Pathways to Pentagon Spending Reductions: Removing the Obstacles

Executive Summary

• Despite the changing security landscape, in which nonmilitary challenges ranging from pandemics to climate change are the gravest threats to the American people, United States security spending continues to focus on the Pentagon at the expense of other agencies and other policy tools.

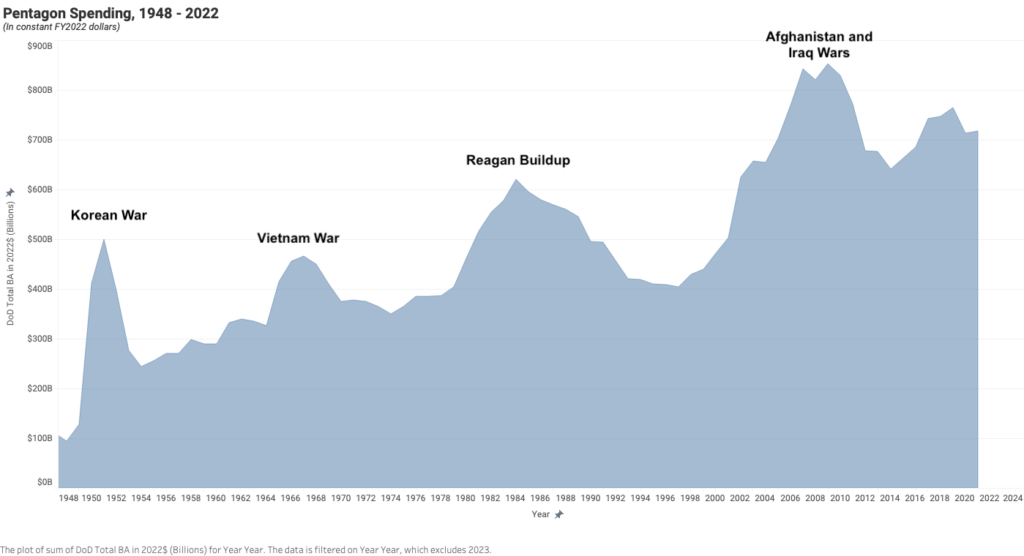

• In December 2021 Congress authorized $768 billion in spending on the Pentagon and related work on nuclear warheads at the Department of Energy — $25 billion more than the Pentagon asked for, and higher in real terms than peak budgets during the Korean and Vietnam wars and the Reagan buildup of the 1980s. An additional $10 billion in mandatory spending drove the final figure to $778 billion. There are press reports — yet to be officially confirmed by the administration — that the comparable proposal for spending on national defense in the fiscal year 2023 budget could exceed $800 billion.1

• The three main drivers of excessive spending on the Department of Defense are strategic overreach, pork-barrel politics, and corporate lobbying.

• An overly ambitious, “cover-the-globe” strategy that favors military primacy and endless war must be replaced with a strategy of restraint that would provide a more-than-sufficient defense while increasing investments in diplomacy, foreign economic development, and other nonmilitary tools of statecraft.

• Measures to weaken the influence of the military-industrial complex in the budget process should include prohibiting the armed services from submitting “wish lists” for items that are not in the Pentagon’s official budget request; slowing the “revolving door” between government departments and the weapons industry, and reducing the economic dependence of key communities on Pentagon spending, along with alternative government investments in areas such as infrastructure, green technology, and scientific and public health research.

Introduction: Where we stand

Any assessment of current Pentagon spending practices must begin by recognizing what enormous sums are already being provided to the Department of Defense. Current spending is at one of the highest levels since World War II. The $778 billion budget for national defense authorized by Congress in 2021 is substantially more in real terms than the U.S. spent annually at the peak of the Korean and Vietnam wars.2 The only time since World War II that the Pentagon budget was higher than its current level was around the height of the Iraq and Afghan conflicts, when the U.S. had roughly 200,000 troops in those two war zones, versus 2,500 now. (See Figure 1 on levels of Pentagon spending from 1948 to FY2020.)3

Any assessment of current Pentagon spending practices must begin by recognizing what enormous sums are already being provided to the Department of Defense.

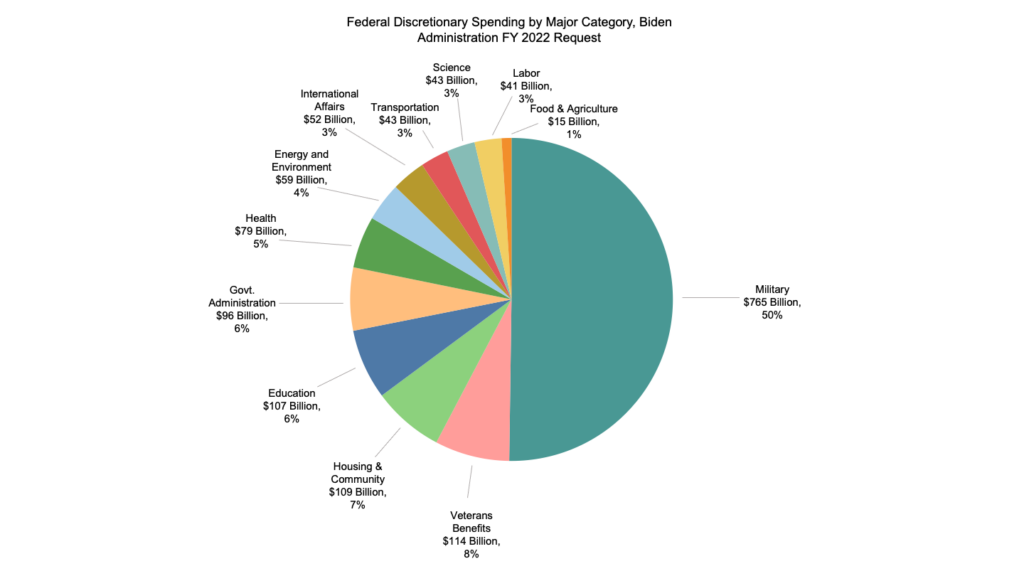

To put these numbers in perspective, the Pentagon budget is 13 times as large as the combined budgets of the State Department and the Agency for International Development. Further, Pentagon spending accounts for nearly half of all federal discretionary spending — the portion of the budget that Congress votes up or down every year, as opposed to entitlement programs such as Medicare and Social Security. (See Figure 2.)5

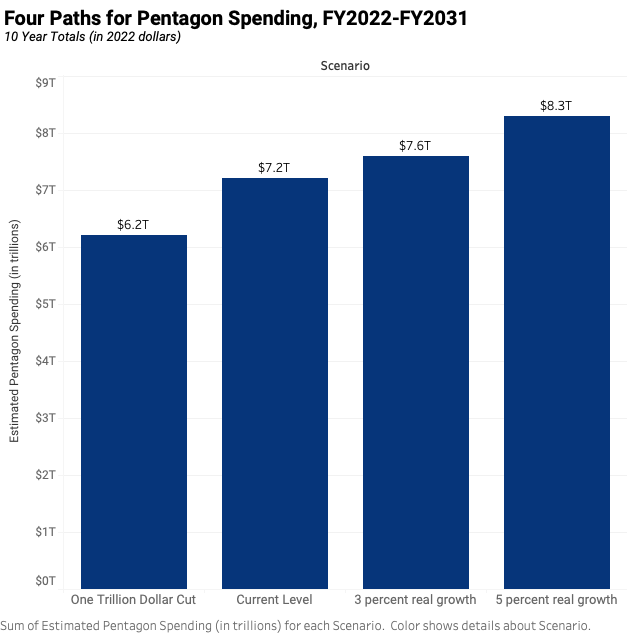

If the Pentagon budget remains at its current level, the Department of Defense will receive roughly $7.3 trillion over the next decade.7 This is more than four times the 10–year cost of the most recent iteration of President Biden’s Build Back Better plan, which would allocate $1.75 trillion over 10 years to address climate change, rebuild infrastructure, expand health care, and combat poverty — and which was rejected by key members of Congress as unaffordable.8

Congressional advocates of Pentagon spending propose increases of 3 percent to 5 percent per year, adjusted for inflation, for the foreseeable future.9 Doing so would push total military spending to more than $1 trillion per year by the end of this decade — an astonishing figure with no historical parallel other than U.S. spending during World War II.

Figure 3 charts four paths for Pentagon spending over the next decade: cutting $1 trillion dollars based on illustrative scenarios for reductions developed by the Congressional Budget Office; sustaining current levels; 3 percent real increases annually, and an annual increase of 5 percent in real terms.10 The approach outlined by the CBO is described in more detail below. As demonstrated, there are trillions of dollars at stake in the decision on what path to take on Pentagon spending — dollars that could be applied to fund other ways of addressing U.S. security priorities or to meet pressing domestic needs.

How did we get here? An outmoded strategy

Current U.S. defense strategy costs too much and achieves too little. In the drive to dominate the globe militarily, the United States has attempted to do almost everything, with the result that little is being done well.

On the counterterrorism side, the Costs of War Project at Brown University estimates that America’s post–September 11 wars have cost $8 trillion and counting, including the cost of caring for the hundreds of thousands of veterans of these conflicts.12 In the two largest wars, Iraq and Afghanistan, the United States has failed to meet its primary objectives of promoting stable, pro–U.S. governments and reducing the spread of global terrorism. The Taliban are now in power in Afghanistan. The U.S. intervention in Iraq helped bring a sectarian regime to power that created an environment in which the Islamic State, ISIS, could organize itself and seize large parts of northern Iraq — a development that took billions of dollars and thousands of troops to reverse.

While the Biden administration deserves credit for withdrawing American troops from Afghanistan, through 2020 the Pentagon carried out U.S. counterterror operations — air strikes, deploying special forces and other troops, training and equipping foreign militaries — in at least 85 countries, nearly half the world’s nation-states.13 How much DoD draws down these operations as the focus of U.S. strategy pivots to China and Russia remains to be seen. But the Pentagon’s global force posture report, released in November 2021, was a status quo document that did little to reduce the U.S. military footprint in the Middle East, even as it proposed increasing the U.S. troop presence in East Asia, suggesting that in the short term, at least, major changes in U.S. overseas deployments are not in the offing.14

At the regional level, the Iran nuclear accord — known formally as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, or JCPOA — is currently the subject of difficult negotiations, and there is no coherent strategy for limiting the growth of North Korea’s nuclear arsenal. These developments will make it more difficult for the United States to scale back its troop presence in the Middle East or reorient its force structure in Asia.

Perhaps the most significant development that will be used to argue for increasing Pentagon spending and sustaining or expanding the U.S. global military presence is the emergence of closer relations between Russia and China, the two main adversaries highlighted in current U.S. strategy documents and driving the national-security debate in Washington.

Current U.S. defense strategy costs too much and achieves too little. In the drive to dominate the globe militarily, the United States has attempted to do almost everything, with the result that little is being done well.

As noted, the United States is attempting to shift its policy, procurement, and force deployments toward great-power competition, as set out in the Pentagon’s 2018 National Defense Strategy and supplementary documents such as those released by the congressionally mandated National Defense Strategy Commission.15 Although the strategy gives lip service to “whole-of-government” approaches to the challenges Russia and China pose, it continues to view great-power relations through a military lens, as evidenced in recent moves such as the creation in September 2021 of the Australia–U.K.–U.S. alliance, AUKUS, and the Pentagon’s Pacific Deterrence Initiative, a multibillion-dollar program launched in spring 2021.16

Another major factor keeping Pentagon spending high is the department’s plan to spend up to $2 trillion developing and deploying a new generation of nuclear-armed bombers, submarines, and missiles over the next three decades. This is an exercise in nuclear overkill that is more likely to accelerate a dangerous and destabilizing arms race with Russia and China than bring greater security to the United States and its allies.17 Of particular concern is the plan to build a new intercontinental ballistic missile. Former Secretary of Defense William Perry has called ICBMs “some of the most dangerous weapons in the world” because a president would have only a matter of minutes to decide whether to launch them on warning of an attack, greatly increasing the risk of an accidental nuclear war based on a false alarm.18

All of the above factors help sustain high levels of Pentagon spending even as other challenges pose greater dangers to the lives and livelihoods of Americans and the populations of allied nations. A more restrained strategy that reduces the U.S. global military footprint must rely on allies to do more in their own defense while also reconsidering their roles for the long term. It must also take a more realistic view of the military challenges posed by Russia and China and put diplomacy first in addressing nuclear proliferation. Such a strategy would cost substantially less while doing a much better job of protecting the U.S. homeland and forgoing expensive and unnecessary foreign military entanglements. Adopting it will demand not only a thorough rethinking of current U.S. strategy; it will also require reforms in how Pentagon spending decisions are made.

How did we get here? Influence peddling and pork-barrel politics

As is well known, members of Congress across the political spectrum support high Pentagon budgets in part to sustain or expand military-related jobs in their states and districts. This leads to routine add-ons to the Pentagon’s budget, such as the authorization of $25 billion in additional spending to the FY2022 budget, as referenced above.19 Key to this effort was the decision by Pentagon budget boosters in Congress to embrace every item on the unfunded-priorities lists provided by the military services. These are essentially wish lists of items that didn’t make it into the Pentagon’s formal budget request.20 Another political and economic driver of high budgets is the fact that increasing Pentagon spending is a reliable and politically achievable way to pump money into the economy in general and the manufacturing sector in particular, as compared with more politically contested investments such as the president’s Build Back Better plan. This latter factor has created constituencies for continuing high defense spending among some American workers and communities.

A case in point is Lockheed Martin’s F–35 combat aircraft, a system of little relevance to the Pentagon’s new focus on China, which emphasizes the role of hypersonic weapons, cyber defense (and attack) capacities, unmanned vehicles, artificial intelligence, long-range strike systems, an expansion of the Navy, and the previously mentioned nuclear buildup. This militarized approach to the challenge from China is questionable in its own right, but there is no viable role in it for the F–35 even if it goes forward. The carriers that would deploy F–35s are vulnerable to Chinese missile attacks, and there is little likelihood of aerial dogfights between U.S. and Chinese combat aircraft. To add insult to injury, the F–35 is costly and dysfunctional, with 800 unresolved defects according to a 2021 Pentagon report.21 Not only is it the most expensive weapons program the Pentagon has ever undertaken; multiple assessments by the Project on Government Oversight and other independent analysts indicate that it may never be fully ready for combat.22

None of these problems has stopped Lockheed Martin and its allies in Congress from pushing the F–35 program toward the goal of 2,400 planes to be purchased by the mid–2030s.23 Lockheed even has a map on its website that shows the state-by-state impact of the 250,000 jobs it alleges to be tied to the program, information it regularly touts in lobbying Congress to add funding for the plane.24 The company claims to have subcontractors in 45 states and Puerto Rico.25 There is also an F–35 caucus in the House of Representatives. In May of 2021, the caucus organized a letter calling for more F–35s than the Pentagon had requested in its FY2022 budget proposal. The letter was signed by a bipartisan group of 132 members of the House — nearly one out of three members of that body.26

The F–35 caucus is composed primarily of members whose states or districts produce components of the plane. Lockheed Martin reinforces its job-based influence by spending roughly $7 million per year on campaign contributions and $13 million a year on lobbying, mostly focused on members of the House and Senate armed services and defense appropriations committees, where decisions on how much to spend on weapons are made.27

Lockheed Martin reinforces its job-based influence by spending roughly $7 million per year on campaign contributions and $13 million a year on lobbying, mostly focused on members of the House and Senate armed services and defense appropriations committees.

Another focus of lobbying by the military-industrial complex is the new ICBM, which will cost more than $264 billion over its lifetime.28 In September 2020, Northrop Grumman received a sole-source, $13.3 billion contract to kick off development of the missile.29 The company has 12 major partners in the development of the new system, including heavy hitters such as Lockheed Martin, Raytheon, and General Dynamics, which can add lobbying strength to efforts to keep funding for the program on track.30 An even bigger role is played by the Senate ICBM Coalition, made up of senators from Montana, North Dakota, Utah, and Wyoming — states that host ICBM bases or major ICBM development activities.31 One key member of the coalition is Sen. Jon Tester, the Montana Democrat who currently chairs the defense appropriations subcommittee of the Senate Appropriations Committee, and who therefore has considerable influence over how much is spent on weapons programs.

The ICBM Coalition has been extremely successful in thwarting any changes in ICBM policy or procurement, from limiting the reduction of the ICBM force under the New START treaty to blocking studies of alternatives to a new ICBM.32 Their dogged determination is fueled by the fact that ICBM bases and development support thousands of jobs in their states, comprising up to 10 percent of the workforce in some key localities.33

In addition to the jobs card, the weapons industry as a whole has numerous other tools of influence at its disposal, including campaign contributions, lobbyists with close connections to the Pentagon and key members of Congress, and think tank funding.34

For example, the 12 major companies involved in the development of the new ICBM employ a total of 380 lobbyists, an indicator of how much political power they have available in their efforts to influence Congress and the administration.35 Since the program’s launch in September 2020, Northrop Grumman and its subcontractors have contributed more than $1 million to the campaigns of members of the ICBM Coalition and more than $15 million to members of the armed services and defense appropriations committees in the House and Senate.36

According to statistics compiled by OpenSecrets, the nonprofit organization that collects data on campaign financing and lobbying, the weapons industry has spent $285 million on campaign contributions and $2.5 billion on lobbying during the Pentagon’s post–September 11 spending surge, while receiving $7 trillion in contracts in the same period.37 As a mathematical ratio, that is $28,000 in contracts for every dollar spent on lobbying. While some of these contracts would have proceeded with or without lobbying efforts, the ratio of lobbying dollars to contracts received helps explain why major contractors put so much money and effort into these activities. There is no question that lobbying pushes Pentagon spending levels higher than an objective assessment of U.S. security needs would require, but it is not possible to put a precise figure on these excess expenditures.

The numbers of lobbyists employed by the arms industry as a whole is similarly disturbing. In any given year, the industry employs an average of 700 lobbyists, well more than one for every member of Congress.38 By comparison, the auto and oil and gas industries had 656 and 746 lobbyists respectively in 2021.39 Most of them have passed through the revolving door from Congress or the Pentagon to corporations such as Lockheed Martin, Boeing, Raytheon Technologies, and General Dynamics.40 A recent Government Accountability Office report identified 1,700 generals, admirals, and Pentagon procurement officials who went to work in the arms industry after leaving government, including people such as Gen. Joseph Dunford, the former chair of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, who joined the board of Lockheed Martin a few months after leaving government service in September 2019.41 The GAO estimate is conservative, as it covers the revolving door hires of 14 contractors, not the defense sector as a whole.

The revolving door is pernicious in at least two respects. First, former military and Pentagon officials can use their contacts with former colleagues to seek favorable treatment for their corporate employers. Second and perhaps even more damaging, personnel still in the government may exercise lax oversight on the contractors because they want to get well-paying jobs with them when they leave the government.

A recent Government Accountability Office report identified 1,700 generals, admirals, and Pentagon procurement officials who went to work in the arms industry after leaving government.

As industry employees and officials join the government, the revolving door swings both ways. Four of the past five secretaries of defense have been board members, lobbyists, or top executives at major weapons contractors. These are James Mattis (General Dynamics), Patrick Shanahan (Boeing), Mark Esper (Raytheon), and Lloyd Austin (Raytheon).42 To his credit, Defense Secretary Austin has agreed to recuse himself from decisions involving Raytheon for four years. But given the company’s extensive business relations with the government — Raytheon builds missile defense systems, supplies nuclear weapons components, and provides bombs and missiles the U.S. sells to Saudi Arabia to conduct its brutal war in Yemen — deciding what decisions to step back from will be difficult indeed.43

The weapons industry is also a generous donor to think tanks that help shape public opinion and steer Congress on issues of foreign and military policy and weapons procurement. A 2020 study by the Center for International Policy found that contractors — and the Pentagon itself — had contributed roughly $1 billion to major think tanks over the six-year period to 2019. These include major organizations such as the Heritage Foundation, the Brookings Institution, the Center for Strategic and International Studies, and the Center for a New American Security.44 While these donations don’t always translate into research that supports the interests of specific manufacturers, companies make them with the clear intent of generating a general atmosphere favorable to robust military spending. In some cases, think tanks funded by the industry do advocate for the purchase of specific weapons systems, including nuclear weapons, armed drones, and the F–35. For example, the Center for a New American Security, which receives more than $500,000 a year from Northrop Grumman, has been a strong advocate for that company’s B–21 bomber program.45

Pentagon Contract Awards to the Top Five Contractors, FY2020

| Company | Pentagon Contracts | Revenue from Defense |

| Lockheed Martin | $75 billion | 95% |

| Raytheon Technologies | $27.8 billion | 94% |

| General Dynamics | $21.8 billion | 75% |

| Boeing | $21.7 billion | 45% |

| Northrop Grumman | $12.3 billion | 85% |

As noted, arms-company lobbying can yield impressive results. In 2020 a single corporation, Lockheed Martin, received an astounding $75 billion in Pentagon contracts, more than one and a half times the combined budgets of the State Department and the Agency for International Development for that year.47 The top five contractors — Lockheed Martin, Boeing, General Dynamics, Raytheon, and Northrop Grumman — received $166 billion in FY2020, more than one-third of the $420 billion in contracts the Pentagon handed out that year. (See table above.)48

What’s next? The new national defense strategy and the FY2023 budget

Despite its pledge to “put diplomacy first,” so far the Biden administration has doubled down on high levels of military spending. Its first Pentagon budget was comparable with the Trump administration’s in its final year, and the Biden team did not push back when Congress authorized $25 billion more than the Pentagon’s request. The Biden budget also embraced every element of the Pentagon’s three-decade plan to spend up to $2 trillion building a new generation of nuclear weapons, including two new nuclear weapons the Trump administration added.49 The Pentagon’s force posture review, released in September 2021, was a status quo document that suggested a slight reduction in the U.S. troop presence in the Middle East and a modest increase in U.S. force deployments in East Asia.50

Some analysts have suggested that the Biden administration’s business-as-usual approach to national-security spending reflects a new administration with multiple challenges finding its footing. Perhaps, some argue, the administration is focused more on questions such as the pandemic and investments in the domestic economy than on major changes in national-security budgets or strategy. The upcoming release of the FY2023 Pentagon budget and the administration’s National Defense Strategy will put this speculation to the test.

There are some glimmers of hope that a new approach could still be possible. The withdrawal of all U.S. forces from Afghanistan, significant proposed increases in the State Department budget, continued efforts to restore U.S. participation in the Iran nuclear deal, a commitment to investing in measures to curb the impacts of climate change, and climate discussions with China could all be elements of a new strategy, should the administration choose to change course from an overly militarized approach grounded in a futile quest for global primacy.

The top five contractors — Lockheed Martin, Boeing, General Dynamics, Raytheon, and Northrop Grumman — received $166 billion in FY2020, more than one-third of the $420 billion in contracts the Pentagon handed out that year.

In its first year in office, the Biden administration took a “both and” approach to strategy and budgeting rather than making tough choices — seeking both a military buildup in the Indo–Pacific and discussing climate issues with China; seeking both to increase the Pentagon budget while also spending more on diplomacy and on addressing the climate crisis. This approach fell afoul of the challenges posed by a divided Congress, however, so that Pentagon spending increases sailed through while climate investments stalled. Neither did the administration pursue climate discussions with China seriously enough, and little progress is evident so far on that front. Going forward, budgetary choices will have to be made if the United States is to generate the funds needed to address pandemics, climate change, and other nonmilitary challenges that more directly threaten human lives and livelihoods. The Pentagon can no longer be provided with a blank check.

Whether the need to make real choices will be reflected in the administration’s National Defense Strategy or its forthcoming FY2023 budget remains to be seen. As with its interim national-security strategy document, issued in March 2021, the National Defense Strategy is likely to make rhetorical references to the centrality of addressing climate change, public health, domestic economic strength, and the health of our democracy alongside traditional national-security concerns.51 However, the need to invest in reducing these nonmilitary risks may be overridden by a strong focus on the challenges posed by Russia and China, with major implications for military spending and deployments. And given its record so far, the Biden administration is unlikely significantly to reduce Pentagon spending in its FY2023 budget, especially given concerns generated by the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the possibility of an expansion of China’s nuclear arsenal.52

In its first year in office, the Biden administration took a “both and” approach to strategy and budgeting rather than making tough choices — seeking both to increase the Pentagon budget while also spending more on diplomacy and on addressing the climate crisis.

New approaches needed

Change on the scale needed to roll back the Pentagon and reduce the U.S global military footprint — and hence lessen the probability of U.S. involvement in costly and unnecessary wars — will require sustained effort and tough choices over years, not months. A concerted campaign of public education and policy advocacy will be needed to force U.S. strategy to catch up with current realities and fully acknowledge the limits — and the counterproductive consequences — of relying on the use of force and coercive economic sanctions as primary tools of foreign policy.

In recent years there have been a number of analyses of how a more realistic strategy could yield substantial savings in Pentagon spending, ranging from reports generated by the libertarian Cato Institute to the progressive Center for International Policy to the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office.53 Savings from a less ambitious military strategy are estimated to be on the order of $1 trillion or more over the next decade.54 One option explored by the CBO is an approach that “de-emphasizes use of U.S. military force in regional conflicts in favor of preserving U.S. control of the global commons (sea, air, space, and the Arctic), ensuring open access to the commons for allies and unimpeded global commerce.”55 A common feature of all of the analyses just noted is a significant reduction in the Pentagon’s global military footprint, including a 15 percent to 20 percent reduction in the size of the armed forces and a budget cut of 15 percent. While these studies raise important issues, a more detailed analysis that starts with a fresh definition of U.S. vital interests and prioritizes emerging and nontraditional security challenges is in order.

A concerted campaign of public education and policy advocacy will be needed to force U.S. strategy to catch up with current realities and fully acknowledge the limits — and the counterproductive consequences — of relying on the use of force and coercive economic sanctions as primary tools of foreign policy.

Even if a new strategy grounded in greater restraint and fewer costly global commitments can be developed, however, Pentagon spending is unlikely to go down without addressing the economics and politics of defense budget decision-making. On the one hand, nearly any alternative investment of public funds — from green energy to infrastructure to public health — will create from one and a half to two times as many jobs as spending on weapons and troops.56 On the other, the deployment of defense facilities in the states and districts of key defense decision-makers in Congress, and the political bias in favor of military spending over other priorities by members afraid of being seen as “soft on defense,” have so far blocked efforts to create alternatives for defense-dependent communities.

The security and economic benefits of transitioning away from economic dependency on high Pentagon spending would also be substantial. A 2017 study by Heidi Peltier for the Costs of War Project at Brown University found that a $125 billion annual cut in Pentagon spending that was instead invested in green manufacturing would create a net increase of 250,000 jobs.57 Reforming the budget process and crafting policies to provide alternative “pork” — jobs or other goods not tied to the weapons industry — is imperative if the Pentagon budget is to be rightsized in line with a more restrained and effective defense strategy.

Recommendations

Adopt a strategy of restraint. The Pentagon budget has been significantly reduced only at times of major historical shifts: the end of World War II and the Korean and Vietnam wars; the end of the Cold War, and (modestly) during the initial troop drawdowns from Iraq and Afghanistan, where troop strengths were reduced from more than 200,000 to a few thousand. Now should be such a time, given that the biggest challenges to the security of Americans are not grounded in great-power competition or regional military threats, but, rather, in nontraditional, transnational security threats such as climate change, pandemics, and a global surge in undemocratic policies and practices.58 Reducing Pentagon spending over the next few years will require a new defense strategy grounded in a more realistic assessment of the challenges posed by Russia and China, a diplomacy-first approach to regional threats, a less-militarized approach to dealing with global terrorism, and a sharp reduction in the U.S. global military footprint. One major area for reduction should involve the U.S. troop presence in the Middle East.59

Reduce the power of pork-barrel politics and corporate lobbying. The Pentagon budget authorized by Congress this year was, at $778 billion, one of the highest levels since World War II and, as noted, $25 billion higher than what the Pentagon asked for. In addition to being grounded in a misguided, military-first strategy, these immense sums reflect the power of influence-peddling and pork-barrel politics — notably contributing to elections campaigns, distributing weapons facilities and bases in the states and districts of key members of Congress, hiring former government officials to lobby for arms companies, funding think tanks, and tapping corporate officials for government panels that define “the threat.” Measures to weaken the grip of industry over the budget process should include prohibiting the armed services from submitting wish lists for items that are not in the Pentagon’s official budget requests; slowing the revolving door between government and the arms industry; prohibiting members of Congress from investing in defense industry stocks, and strengthening and expanding Congress’s truth-in-testimony rules to provide greater transparency regarding the role of experts from think tanks with ties to the arms industry in presentations to Congress. Measures should also be taken to reduce the economic dependency of key communities on Pentagon spending, including alternative government investments in sectors such as infrastructure, green technology, and scientific and public-health research. The major investments in green energy and alternative manufacturing technologies that are needed to address climate change will create millions of jobs that can absorb any workers displaced from reductions in Pentagon spending.60 Reducing economic dependency on Pentagon spending will be a long-term undertaking, but efforts to accomplish it must begin now.

William D. Hartung is a senior research fellow at the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft. His work focuses on the arms industry and the U.S. military budget. He was previously the director of the Arms and Security Program at the Center for International Policy and the codirector of the center’s Sustainable Defense Task Force. He is the author of Prophets of War: Lockheed Martin and the Making of the Military–Industrial Complex (Nation Books, 2011) and the coeditor, with Miriam Pemberton, of Lessons from Iraq: Avoiding the Next War (Paradigm Press, 2008).

From July 2007 through March 2011, Mr. Hartung was the director of the Arms and Security Initiative at the New America Foundation. Prior to that, he served as the director of the Arms Trade Resource Center at the World Policy Institute. He also worked as a speechwriter and policy analyst for New York State Attorney General Robert Abrams.

Hayden Schmidt produced graphics for this brief.

Program

Entities

Citations

Stone, Mike. “Exclusive – Biden to Seek More Than $770 Billion in 2023 Defense Budget, Sources Say.” Reuters, February 16, 2022. https://www.reuters.com/world/us/exclusive-biden-seek-more-than-770-billion-2023-defense-budget-sources-say-2022-02-16/; Mehta, Aaron. “$770 to $780 Billion Likely for Pentagon Budget Topline: Source.” Breaking Defense. February 17, 2022. https://breakingdefense.com/2022/02/770-780-billion-likely-for-pentagon-budget-topline-source/. ↩

Edmondson, Catie. “Senate Passes $768 Billion Defense Bill, Sends It to Biden.” The New York Times, December 15, 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/12/15/us/politics/defense-spending-bill.html. ↩

See Belasco, Amy. “The Costs of Iraq, Afghanistan, and Global War on Terror Operations Since 9/11.” Congressional Research Service, December 8, 2014. https://sgp.fas.org/crs/natsec/RL33110.pdf; DePetris, Daniel. “A Bad Start for U.S. Troops in Iraq.” Newsweek, January 5, 2022. https://www.newsweek.com/bad-start-new-year-us-troops-iraq-opinion-1665996. ↩

“DoD Budget Authority by Public Law Title (1948 to 2022),” Table 6–8. Department of Defense. National Defense Budget Estimates for FY2022, August 2021. https://comptroller.defense.gov/Portals/45/Documents/defbudget/FY2022/FY22_Green_Book.pdf.

The current dollars from this table were adjusted for inflation and presented in 2022 dollars using GDP (Chained) Price Index in the Office of Management and Budget’s Table 10.1, “Gross Domestic Product and Deflators Used in the Historical Table 1940–2026.” https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/hist10z1_fy22.xlsx.

At writing, the 2022 DoD budget has not been set. DoD’s budget authority in 2022 is assumed here to be $740.3 billion, in line with a $25 billion add-on to DoD’s original budget authorized by Congress. See also https://www.armed-services.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/FY22%20NDAA%20Agreement%20Summary.pdf. ↩“Congressional Budget Justification: Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs, Fiscal Year 2022.” U.S. Department of State. https://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/documents/FY_2022_State_USAID_Congressional_Budget_Justification.pdf. ↩

“President Biden’s FY 2022 Budget Request.” National Priorities Project, June 11, 2021. https://www.nationalpriorities.org/analysis/2021/president-bidens-fy-2022-budget-request/. ↩

“Illustrative Options for National Defense Under a Smaller Defense Budget.” Congressional Budget Office, October 2021. https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2021-10/57128-defense-cuts.pdf. ↩

Barber, William, Liz Theoharis, and Lindsay Koshgarian. “Congress Approved $778 Billion for the Pentagon. That Means We Can Afford Build Back Better.” Politico, December 16, 2021. https://www.politico.com/news/magazine/2021/12/16/congress-approval-778-billion-pentagon-afford-build-back-better-525130; Adamczyk, Alicia. “What’s In the Democrats’ $1.75 Trillion Build Back Better Plan.” CNBC.com, October 28, 2021. https://www.cnbc.com/2021/10/28/whats-in-the-democrats-1point85-trillion-dollar-build-back-better-plan.html. ↩

Kheel, Rebecca. “Battle Heats Up Over Pentagon Spending Plans.” The Hill, March 21, 2021. https://thehill.com/policy/defense/544126-battle-heats-up-over-pentagon-spending-plans. ↩

For a description and costing of the CBO’s restraint option, see “Illustrative Options.” Congressional Budget Office, Note 4. 25–27. ↩

See Note 3 for DoD and OMB sources used to calculate the 10–year spending figures. For the OMB’s inflation calculations, see https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/hist10z1_fy22.xlsx. The OMB does not provide estimates of inflation past 2026. We assume post–2026 inflation of 2 percent annually. ↩

Crawford, Neta C. “The U.S. Costs of the Post–9/11 Wars.” Costs of War Project. Watson Institute of International and Public Affairs. Brown University, September 1, 2021. https://watson.brown.edu/costsofwar/files/cow/imce/papers/2021/Costs%20of%20War_U.S.%20Budgetary%20Costs%20of%20Post-9%2011%20Wars_9.1.21.pdf. ↩

Savell, Stephanie. “United States Counterterror Operations 2018 to 2020.” Costs of War Project. https://watson.brown.edu/costsofwar/files/cow/imce/papers/2021/US%20Counterterrorism%20Operations%202018-2020%2C%20Costs%20of%20War.pdf. ↩

“DoD Completes 2021 Global Posture Review.” U.S. Department of Defense, November 29, 2021. https://www.defense.gov/News/Releases/Release/Article/2855801/dod-concludes-2021-global-posture-review/; Vlahos, Kelley. “Pentagon — U.S. Military Footprint Staying Right Where It Is.” Responsible Statecraft, November 30, 2021. https://responsiblestatecraft.org/2021/11/30/pentagon-u-s-military-footprint-staying-right-where-it-is/. ↩

“Summary of the 2018 National Defense Strategy of the United States of America: Sharpening the American Military’s Competitive Edge.” U.S. Department of Defense, January 19, 2018. https://dod.defense.gov/Portals/1/Documents/pubs/2018-National-Defense-Strategy-Summary.pdf; “Providing for the Common Defense: The Assessment and Recommendations of the National Defense Strategy Commission.” United States Institute of Peace, November 13, 2018. https://www.usip.org/sites/default/files/2018-11/providing-for-the-common-defense.pdf. ↩

Wintour, Patrick. “What Is the AUKUS Alliance and What Are Its Implications?” The Guardian, September 16, 2021. https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2021/sep/16/what-is-the-aukus-alliance-and-what-are-its-implications; Shidore, Sarang. “AUKUS military alliance is another Western attempt to isolate China.” Responsible Statecraft, September 16, 2021, https://responsiblestatecraft.org/2021/09/17/uk-us-australian-nuclear-sub-deal-is-another-western-attempt-to-isolate-china/; Eversden, Andrew. “Pacific Deterrence Initiative Gets $2.1 Billion Boost in Final NDAA.” Breaking Defense, December 7, 2021. https://breakingdefense.com/2021/12/pacific-deterrence-initiative-gets-2-1-billion-boost-in-final-ndaa/. ↩

Reif, Kingston, and Alicia Sanders–Zakre. “U.S. Nuclear Excess: Understanding the Costs, Risks, and Alternatives.” Arms Control Association, April 2019. https://www.usnuclearexcess.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Report_NuclearExcess2019_update0410.pdf; Cirincione, Joseph. “Achieving a Safer U.S. Nuclear Posture.” Quincy Brief No. 19. Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft, February 7, 2022. https://quincyinst.org/report/achieving-a-safer-u-s-nuclear-posture/. ↩

Perry, William J. “Why It’s Safe to Scrap America’s ICBMs.” The New York Times, September 30, 2016. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/09/30/opinion/why-its-safe-to-scrap-americas-icbms.html. ↩

Shane III, Leo, and Joe Gould. “Congress Passes Defense Policy Bill With Budget Boost, Military Justice Reforms.” Military Times, December 15, 2021. https://www.militarytimes.com/news/pentagon-congress/2021/12/15/congress-passes-defense-policy-bill-with-budget-boost-military-justice-reforms/. ↩

Lautz, Andrew. “Lawmakers Cave to ‘Wish Lists’ and Give Pentagon Money It Doesn’t Need.” Responsible Statecraft, July 29, 2021. https://responsiblestatecraft.org/2021/07/29/lawmakers-cave-to-wish-lists-and-give-the-pentagon-money-it-doesnt-need/. ↩

Capaccio, Anthony. “Lockheed F–35s Tally of Flaws Tops 800 As ‘New Issues’ Surface.” Bloomberg News,July 13, 2021. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-07-13/lockheed-f-35-s-tally-of-flaws-tops-800-as-new-issues-surface#:~:text=Lockheed%20Martin%20Corp.’s%20F,office%20and%20Congress’s%20watchdog%20agency. ↩

Insinna, Valerie. “Watchdog Group Finds F–35 Sustainment Costs Could Be Headed Off Affordability Cliff.” Defense News, July 7, 2021. https://www.defensenews.com/air/2021/07/07/watchdog-group-finds-f-35-sustainment-costs-could-be-headed-off-affordability-cliff/; Grazier, Dan. “The F–35 and Other Legacies of Failure.” Project on Government Oversight, March 19, 2021. https://www.pogo.org/analysis/2021/03/the-f-35-and-other-legacies-of-failure/. ↩

Robin, Sebastian. “The Crazy Story of How the Stealth F–35 Fighter Was Born.” The National Interest, February 24, 2019. https://nationalinterest.org/blog/buzz/crazy-story-how-stealth-f-35-fighter-was-born-45387. ↩

“F–35 Economic Impact.” Lockheedmartin.com. Lockheed Martin Corporation, February 1, 2022. https://www.f35.com/f35/about/economic-impact.html. ↩

“F–35 Global Partnership.” Lockheedmartin.com, February 1, 2022. https://www.lockheedmartin.com/en-us/products/f-35/f-35-global-partnership.html. ↩

“Joint Strike Fighter Caucus Announces Strong Support of the F–35 Joint Strike Fighter.” United States Representative John Larson, May 21, 2021. https://larson.house.gov/media-center/press-releases/joint-strike-fighter-caucus-announces-strong-bipartisan-support-f-35. ↩

See OpenSecrets. https://www.opensecrets.org/orgs/lockheed-martin/summary?id=D000000104. ↩

Capaccio, Anthony. “New ICBM Could Cost Up to $264 Billion Over Decades.” Bloomberg News, October 3, 2020. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-10-03/new-u-s-icbms-could-cost-up-to-264-billion-over-decades. ↩

Harper, Jon. “Northrop Grumman Lands $13 Billion Deal for New Nuclear Missiles.” National Defense, September 8, 2020. https://www.nationaldefensemagazine.org/articles/2020/9/8/northrop-grumman-lands-13-billion-deal-for-new-nuclear-missile-system. ↩

Weisgerber, Marcus. “Northrop Announces Suppliers for New ICBM. Boeing Is Not on the List.” Defense One, September 16, 2019. https://www.defenseone.com/business/2019/09/northrop-icbm/159886/. ↩

Hartung, Willam D. “Inside the ICBM Lobby: Special Interests or the National Interest?” Center for International Policy, March 2021. https://3ba8a190-62da-4c98-86d2-893079d87083.usrfiles.com/ugd/3ba8a1_89fe183f8a164e22a2fa29d4d6381d7b.pdf. See also Hartung. “Inside the ICBM Lobby: Special Interests or the National Interest?” Arms Control Today, May 2021. https://www.armscontrol.org/act/2021-05/features/inside-icbm-lobby-special-interests-national-interest. ↩

Hartung. “Inside the ICBM Lobby.” The Senate ICBM Coalition organized dozens of letters and visits to Pentagon and White House officials and Congressional colleagues, advocating for a new ICBM; successfully lobbied against amendments that called for studies of alternatives to a new ICBM or reductions in ICBM funding, and persuaded the Obama administration to limit reductions of ICBMs under the New START Treaty, among other actions. ↩

Hartung. “Inside the ICBM Lobby.” March 2021. ↩

Freeman, Ben. “U.S. Government and Defense Contractor Funding of America’s Top 50 Think Tanks.” Center for International Policy, October 2020. https://3ba8a190-62da-4c98-86d2-893079d87083.usrfiles.com/ugd/3ba8a1_c7e3bfc7723d4021b54cbc145ae3f5eb.pdf. ↩

Freeman. “U.S. Government and Defense Contractor Funding.” ↩

Freeman. “U.S. Government and Defense Contractor Funding.” ↩

Auble, Dan. “Capitalizing on Conflict: How Defense Contractors and Foreign Nations Lobby for Arms Sales.” Center for Responsive Politics, February 25, 2021. https://www.opensecrets.org/news/reports/capitalizing-on-conflict; Hartung, William D. “Profits of War: Corporate Beneficiaries of the Post–9/11 Pentagon Spending Surge.” Center for International Policy and Costs of War Project, September 13, 2021. https://watson.brown.edu/costsofwar/files/cow/imce/papers/2021/Profits%20of%20War_Hartung_Costs%20of%20War_Sept%2013%2C%202021.pdf. ↩

Author’s calculation based on the OpenSecrets database, https://www.opensecrets.org/federal-lobbying. ↩

Open Secrets database. ↩

Smithberger, Mandy. “Brass Parachutes: The Problem of the Pentagon Revolving Door.” Project on Government Oversight, November 5, 2018. https://www.pogo.org/report/2018/11/brass-parachutes/. POGO maintains a “revolving door” database. ↩

“Post–Government Employment Restrictions: DOD Could Further Enhance Its Compliance Efforts Related to Former Employees Working for Defense Contractors.” Government Accountability Office, September 9, 2021. https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-21-104311; Mehta, Aaron. “Lockheed Adds Dunford, Former Top Military Officer, to Board.” Defense News, January 25, 2020. https://www.defensenews.com/industry/2020/01/25/lockheed-adds-dunford-former-top-us-military-officer-to-board/#:~:text=WASHINGTON%20%E2%80%94%20Lockheed%20Martin%20has%20added,1; see also Smithberger. “Brass Parachutes.” ↩

Lipton, Eric, Kenneth P. Vogel, and Michael LaForgia. “Biden’s Choice for Pentagon Faces Questions on Ties to Contractors.” The New York Times. December 8, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/12/08/us/politics/lloyd-austin-pentagon-military-contractors.html. ↩

Weisgerber, Marcus. “Austin Pledges to Recuse Himself From Military Decisions Involving Raytheon.” Defense One, January 20, 2021. https://www.defenseone.com/business/2021/01/austin-pledges-recuse-himself-military-decisions-involving-raytheon/171496/; see also “Smarter Defense Systems.” Raytheon Technologies. https://www.rtx.com/our-company/what-we-do/defense; Hartung, William D., and Cassandra Stimpson, “U.S. Arms Sales to Saudi Arabia — The Corporate Connection.” Center for International Policy, July 2019. https://static.wixstatic.com/ugd/fb6c59_bd62e10ae7b745069e9a6fa897de6a39.pdf. ↩

Freeman. “U.S. Government and Defense Contractor Funding.” ↩

Freeman. “U.S. Government and Defense Contractor Funding.” ↩

“Top 100 for 2021.” Defense News, July 12, 2021. https://people.defensenews.com/top-100/. ↩

“Congressional Budget Justification: Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs, Fiscal Year 2021.” U.S. Department of State, February 2020. https://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/documents/9276/FY-2021-CBJ-Final.pdf. ↩

“Top 100 Contractors Reports.” Federal Procurement Data System. https://sam.gov/reports/awards/static; “Defense Primer: Department of Defense Contractors.” Congressional Research Service, December 17, 2021. https://sgp.fas.org/crs/natsec/IF10600.pdf. ↩

Reif and Sanders–Akre. “U.S. Nuclear Excess.” Note 10. ↩

Vlahos. “Pentagon: U.S. Military Footprint.” ↩

“Interim National Security Strategic Guidance.” The White House, March 3, 2021. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/03/03/interim-national-security-strategic-guidance/. ↩

Korda, Matt, and Hans Kristensen. “A Closer Look at China’s Missile Silo Construction.” Federation of American Scientists, November 21, 2021. https://fas.org/blogs/security/2021/11/a-closer-look-at-chinas-missile-silo-construction/. ↩

“Building a Modern Military: The Force Meets Geopolitical Realities.” Cato Institute, 2020. https://www.cato.org/sites/cato.org/files/2020-05/white-paper-building-a-modern-military.pdf; “Sustainable Defense: More Security, Less Spending.” Sustainable Defense Task Force. Center for International Policy, June 2019. https://static.wixstatic.com/ugd/fb6c59_59a295c780634ce88d077c391066db9a.pdf; Congressional Budget Office. “Illustrative Options.” https://www.cbo.gov/publication/57128. ↩

Congressional Budget Office. “Illustrative Options.” 1. ↩

Congressional Budget Office. “Illustrative Options.” ↩

Garrett–Peltier, Heidi. “War Spending and Lost Opportunities.” Costs of War Project. Watson Institute of International and Public Affairs. Brown University, 2019. https://watson.brown.edu/costsofwar/files/cow/imce/papers/2019/March%202019%20Job%20Opportunity%20Cost%20of%20War.pdf. ↩

Garrett–Peltier, Heidi. “Cut Military Spending, Fund Green Manufacturing.” Costs of War Project. Watson Institute of International and Public Affairs. Brown University, November 13, 2019. https://watson.brown.edu/costsofwar/files/cow/imce/papers/2019/Peltier%20Nov2019%20Short%20GND%20CoW.pdf. ↩

See Jentlesen, Bruce W. “Be Wary of China Threat Inflation.” Foreign Policy, July 30, 2021. https://foreignpolicy.com/2021/07/30/china-threat-inflation-united-states-soviet-union-cold-war/; Bacevich, Andrew. After the Apocalypse: America’s Role in a World Transformed. New York. Metropolitan Books, 2021. 166–172. ↩

Gholz, Eugene. “Nothing Much to Do: Why America Can Bring All Troops Home From the Middle East.” Quincy Paper No. 7. Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft, June 24, 2021. https://quincyinst.org/report/nothing-much-to-do-why-america-can-bring-all-troops-home-from-the-middle-east/. ↩

Nilsen, Ella. “Democrats’ Clean Energy Program Would Create 8 Million Jobs by 2031, Analysis Shows.” CNN.com, September 9, 2021. https://www.cnn.com/2021/09/09/politics/clean-electricity-program-jobs-reconciliation-climate/index.html. ↩