of the Iran-Iraq War, anti-ship cruise missiles hit 150 large oil tankers, but only 36 of them were damaged beyond economic repair, and only one actually sank, having been struck repeatedly.95 Some damaged ships sailed to port for examination or repairs before they continued on their journeys, but in many other cases damage was so slight that transits were not even delayed. Because tankers continued to ply the Gulf for years despite the risk of attacks, a number of ships were hit on multiple occasions — as many as six in the cases of the Iranian tankers, Khark 4 and Taftan, showing just how resilient a “lucky” ship could be.96

The large volume of fire required to threaten the strait would pose substantial operational constraints.

The need to fire at least 50 missiles a day would pose a capacity constraint on a potential attacker like Iran. Various open-source estimates suggest that Iran’s total arsenal of relatively modern anti-ship missiles is small.97 In the late-1980s, it imported perhaps 100 C-201 Seersuckers,98 125 CS-801 Sardines,99 and 75 CS-802 Saccades from China.100 Since then, Iran has developed the capability to indigenously manufacture similar missiles, although there is no open-source information on their potential production rate or the size of the indigenously produced arsenal that Iran may have built up; we can only reliably say that Iran’s defense industry faces production constraints due to a combination of economic sanctions, corruption, and competing Iranian leadership priorities, and that it is prone to exaggerating its capabilities for propaganda purposes.101

Perhaps most importantly, the number of missiles that Iran has in its arsenal is not the only relevant constraint. Iran apparently imported only eight land-based launchers for the CS-801s and CS-802s and only has an additional twenty or so patrol boats modified to fire those missiles; it is not known whether Iran has produced any additional launchers itself.102 Even if Iran faced no attrition of its missile launchers, it would likely rapidly use up its entire arsenal of anti-ship missiles in a campaign against commercial shipping — and it seems quite plausible that Iranian leadership would be loath to use all of its missiles on commercial targets, because it might well want to save at least some to defend against potential threats from foreign warships.

The large volume of fire required to threaten the strait would also pose substantial operational constraints. Attackers would have to reload launchers over and over, either driving missiles from storage sites to meet the launchers or bringing the launchers back to the storage sites, perhaps multiple times a day. Coordinating those operations would be hard, especially if the drivers tried to vary their routes to hide them from enemy aircraft that would be eager to attack Iran’s limited arsenal of launchers. At a minimum, the need to evade oil exporters’ military efforts to destroy the launchers would make Iranian missile crews reluctant to leave hide sites and to turn on their targeting radars (which would reveal their locations); the threat would also make them eager to “scoot” back to those sites after firing and chary of the risk of reloading.103 Fear would likely degrade the effectiveness of the Iranian missile campaign and would surely increase Iranian command-and-control and resupply challenges, the normal fog of war, even for high-quality special forces. These operations are also exactly the type of complex operations that a politicized force like the IRGC, focused on irregular warfare, militia training, and public relations stunts, might especially struggle to perform.104

Meanwhile, the storage sites themselves would be vulnerable to air attack: Fixed locations such as warehouses are easy targets for modern strike weapons like those in the Saudi, Emirati, Kuwaiti, and other regional air forces.105 Even though Iran has proudly announced that it has built hidden, underground “missile cities” to hold stockpiles of weapons, traffic patterns and intelligence are likely to reveal the locations of their entrances, which could be bombed into rubble or could provide killing zones where soft-skinned trucks and launchers could easily be destroyed as they drove in and out.106 Of course, as previously discussed, the Gulf States’ militaries are not highly effective, and their air forces do not have a strong track record of hitting their bombing targets (e.g., in Libya and Yemen), and those facts would help the Iranians sustain their offensive. But attacks on fixed targets like warehouses, even if underground, and on vehicles driving on open roads maximize the utility of the Gulf States’ imported smart munitions and minimize the need for pilots’ individual initiative and complex tactics. Defending oil traffic in this scenario is relatively manageable for the oil exporters’ forces and is relatively difficult for the Iranian attackers’ forces. As a result, the promised long anti-shipping campaign might actually end up being rather short.

Iran could (and likely would) try to protect its mobile launchers and missile depots using its most sophisticated air defense systems. Creating an integrated air defense for a known, prepared area is easier than trying to provide air-defense cover for a moving line of attacking ground troops, so Iran might be relatively well positioned to threaten to impose some attrition on regional air forces trying to disrupt Iran’s anti-tanker effort.107 The air-defense threat would surely reduce the accuracy and effectiveness of the air strikes and complicate efforts to patrol and gather aerial intelligence on Iranian operations, but it would not stop local forces from engaging to protect their countries’ oil exports.

Any U.S. activities needed to defend the Strait of Hormuz would not require land-based U.S. deployments in advance of a crisis.

In the end, the challenge of Iranian air defense might motivate a U.S. military contribution to the military defense of the Strait of Hormuz. The United States could sell other regional powers weapons designed to target Iran’s air defenses (e.g., anti-radiation missiles). The United States could provide stand-off intelligence (e.g., from satellites) to help regional air forces with their target selection and mission planning. And the United States could continue its effort to develop mesh networks of inexpensive unmanned systems that could flood the airspace around the strait, acting as observers and potentially even kamikaze drones to attack Iran’s scarce assets like missile launchers.108 Even if cheap unmanned systems would be unlikely to have sensors sophisticated enough to track ground vehicles in complex terrain, they would be able to readily detect the plumes of Iranian missile launches, and once cued to a particular target, they could likely track that target, even with remote-operator assistance, if necessary. These U.S. activities would not require land-based U.S. deployments in advance of a crisis.

Similarly, some other capabilities that are not present among Persian Gulf militaries but that would be useful to clean up after an attempt to close the strait could also be provided by an over-the-horizon U.S. posture. For example, mine-hunting ships that would be needed to pick up even improperly deployed Iranian mines (because no one would know in advance which mines were functional) need not stay in the Gulf during peacetime. These ships would benefit from periodic exercises and continuing careful mapping of the region’s bathymetry, but if the United States wanted to provide that sort of mine-clearing service as a global public good, it could do it as an expeditionary mission rather than paying the political costs of peacetime local bases.109 Mine-hunting has not been an area of great success for recent U.S. military investment — in fact, the Littoral Combat Ships’ mine warfare mission module has been something of an acquisition disaster — so perhaps mine warfare should be an area of more focus for the United States military in the future.110

Overall, the goal for U.S. strategy in the Persian Gulf should be to provide a few particular military capabilities that might tip the balance against an aggressor.111 The United States should recognize that an effort to disrupt oil flows through the Strait of Hormuz faces enormous challenges even without any U.S. reaction. The United States can use that situation to its strategic advantage, minimizing the political and economic costs of achieving its key strategic objectives. Perhaps the greatest contribution that the United States could make to the continuing safe transit of oil through the Strait of Hormuz is to step back from the brink of conflict with Iran. After all, the key scenario that the Iranians identify as a reason to attack oil tanker traffic is to respond to an American strike against their homeland.

How to Pursue a Responsible Drawdown

Decades of U.S. military presence in the region have contributed to an artificial power imbalance. States that align with the United States feel they can rely on the guarantee of U.S. military might, while those deemed hostile must fear the possibility of invasion and regime change. The U.S. role influences the behavior of both: U.S. partners act with aggressive impunity, while U.S. adversaries seek avenues of resistance, including arming non-state militias and proxy forces. Rather than contributing to stability, the large presence of the U.S. military undermines U.S. interests by contributing to instability, which in turn can enmesh the United States in additional conflicts.

Given the absence of a realistic threat of regional hegemony from any country inside or outside the Middle East, the United States can safely reduce the unnecessary military burden of stationing tens of thousands of American troops in the region.

If the United States genuinely seeks a more stable Middle East, it must remove its weight from the scales and allow the region to recalibrate according to its actual multipolar balance of power. By allowing regional states to balance against each other, a more sustainable regional order can emerge, one not dependent on the eternal presence of thousands of U.S. troops. This approach would better serve U.S. interests, as a multipolar balance will both prevent hostile hegemony in the region and ensure that no party can close the Strait of Hormuz.

Consequently, to preserve Americans’ physical and economic well-being more effectively, the United States should significantly draw down its military presence in the region over a period of five to 10 years.

The United States should immediately begin discussions with regional powers currently hosting U.S. troops to allow them to prepare for the U.S. drawdown. If the drawdown is made contingent upon regional stability first being achieved, the United States will risk giving countries that enjoy U.S. protection an incentive to destabilize the Middle East to prevent American troops from ever going home.

The United States should instead encourage the development of a new regional security architecture for the Persian Gulf, while maintaining an offshore military presence that allows for intervention if necessary to protect U.S. interests. For such a security architecture to be successful and durable, it needs regional buy-in and ownership: Regional states should lead and drive this process themselves.

America’s continued military presence in the Middle East reflects outdated thinking. Given the absence of a realistic threat of regional hegemony from any country inside or outside the Middle East, the United States can safely reduce the unnecessary military burden of stationing tens of thousands of American troops in the region. Presence is not deterrence, nor is deterrence the only way to protect U.S. interests. With no realistic threat, there is nothing for active U.S. efforts to deter. Ultimately, the current distribution of power in the Middle East does not require much effort by the U.S. military, and it does not require any U.S. military presence.

Program

Countries/Territories

Citations

“Statement by Secretary of Defense Lloyd J. Austin III on the Initiation of a Global Force Posture Review.” U.S. Department of Defense, February 4, 2021. https://www.defense.gov/Newsroom/Releases/Release/Article/2494189/statement-by-secretary-of-defense-lloyd-j-austin-iii-on-the-initiation-of-a-glo/. ↩