Costly Adaptation, Not Capitulation: Iran’s Likely Trajectory Under the Post—JCPOA Pressure Campaign

Executive Summary

Following the 12-day war with Israel, the reinstatement of U.N. Security Council snapback sanctions, and Washington’s renewed maximum pressure campaign, the Islamic Republic is now experiencing the most intense external political and economic coercion in its history.

Yet this strategy is unlikely to deliver on the United States’ intended goals of regime change or nuclear restraint. Instead, it is pushing Iran toward deeper poverty, more complex security postures, and a trajectory that increases, not reduces, the likelihood of a costly military confrontation.

From Tehran’s standpoint, Washington’s objectives extend beyond nuclear limits toward regime change. Negotiations are viewed as potential ambushes for another round of conflict, and accepting U.S. demands would be politically humiliating. In this deadlock, Tehran opts for resistance as the only survivable path.

Iran has adapted its economy to withstand the strains caused by far-reaching Western sanctions through a wide range of measures. These include diversification, trade restructuring, de-dollarization, alternative banking pathways including offshore banking to circumvent U.S. control, shifting trade eastward to China (now Iran’s top trading partner), and import substitution in manufacturing and agriculture.

When intense external political and economic pressures fail to produce the expected capitulation, a misinterpretation of Iran’s vulnerability could invite further pressure. Without a credible diplomatic path, this dynamic creates the possibility for a dangerous escalation cycle. While U.S. strikes on Iran this past June did considerable damage to nuclear facilities, Iran retains enough nuclear fissile material and technical expertise to preserve a position of strategic ambiguity.

Iran’s adaptation strategy has preserved core state function and regime cohesion, even as the general public has suffered. Increasingly, Iran has become a patron welfare state, rewarding regime loyalty and shielding public employees and politically connected groups from the effects of sanctions, shifting economic burden onto the broader, politically disconnected public. By 2027, Iran will have approximately 10 million more people in poverty, a figure that could bring Iran’s overall poverty rate to 70 percent.

Prolonging hardship for the Iranian public will not succeed in toppling Iran’s leaders or advancing U.S. objectives; the Iranian regime itself has proven adept at absorbing the costs of Western pressure, adapting its economy, and retaining nuclear leverage.

America’s pressure-only policy only heightens the risk of a major Middle East war and thus should be discarded. The U.S. should instead reengage diplomatically with the Iranian regime toward the goal of stringent limits on Iranian nuclear capabilities in return for economic relief.

Introduction

In the first days of President Trump’s second term, Washington doubled down on a maximum-pressure strategy against Iran, elevating coercion to a scale unprecedented in the history of the Islamic Republic since 1979. The wager in Washington is clear: that escalation can deliver surrender or collapse. Will this new combination of economic, political, and military pressure force Iran’s capitulation? Will this renewed maximum-pressure campaign compel Iran to “surrender,” as President Trump has envisioned? These questions now sit at the center of Washington’s strategy.

In late September 2025, Britain, France, and Germany activated the U.N.’s sanctions snapback mechanism, reinstating all relevant U.N. Security Council resolutions on Iran’s nuclear activities that were lifted under the 2015 nuclear deal. Russia and China dismissed this move, urging the international community not to recognize the renewed sanctions, which were imposed from 2006 to 2010 but lifted under the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, or JCPOA, in 2015. Despite this procedural dispute within the U.N. Security Council, the Iran deal, which was mainly splintered by the 2018 U.S. withdrawal, has now run its course. Both sides implicitly acknowledge the same reality: The JCPOA has effectively come to an end.

With the 12-day war, the reimposition of U.N. sanctions, and the lack of a credible diplomatic path to resolve Iran’s nuclear program, a new phase of intensified economic and political pressure has opened, unprecedented in the history of the Islamic Republic since 1979. Speculation about a second Israeli strike or military confrontation with the U.S. has deepened uncertainty and strained the economy. While Washington tightens the screws on Tehran, the strikes on nuclear facilities have constrained enrichment capacity, and more than 2,800 U.S. sanctions have deepened chronic stagflation and fiscal deficits in Iran. With the fall of Assad in Syria in late 2024 and other regional shifts weakening the Axis of Resistance and undermining Iran’s regional deterrence, many in Washington see a rare opportunity to force concessions or even cause regime collapse.

Facing what it perceives as an existential threat, Tehran has adopted a cautious posture and ambiguity, owing to either indecision or deliberate restraint. With broad internal consensus that U.S. policy has shifted back toward regime change, the key question is which survival strategy will be most effective for the next three years: an inclusive resistance strategy that maintains deterrence while pursuing selective deescalation and targeted economic openings, or an exclusive strategy that prioritizes security, centralizes control, and limits engagement, even at higher social costs.

This policy brief examines the economic and social impacts of the Washington pressure campaign on Iran, and Tehran’s coping strategies and adoption tools. It finds that escalation is unlikely to succeed; as in 2018–2020, measures have fallen most heavily on ordinary citizens with limited political influence, while state institutions retain sufficient resources to sustain core functions and security priorities. The result is greater economic decline and social hardship at home, further consolidation of a security-centric state, and continued nuclear advancement outside a negotiated framework. In short, the campaign is unlikely to achieve its stated nonproliferation aims or deliver regime change or unconditional surrender, leaving core Western objectives unmet.

Why Iran’s strategic calculus remains the same

Tehran sees itself in a deadlock: There is no credible path to negotiations with the United States, yet further escalation risks a costly war that could end the regime, albeit at significant cost to the U.S. and its regional allies. Despite the deadlock, Iran’s strategic focus remains the same, emphasizing deterrence and regime survival.

Iran reads U.S. pressure as directed at regime change rather than at policy or behavioral change. Washington’s humiliating rhetoric of unconditional surrender collides with a proud national identity in Iran, raising the domestic political cost of compromise. Many in Tehran also believe that Israel strongly shapes U.S. policy toward Iran and seeks to incapacitate Iran as a regional rival, regardless of Iran’s political makeup. More broadly, Tehran frames the confrontation with Washington as a zero-sum, identity-laden issue, rather than a bounded technical dispute. Conceding under coercion would, in its view, validate a regime-change strategy, erode domestic legitimacy, and invite additional pressure. By contrast, absorbing costs while maintaining deterrence preserves bargaining leverage, signals resolve to domestic and regional audiences, and protects regime dignity.

In this setting, resistance is not a preferred option — it is the only viable choice. Between war and capitulation, Iran is pursuing a third path: strategic patience with ambiguity to restore deterrence and resilience over time, demonstrating the failure of a pressure-first approach.

The failure of nearly three decades of engagement experience with the U.S. has had a significant impact on Iran’s strategic calculations. In 2003, following the U.S. invasion of Iraq and amid fears of military confrontation, Iran quietly offered to resolve all outstanding disputes with Washington comprehensively. Tehran proposed accepting the Arab League’s 2002 two-state initiative, ceasing support for anti–Israeli militant organizations, transforming Hezbollah into an exclusively political entity, and ensuring complete collaboration with the International Atomic Energy Agency, or IAEA.1In exchange, Iran sought sanctions relief and formal recognition of its legitimate security interests. The Bush administration rejected the offer, judging Iran too vulnerable to merit serious negotiation. After 12 years of negotiations and sanctions, and a change of U.S. administrations from Bush to Obama, Iran and the U.S. reached an agreement to resolve its nuclear issue. Iranian moderates promoted the 2015 deal to the public by arguing that resolving the nuclear issue would end Iran’s isolation and lead to normalized economic relations with the West. That promise collapsed in 2018 when the U.S. unilaterally quit the deal, under the Trump administration, and the E.U. failed to uphold its commitments to maintain the JCPOA after the U.S. withdrawal.

Trump’s rhetoric in his second presidential campaign about ending regional conflicts and prioritizing “America First” initially generated cautious optimism in Tehran, which grew in early 2025 after Trump sent a direct letter to Iran’s supreme leader.2Foreign Minister Abbas Araqchi publicly welcomed the invitation to talks and floated potential U.S. investment opportunities of up to $1 trillion in Iran.3The opening, however, closed quickly. Within two months of initial talks, U.S. demands swung from signaling acceptance of Iran’s right to low-level enrichment to insisting on zero enrichment, and ultimately to calling for “unconditional surrender.”4A joint U.S.–Israeli strike on IAEA–monitored nuclear facilities in June 2025 functioned, in Iran’s president’s words, as “a bomb on the negotiating table,” extinguishing residual trust in diplomacy.5Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu of Israel later touted this “unmatched coordination” with Washington as unprecedented in Israel’s 77-year history.6In a similar situation in 2018, Netanyahu had boasted about his role in leading the U.S. withdrawal from the JCPOA, saying, “We convinced the U.S. president [to exit the JCPOA], and I had to stand up against the whole world and come out against this agreement.”7To Iranian eyes, Israel wields outsized influence in driving U.S. policy toward a confrontational stance and pulls Washington toward direct conflict regardless of negotiations. From Tehran’s perspective, these episodes confirm that the ultimate U.S.–Israeli objective is a weakened or compliant Iran, and that nuclear concessions alone cannot satisfy that aim. As long as this assessment holds, Iran’s strategy will prioritize deterrence and regime survival over economic relief.

Iran’s tools of resistance and adaptation

Over the past two decades, the Islamic Republic has used a combination of strategies to withstand external pressure while maintaining regime stability. This approach contains economic diversification, trade restructuring, eastward economic integration, selective import substitution, and sanctions evasion, all supported by stringent internal security measures to withstand sanctions and await a more favorable policy environment in Washington.

Over the past decade, Iran’s economy has adapted to sanctions through diversification and evasion, in particular, albeit at a high cost.8Under sanctions, Iran has reorganized its trade practices and shifted eastward by using intermediaries, reflagging tankers, and bartering or settling transactions in local currency to maintain the flow of exports and essential imports. China has surpassed the European Union to become Iran’s biggest trading partner, while Iran has increased business with Russia and neighboring countries like Iraq, Turkey, Afghanistan, and the UAE. This eastward shift has partially reshaped Iran’s trade composition. For example, non-oil exports to nearby countries have grown.9Oil exports continue to reach China through opaque arrangements and a “shadow fleet” of illegal tankers, with independent Chinese refiners (referred to as teapots) still processing Iranian crude despite U.S. efforts to block these routes.10Iran has also started a new “barter-like” or “oil-for-infrastructure” arrangement with Chinese state-owned enterprises, including the insurer Sinosure and the financial firm Chuxin. It is estimated that approximately $8.4 billion of Iran’s oil revenue was allocated to fund these projects in 2024.11

As part of Tehran’s broader de-dollarization strategy to reduce dependence on Western banking systems, Iran has created several alternative banking pathways to maintain revenue outside U.S. control. Tehran started using “offshore” banking, officially licensing Cyrus Offshore Bank on Kish Island as a cover for the central bank to manage trade payments.12In late 2023, the central bank authorized the use of a domestically developed the Cross-Border Interbank Messaging System for international transactions, linking Iranian banks with international partners, such as China’s Bank of Kunlun, a key channel for oil payments. Iran also plans to shift much of its trade with China to the renminbi as an international payment currency and use China’s cross-border international payment system for clearing and payments.13Tehran has also accelerated plans for a central bank digital currency, known as the digital rial.14Pilot programs were underway on Kish Island and with major banks like Bank Melli and Bank Tejarat.15In late 2024, Iran’s central bank unveiled ACUMER, a new bank messaging platform for Asian Clearing Union members designed to bypass SWIFT and facilitate sanctioned trade.16Tehran is also exploring the use of digital currencies to mitigate sanctions. In August 2022, Iran authorized its first official import transaction paid in cryptocurrency, amounting to $10 million, as a pilot initiative to circumvent the dollar-based financial system.17In January 2023, Tehran and Moscow linked their interbank communication networks, enabling Iranian banks to conduct transactions with Russian banks without using SWIFT.18The two countries have also connected their payment card networks, Iran’s Shetab and Russia’s Mir, allowing Iranian and Russian consumers to use each other’s bank cards.

As part of Iran’s plan to connect with Eurasian transportation routes, the country built new logistics infrastructure. In May 2025, the first direct freight train from Xi’an, China, arrived in Tehran after traveling approximately 10,400 kilometers, cutting transit time from 40 to 15 days.19In March 2025, Iran and Russia agreed to finalize the missing link (162 kilometers) in the western branch of the International North–South Transport Corridor, connecting Russian ports to Iran, the Persian Gulf, and India.20Of course, the scale of overland trade remains small compared to seaborne commerce, so these new corridors complement rather than replace Iran’s tanker traffic. They provide a safe and dependable overland path for Iranian exports, particularly oil, by reducing reliance on maritime routes that are vulnerable to disruptions.

Prolonged sanctions have also encouraged selective self-reliance within the country. Tehran has sought to increase domestic production across sectors such as food and pharmaceuticals to mitigate the impact of import restrictions. This import-substitution effort has led Iran to produce more of its essential consumer goods locally. For instance, Iranian pharmaceutical companies imported 80 percent of their required pharmaceutical raw materials in 2010; this proportion declined to 30 percent in 2024.21Sanctions-triggered currency devaluation made Iranian goods cheaper abroad, boosting the profitability of non-oil manufacturing and encouraging local production in place of imports.22Although Iran has diversified trade links and strengthened non-oil industries, which have helped ease some sanctions pressure and boost its economic resilience, these adaptive measures have not eliminated the sanctions’ negative impact on growth and development.

Alongside economic adaptation, Tehran has relied on nuclear escalation as a resistance tactic to deter further coercion and to leverage bargaining power, as Iran’s nuclear timeline illustrates. In November 2004, Iran, along with France, Germany, and the U.K., reached what is known as the Paris Agreement.23Iran agreed to voluntarily suspend its nuclear program until a final “grand bargain” was reached.24The agreement soon failed, and Iran restarted uranium enrichment in April 2006.25After the failure of the Geneva talks in 2009, Iran increased enrichment to 20 percent and expanded the number of operating centrifuges.26When the U.S. withdrew from the JCPOA in 2018, Iran maintained compliance with the deal, stating that it would remain committed if the E.U. could guarantee the deal’s economic benefits. However, after about a year and a half, Iran started gradually exceeding its limits while advancing research on more powerful centrifuges. By December 2024, enrichment had increased from 3.5 percent to over 60 percent; the stockpile of enriched uranium had grown from just over 300 kilograms to nearly 9,800 kilograms; and the number of installed centrifuges had increased from around 6,000 to roughly 17,000, including advanced IR–6 models. In Tehran’s view, these measures were not an end but a means to deter coercion and gain leverage, and to signal that coercive policies elicit more provocative behavior, as the 2018–2020 attacks on Aramco, the downing of U.S. drones, and strikes on bases such as Ain al-Assad underscored.27However, this approach carried clear risks of blowback, as the recent U.S. attacks on nuclear sites indicate. While the June strikes on Iran’s nuclear sites limited Tehran’s nuclear leverage, they did not entirely eliminate it. The Islamic Republic retains both the technical expertise and enriched material, especially its stockpile. Adopting a strategy of strategic ambiguity, Tehran intentionally obscures the scope of its current capabilities to maintain its leverage in negotiations. In Tehran’s view, its nuclear card may be less visible, but it remains intact — diminished but not dismantled.

Sanctions have undoubtedly imposed significant costs on Iran, but rather than triggering collapse, they have pushed the Islamic Republic toward a dual-track strategy of adaptation and escalation. Economically, Iran has pursued diversification, trade restructuring, selective import substitution, and an eastward shift in partnerships, while accelerating a de-dollarization agenda through offshore banking, digital payment systems, and alternative financial channels. These measures have helped preserve trade flows, mitigate the pressure of sanctions, and sustain core state functions. In parallel, Tehran has expanded its nuclear program both as a deterrent to further coercion and a high-stakes bargaining asset for eventual relief. While recent U.S. strikes have constrained monitored activities, Iran retains sufficient technical expertise, enriched material, and strategic ambiguity to maintain nuclear leverage. The theory of rapid collapse through “maximum pressure” has been blunted by these adaptations, even as it deepens Iran’s militarized and exclusionary economic order.

Inclusive or exclusive resistance strategy

After 12 days of war and facing further potential episodes of military confrontation with the U.S. and Israel, Iran has reframed its adaptation to sanctions and its survival strategy. In Tehran’s view, the United States is unwilling to reach a deal, as it insists on absolute surrender. In the absence of a credible diplomatic pathway, Iranian officials increasingly frame the horizon as “three difficult years,” expecting that a geopolitical shift or changes in U.S. policy after the 2028 election might ease pressure. While economic adjustments remain in place, including diversified trade channels, import substitution, and eastward integration, there is an ongoing internal debate over the nature of Iran’s resistance. Pragmatic conservatives and reformists advocate an inclusive resistance strategy that integrates security and military priorities with broader economic and social measures to diffuse hardship across society. They argue that broad-based resilience strengthens the “rally-around-the-flag” effect after the war, and enhanced social resilience and national solidarity would foster further economic resilience. On the other hand, hardline security networks tend to favor path-dependent centralization and repression. They push for an exclusive resistance strategy that relies on a narrower coalition, greater coercion, and tighter control over information, finance, and logistics. What is new in wartime is that the sanctions-era toolkit is now embedded in a security-first posture: resource allocation is faster and more centralized, tolerance for dissent narrows, and policy sequencing prioritizes continuity of core functions over efficiency.

An inclusive approach involves strengthening Iran’s resilience by mobilizing public opinion, expanding domestic support, and prioritizing the welfare of the general population, rather than just regime loyalists. Proponents of this strategy argue that, as in the Iran–Iraq War, Iran should counter economic warfare by investing in human capital and societal cohesion, thereby reducing public grievances and effectively countering U.S. pressure. For example, increasing cash transfers, food subsidies, and healthcare support can help the poorest and middle-class families withstand rampant inflation. This approach requires redirecting public resources from cultural and ideological projects toward social spending. The most challenging aspect of this inclusive strategy may be relaxing domestic repression and fostering greater pluralism to sustain societal engagement with the system. This could involve releasing certain political prisoners, easing internet censorship, tolerating mild criticism or protests, encouraging some members of the Iranian diaspora to return, and involving professional and middle-class groups in policy discussions. The logic is that by mobilizing public opinion and goodwill, the state can enhance legitimacy and reduce the appeal of any foreign-backed regime-change narratives. Inclusive resistance recognizes that Iran’s ultimate source of strength is its people; keeping them reasonably content or hopeful is a better firewall against external pressure than brute force alone. Partial liberalization, however, can trigger higher mobilization if material conditions do not improve concurrently; sequencing and credible commitment are therefore central to this pathway.

An exclusive approach to resistance focuses on regime survival by rallying a narrow base and suppressing dissent. Hardliners and the security establishment assume that any liberalization poses an existential risk, potentially weakening the regime’s grip. Instead, they argue that Iran must hunker down, prioritize resources for the military and loyalist segments of society, and suppress any signs of dissent ruthlessly until the external threat passes. This is largely the path Iran has taken since 2018. Under maximum pressure, Iran increased defense and security spending while reducing social welfare budgets. Hardliners redirected their welfare resources toward their controlled charities and organizations. For example, the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, or IRGC, and revolutionary para-governmental foundations called “bonyads” launched campaigns to distribute food packages in poor areas, portraying themselves as the people’s saviors while sidelining independent NGOs. This exclusive welfare approach means that aid is distributed in a patronage manner, to those considered loyal or to buy loyalty, rather than as a universal right. Additionally, Iran’s privilege-based welfare system ensures that the military, police, civil servants, and regime loyalists remain relatively unaffected, allowing Tehran to retain those capable of organizing a challenge or whose defection could be disastrous for them. This elite capture of welfare significantly hinders the effectiveness of sanctions in creating political pressure, as those most affected (unemployed youth, informal laborers, and rural poor) have minimal influence on state policy.

The exclusive strategy relies on tight internal control, and dissenting voices are aggressively silenced to prevent the opposition from leveraging economic grievances. The IRGC and intelligence services have cracked down on charities and NGOs that operate outside of state approval. Economically, exclusive resistance might mean steering even more of the economy into the hands of the Revolutionary Guard and other sanction-proof entities (further militarizing the economy), on the theory that these actors are reliable and experienced in running a war economy. Benefits would continue to flow to regime loyalists and the insider network, reinforcing their commitment. Meanwhile, disaffected groups might be expected to endure or be intimidated into silence. Essentially, exclusive resistance is about survival through authoritarian muscle memory, sacrificing pluralism and broad prosperity in favor of ensuring that the regime’s power centers remain intact and unchallenged.

In practice, Iran’s response will probably incorporate components of both strategies. While President Masoud Pezeshkian and Ali Larijani, the head of Iran’s National Security Council, are preparing a list of reforms, including public budget reform, further political prisoner releases, and facilitating the return of Iranian diaspora figures, the hardliners in the security establishment are actively working to obstruct their implementation. A mix of passivity, bureaucratic inefficiency, strategic ambiguity, and uncertainty about the efficacy of either approach has further stalled choice. The system’s decision-making is slow and consensus-bound, with multiple veto players; as a result, policy tends to drift, reinforcing indecision rather than enabling a clear pivot toward either an inclusive or an exclusive path.

Over a two- to three-year horizon, the balance of evidence points to adaptation rather than collapse. Iran retains a portfolio of tools that will be deployed singly or in combination. These measures raise economic costs and weaken the independent private sector, shrink the middle class, but preserve core state functions and regime cohesion. As a result, additional pressure alone is unlikely to deliver the desired outcomes over the next three years; it is more likely to deepen militarization and entrench the existing balance of power than to produce collapse or comprehensive policy surrender.

Iran’s near-term economic outlook under sanctions

Under U.N. Security Council Resolution, UNSCR, 2231, if Iran is found to be in significant noncompliance with its nuclear commitments, any participant may request the reimposition of the Iran–related UNSCRs.28These include UNSCRs 1696, 1737, 1747, 1803, 1835, and 1929, adopted from 2006 to 2010 and lifted as part of the 2015 JCPOA. They covered arms transfers, missile-related activities, enrichment-related restrictions, and certain shipping-related limits. This mechanism, known as “snapback,” would expire on Oct. 18, 2025, (the “termination day”) if 2231 remained in effect without objection; conversely, after roughly 10 years from the JCPOA’s adoption, full compliance would have terminated the earlier resolutions.

Before that window closed, the United Kingdom, France, and Germany triggered the snapback mechanism. On Aug. 28, 2025, their foreign ministers notified the U.N. Security Council that Iran was in “significant non-performance” of its JCPOA commitments, triggering a 30-day countdown to reimpose the prior measures.29As such, on Sept. 28, 2025, all UNSC resolutions and sanctions were reinstated.30However, China and Russia, joined by Iran, formally rejected the move. On Oct. 18, 2025 — the termination day under Resolution 2231 — the foreign ministers of Iran, China, and Russia wrote to the Security Council, calling the snapback “legally and procedurally flawed” and urging states not to recognize the reinstated sanctions.31On Oct. 25, 2025, they sent a joint letter to the IAEA asserting that JCPOA–related verification and monitoring had ended with the expiration of UNSCR 2231 on Oct. 18. Despite this legal dispute, what matters now is the enforcement landscape and its economic consequences.

In practical terms, the economic impact of the U.N.’s snapback sanctions is modest compared to the expansive U.S. primary and secondary sanctions already constraining Iran’s oil, non-oil trade, and financial channels — especially when China and Russia, two permanent members of the UNSC, openly reject the sanctions. The adverse effects of U.N. sanctions reinforce multilateral legal risk, amplify uncertainty, worsen Iran’s existing macroeconomic fragilities, and thereby increase the effective force of U.S. sanctions.

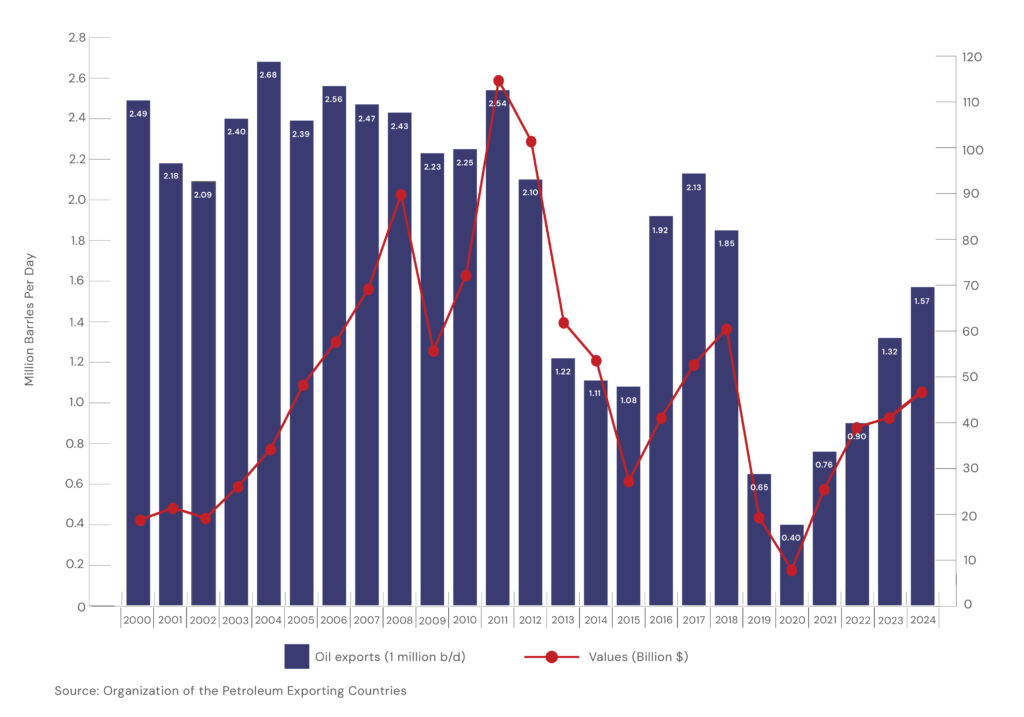

From 2006 to 2011, U.N. sanctions alone did not entirely curtail Iran’s oil receipts. Even under UNSCR 1929, Iran amassed roughly $243 billion in cumulative oil export revenue from 2009 to 2011, the highest three-year total on record.32The sharp decline in oil exports followed the tightening of U.S. secondary sanctions in 2012 and their reimposition in 2018. European trade flows also fell sharply after the U.S. withdrawal from the JCPOA, prompting many E.U. firms to exit the Iranian market in 2018. In this setting, U.N. snapback adds limited additional economic pressure while mainly reinforcing multilateral legal risk, political isolation, and uncertainty.

Figure 1. Iran’s Crude Oil Exports

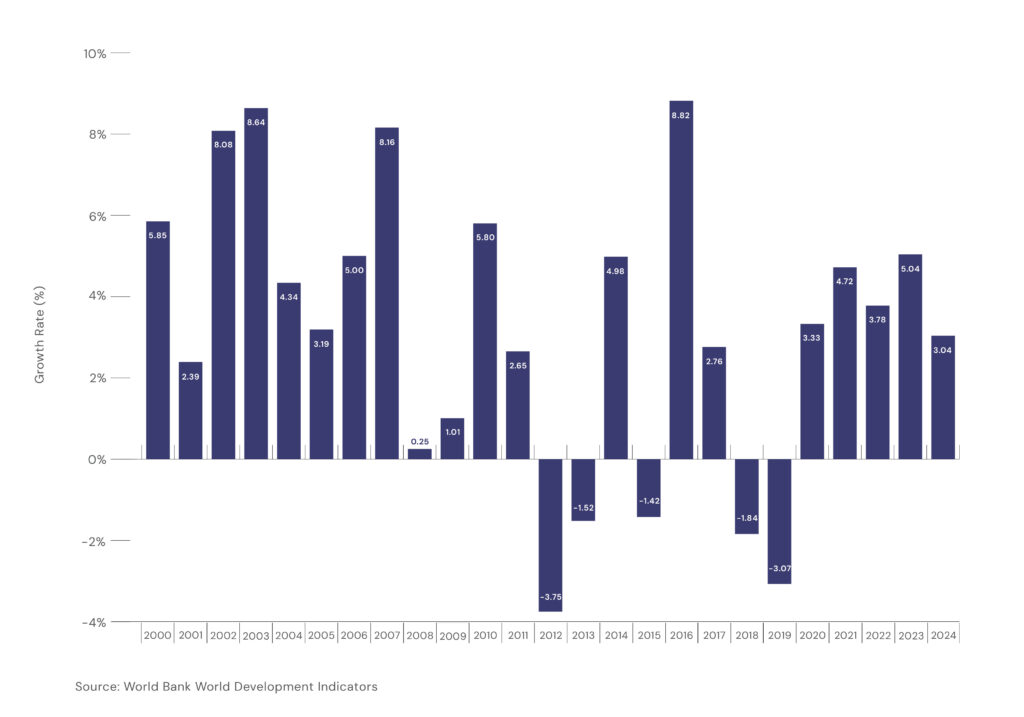

Figure 2. Iran’s GDP Growth (Annual %)

More than 2,800 U.S. designations have increasingly isolated Iran from the international financial system, shipping, insurance, and energy services.33The absence of prospects for a diplomatic solution and the looming threat of war heighten uncertainty and intensify the impact of U.S. sanctions. From 2011 to 2024, Iran’s average economic growth rate was nearly 2 percent. Insufficient investment causes capital depreciation to exceed capital formation, thereby reducing the total capital stock and hindering growth. Iran faces severe energy shortages due to inadequate investment in its energy infrastructure, leading to frequent economic shutdowns. To address its urgent needs, Iran’s economy requires at least $350 billion in investments across its energy and industry sectors.34 The devaluation of the currency, combined with a high public budget deficit, has fueled inflation.35In this context, the threat of war, heightened by Israeli rhetoric and U.S. warnings, worsens the adverse effects of U.S. sanctions. Therefore, the economic damage in the post–JCPOA era will be mainly driven by the widespread uncertainty, risk aversion, and panic that it creates in Iran’s markets and society.

Despite the severity of the economic hardship, the sanctions’ adverse effects will not cause Iran’s economy to collapse. Instead, Iran is likely to face pressure similar to that in 2018–2020, when Trump’s maximum-pressure sanctions coincided with the pandemic.

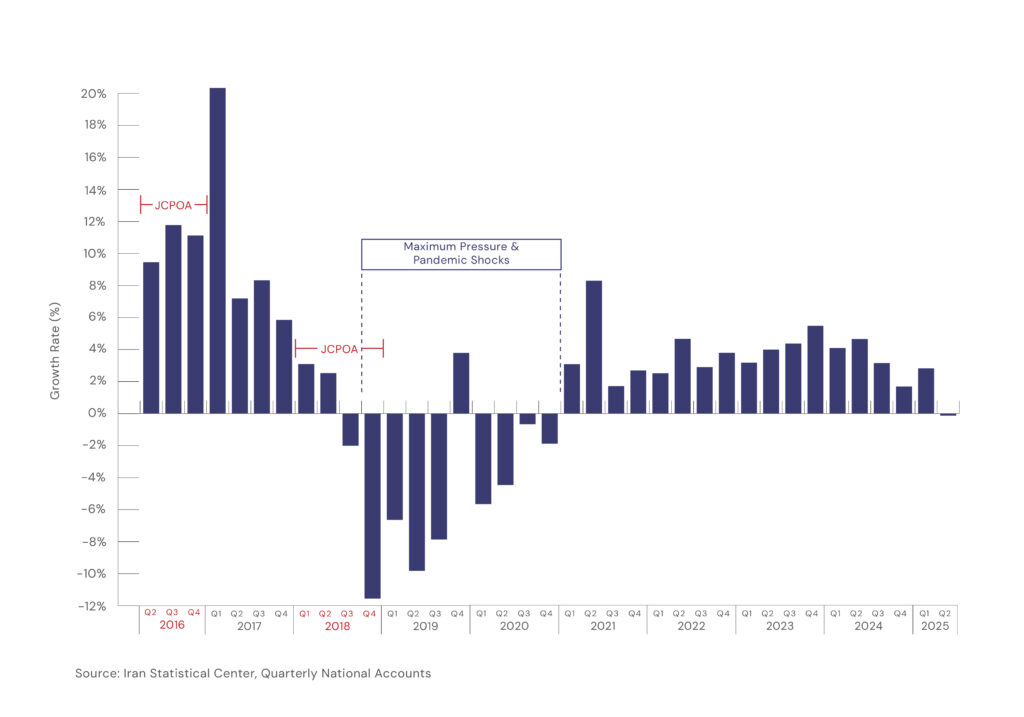

Figure 3. Iran’s Quarterly Economic Growth

Analyzing Iran’s quarterly national accounts data during Trump’s maximum-pressure campaign, from the third quarter of 2018 to the second quarter of 2020, indicates that Iran’s economy contracted by approximately 12.5 percent.36 The leading cause of the contraction was disruptions to oil exports.37Oil revenues decreased from approximately $52 billion in 2017 to $8 billion in 2020.38However, as the economy adapted through import compression, supplier diversification, increased oil exports, and greater reliance on domestic capacity, it grew by 14.5 percent from 2021 to 2024.39

Looking ahead, a repeat of the 2018–19 oil-sector collapse is less likely. The growth dynamics are therefore more likely to be determined by non-oil sectors rather than by a renewed collapse in oil output. While oil remains prominent in the macroeconomic landscape through the budget and balance of payments, prolonged sanctions have accelerated the development of ways to bypass restrictions. These include shadow fleets, regional pipeline routes, and buyer networks, which help sustain crude liftings, albeit at discounted prices. Iran’s economy’s principal vulnerabilities lie in industry (including manufacturing), construction, and services, which together account for roughly 62 to 65 percent of the economy.40These sectors face binding constraints stemming from weak investment, aging capital stock, energy shortages, and limited access to hard currency for critical intermediate and capital goods. Under the present impasse, neither war nor reconciliation, the renewed maximum-pressure campaign would likely contract Iran’s economy by about 5 to 7 percent by 2027. 41

As with previous microeconomic shocks, the most immediate consequence is an escalation in inflation. Low economic growth, coupled with limited resources, financial constraints, and increased transaction costs, would exert additional pressure on the public budget. Since 2018, a substantial public budget deficit of 20 percent to 30 percent has forced the government to implement antigrowth tax policies and raise taxes on the private sector.42Additionally, the government has resorted to borrowing from the central bank, which prints money and fuels inflation. At the same time, a hard currency shortage encourages households and firms to buy dollars and gold to protect their savings, which puts more pressure on the rial and raises the cost of imported goods. If conditions follow the shift seen after 2018, when average inflation rose from about 20 percent to roughly 35 percent, a further increase is possible.43Without a credible plan to narrow the budget deficit, reduce losses in state-linked funds and companies, and stabilize the currency market, inflation could move toward the 50 to 60 percent range while economic growth remains weak.

In the current stalemate, with neither war nor reconciliation, and lacking a comprehensive agreement or significant, costly military confrontation between Iran and the United States, the most likely scenario is a sharp two- to three-year economic stagflation, echoing 2018–2020: the state will have sufficient resources to sustain essential governance functions, even as living standards and private-sector investment remain under pressure.

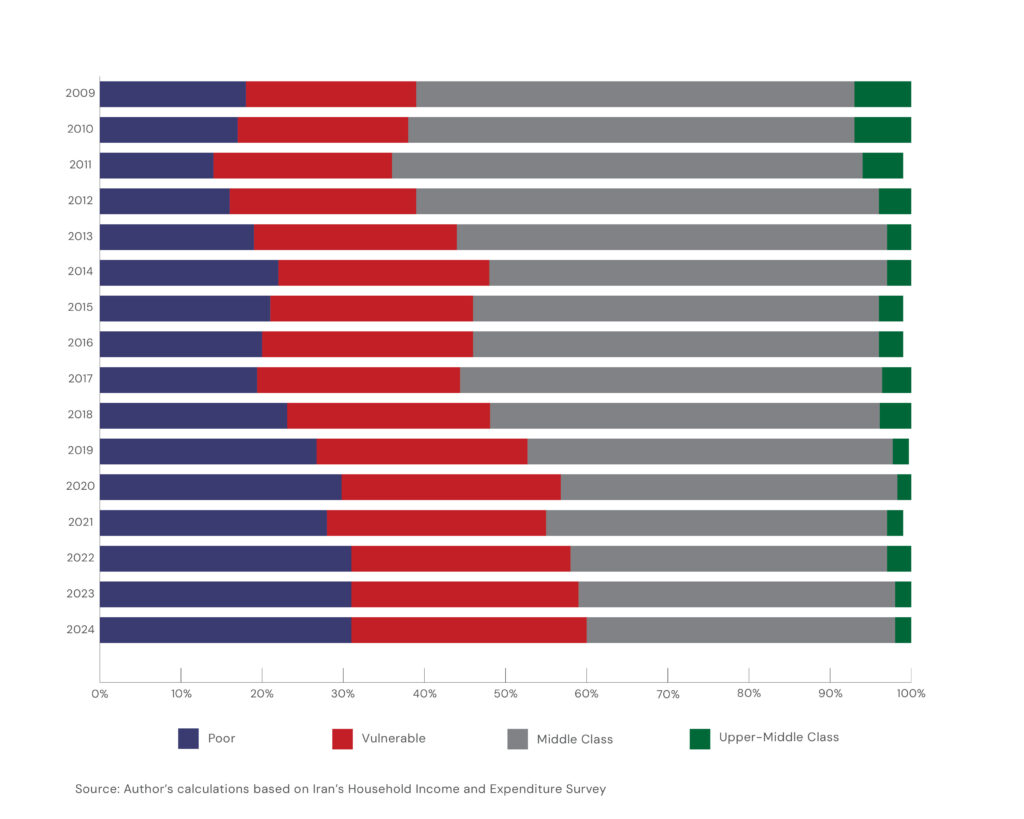

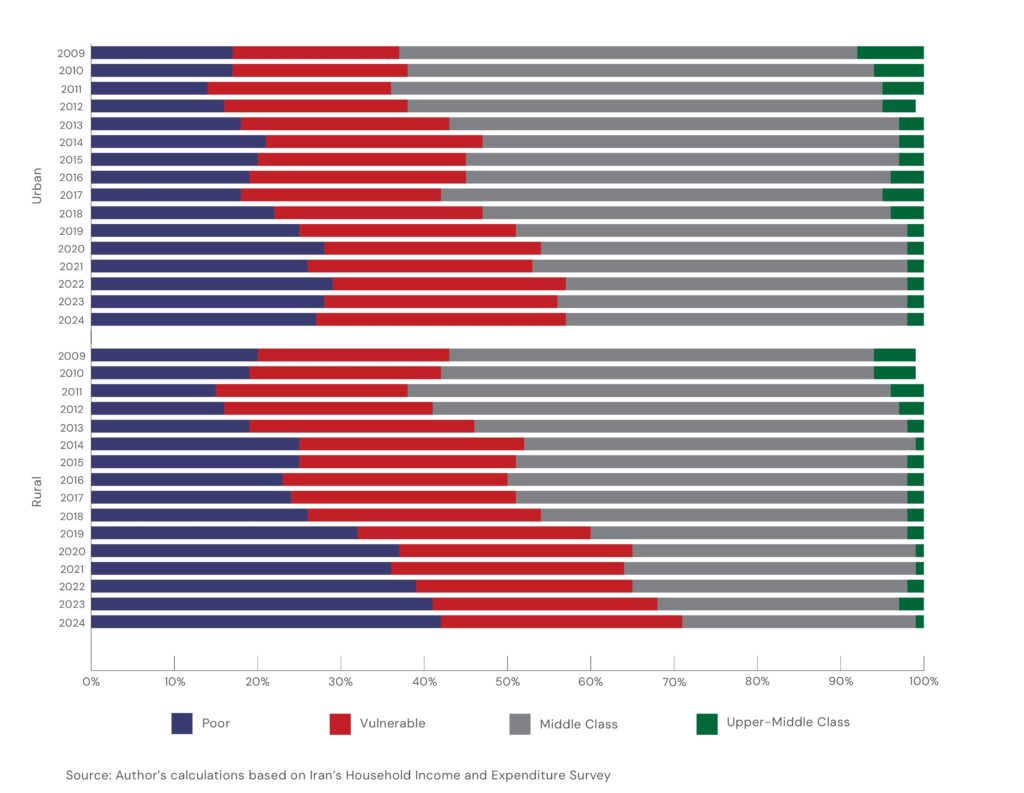

Figure 4. Distribution of Iran’s Economic Classes, 2009–2024

The welfare costs of sanctions: High pain, low gain

Perhaps most telling is the toll on Iranian households. From 2018 to 2020, poverty and economic hardship surged: The national poverty rate rose from roughly 19 percent to over 30 percent, meaning that “maximum pressure,” compounded by the pandemic, dragged more than 10 million Iranians into poverty.44Iranian average living standards declined by approximately 14.5 percent in urban areas and 18.5 percent in rural areas. While the middle class shrank by 11 percent, dropping from 52 percent to 41 percent, the share of Iranians who were poor or at risk of poverty rose from 44 percent to 56 percent from 2017 to 2020.45

In the first year of sanctions (2018–19), total employment remained steady or even increased slightly, as the sharp devaluation made domestic production relatively cheaper and encouraged import substitution in manufacturing and agriculture. Formal employment appeared “resilient under sanctions,” in part because labor-market rigidities limited layoffs and real wages adjusted downward. The more severe employment shock arrived with COVID–19: from March 2020 to March 2021, the economy lost approximately 1.1 million jobs, with more than 60 percent of these jobs held by women.46However, following a modest growth from 2021 to 2024, employment regained roughly 1.2 million jobs lost during the pandemic.

Figure 5. Urban vs. Rural Distribution of Iran’s Economic Classes,

2009–2024

These economic gains, however, did not translate into a broad-based reduction in poverty. Poverty remained at nearly 30 percent in 2024, with more than 60 percent of the population being poor or at risk of poverty.47The middle class also contracted further, from 41 percent to 38 percent from 2020 to 2024. It is worth mentioning that Iran’s middle class comprised nearly 60 percent of the population in 2011; a decade of sanctions has compressed it to about 38 percent, dragging more than 20 percent of Iranians into poverty or vulnerability, without precipitating either regime collapse or an outright economic breakdown.

Looking ahead, a replication of the 2018–2020 experience can be anticipated for 2025–27. If this is the case, we can expect the number of poor and vulnerable individuals to rise by an additional 10 million. This means that the number of those who are poor or vulnerable could rise up to 70 percent, and the middle class would shrink by about 10 percent, to roughly 25 to 28 percent of the population. However, owing to the uneven distribution of adverse impacts on households, the most voiceless part of the population would suffer the most.

As one of the unintended consequences of the sanctions, Iran’s welfare state has evolved into a privilege-based system that disproportionately shields public employees and politically connected groups while leaving the informal majority exposed.48While all households have suffered economic contractions, particularly in healthcare, education, transportation, and leisure expenditures, public employees have experienced significantly fewer welfare losses than informal-sector workers. This disparity underscores the political economy of social protection in Iran, where government employees, as key actors in maintaining state functions, are shielded from the adverse impact of economic downturns.

A review of Iran’s public budget in fiscal year 2025 (March 2025 to March 2026) shows that roughly 45 percent of total public spending is labeled as “welfare.”49Nearly half of this welfare budget is allocated to public employees and retirees, who make up only about a quarter of the population. On average, a public employee draws roughly triple the per capita welfare resources available to everyone else. Beyond these visible allocations, a “hidden welfare state” of agency cooperatives, subsidized loans, exclusive lodging and recreation, and off-budget benefits further insulates public servants, especially those in the security and military apparatus. By contrast, informal workers face thinner social insurance, patchy assistance, and far less institutional leverage over policy choices. While public employees spend about 1.5 times more than the average household and twice as much as those led by informal workers, the poverty rate among informal workers is seven times higher than that of public workers.50

In practice, economic sanctions deplete the state’s resources and force it to focus more on system-supporting groups, further widening the insider-outsider gap. This particular bias fosters resilience within the ruling group. By protecting core cadres through both visible and hidden welfare channels, the system absorbs external shocks, shifting the heaviest burden of sanctions onto the politically less-connected majority. As such, low-influence informal workers bear the brunt of economic shocks, permitting the regime to survive at the cost of the broader population.

Costs and risks for U.S. policy

The findings above demonstrate that the renewed U.S. pressure campaign, backed by sanctions and the threat of force, is unlikely to deliver capitulation. The Islamic Republic has demonstrated economic resilience by shifting trade eastward, using shadow fleets to transport oil, replacing some imports, and channeling payments outside U.S. control. These adoption tools blunt rather than neutralize the impact of sanctions, allowing the political system to endure and continue functioning. In the absence of a diplomatic path based on mutual compromise, intensified pressure will prolong hardship and stagnation for Iranians; however, it is unlikely to result in collapse or meaningful concessions. Instead, the pressure-first approach could increase the risk of miscalculation, prolonged tension, and unintended escalation. As pressure intensifies and Iran remains resistant, Washington’s perceived options are likely to increasingly shift toward the use of force. Tehran, in turn, may further leverage nuclear ambiguity to navigate external pressures. When exposed to sustained and exceptional pressure, Tehran may seem more susceptible; however, this perceived vulnerability risks being misinterpreted, potentially intensifying advocacy for military intervention as validation.

A cost-effective approach first recognizes the limits of a pressure-only policy. The insulting rhetoric of calling for unconditional surrender and any acceptance of maximal demands under duress raises domestic political costs and undermines the legitimacy of compromise in Tehran, shrinking the space for de-escalation. Absent a credible diplomatic pathway based on compromise rather than maximalist demands from either side, the most likely trajectory is costly adaptation in Iran and rising escalation risk for Washington, rather than capitulation or collapse. For Washington, the implication is clear: If it seeks to avoid another major Middle East war, the pursuit of maximum pressure to achieve maximalist goals is unlikely to deliver that. Rather, pressure must be coupled with a realistic diplomatic track that limits Iran’s nuclear activities in return for economic relief. In practice, this means shifting from a strategy of forced capitulation to one of risk management that contains Iran’s nuclear program at a lower cost and with fewer escalation risks.

Conclusion

Tehran is trapped in a strategic deadlock as the Trump administration appears to seek capitulation rather than a credible path to compromise with Washington. Further escalation risks a war that could topple the regime, albeit at immense regional cost. In this situation, resistance is not a strategic preference, but the only perceivable option. Washington’s humiliating rhetoric of unconditional surrender reinforces the perception in Tehran that the real U.S. goal is regime change, making political compromise domestically toxic. For the Islamic Republic, conceding under duress would validate fears of regime change, erode domestic legitimacy, and embolden adversaries. With no trust in U.S. intentions and no viable off-ramp, Tehran sees absorbing economic pain as the only way to preserve deterrence and wait out a change in Washington. In this context, Iran is likely to repeat the pattern seen from 2018 to 2020: costly adaptation rather than capitulation. The Islamic Republic has already demonstrated its ability to endure pressure through a combination of institutional insulation, macroeconomic adjustment, and political consolidation. Sanctions have inflicted significant harm, particularly on the poor and informal sectors. At the same time, its privileged welfare system shields insiders, allowing it to retain the administrative capacity and coercive tools necessary for regime preservation.

Absent a comprehensive diplomatic breakthrough or a full-scale military confrontation, the most plausible trajectory is two to three years of stagflation, high inflation, and sluggish growth. Real incomes are likely to erode further, pushing more households below vulnerability thresholds, shrinking the middle class, and reducing the space for private investment or an inclusive recovery. The result will be heightened social and economic strain, but not systemic collapse.

With broad concessions on resistance strategy, there is ongoing internal debate over inclusive versus exclusive resistance strategies that reflect more tactical differences than a rethinking of core principles. Although modest reform proposals have surfaced, including selective political liberalization and expanded social support, there is little evidence that the security establishment will permit shifts that jeopardize regime control.

Without a credible diplomatic way out or a major internal crisis, the pressure campaign’s basic assumptions will likely prove wrong. Instead of forcing a surrender or collapse, it will merely prolong suffering, weaken the middle class, and enhance authoritarian resilience. As before, those with the least political influence will suffer the most, and the regime will survive, not despite sanctions, but because of how it unevenly distributes its costs. For Washington, a pressure-driven approach will not alter Iran’s calculus, but it will deepen the very dynamics that have long undermined U.S. interests and goals.

Program

Entities

Citations

Gareth Porter, “Iran Proposal to U.S. Offered Peace with Israel,” Antiwar.com, May 25, 2006, https://original.antiwar.com/porter/2006/05/25/iran-proposal-to-us-offered-peace-with-israel/. ↩

Karen Freifeld, “Trump Says He Sent Letter to Iran Leader to Negotiate Nuclear Deal,” Reuters, March 7, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/world/trump-says-he-sent-letter-iran-leader-negotiate-nuclear-deal-2025-03-07/. ↩

Seyed Abbas Araghchi, “Iran’s Foreign Minister: The Ball Is in America’s Court,” Washington Post, April 8, 2025, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2025/04/08/iran-indirect-negotiations-united-states/. ↩

Karen Freifeld, “Trump Urges Tehran Evacuation as Iran–Israel Conflict Enters Fifth Day,” Reuters, June 17, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/business/aerospace-defense/trump-urges-tehran-evacuation-iran-israel-conflict-enters-fifth-day-2025-06-17/. ↩

Tucker Carlson, “Interview with Iranian President Masoud Pezeshkian,” Tucker Carlson Network, September 2024, https://tuckercarlson.com/iran-interview. ↩

“Netanyahu Hails ‘Unmatched’ Coordination with U.S. Prez Trump during Washington Visit over Gaza Deal,” ANI News, July 8, 2025, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=w_HnpzQIsS8. ↩

“In Recording, Netanyahu Boasts Israel Convinced Trump to Quit Iran Nuclear Deal,” The Times of Israel, July 17, 2019, https://www.timesofisrael.com/in-recording-netanyahu-boasts-israel-convinced-trump-to-quit-iran-nuclear-deal/. ↩

Esfandyar Batmanghelidj, “Resistance Is Simple, Resilience Is Complex: Sanctions and the Composition of Iranian Trade,” Middle East Development Journal 16, no. 2 (2024): 220–238, https://doi.org/10.1080/17938120.2024.2417624. ↩

Batmanghelidj, “Resistance Is Simple.” ↩

Timothy Gardner and Ismail Shakil, “U.S. Imposes Iran–Related Sanctions on Third China ‘Teapot’ Refinery and Ports,” Reuters, May 8, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/us-imposes-iran-related-sanctions-third-china-teapot-refinery-ports-2025-05-08/. ↩

Laurence Norman and James T. Areddy, “How China Secretly Pays Iran for Oil and Avoids U.S. Sanctions,” Wall Street Journal, June 24, 2024, https://www.wsj.com/world/middle-east/how-china-secretly-pays-iran-for-oil-and-avoids-u-s-sanctions-b6f1b71e. ↩

U.S. Department of the Treasury, “Treasury Targets Iranian Network Evading Sanctions and Enabling Oppression,” news release, Nov. 25, 2024, https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/sb0220. ↩

U.S. Library of Congress. Congressional Research Service. Central Bank Digital Currencies, by Marc Labonte and Rebecca M. Nelson. IF11471. 2024, https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/IF11471. ↩

Kosta Gushterov, “Iran Ready to Use Digital Currency to Fight Western Sanctions,” CryptoDnes, Nov. 27, 2024, https://cryptodnes.bg/en/iran-ready-to-use-digital-currency-to-fight-western-sanctions/. ↩

“Iran Unveils SWIFT Competitor Called ACUMER,” bne IntelliNews, Nov. 26, 2024, https://www.intellinews.com/iran-unveils-swift-competitor-called-acumer-354944/. ↩

“ACU Says to Unveil SWIFT Alternative,” Financial Tribune, Nov. 25, 2024, https://financialtribune.com/articles/business-and-markets/118272/acu-says-to-unveil-swift-alternative. ↩

“Iran Makes First Import Order Using Cryptocurrency,” Middle East Monitor, Aug. 9, 2022, https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/20220809-iran-makes-first-import-order-using-cryptocurrency. ↩

“Iran and Russia Link Banking Systems amid Western Sanctions,” Reuters, Jan. 30, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/business/finance/iran-russia-link-banking-systems-amid-western-sanction-2023-01-30. ↩

Genevieve Donnellon-May, “Israeli Strikes One More Challenge for New China–Iran Rail Corridor,” South China Morning Post, Oct. 18, 2024, https://www.scmp.com/opinion/china-opinion/article/3314468/israeli-strikes-one-more-challenge-new-china-iran-rail-corridor. ↩

“Tehran, Moscow to Finalize INSTC Rail Project Next Month,” Al Mayadeen English, Oct. 19, 2024, https://english.almayadeen.net/news/Economy/tehran–moscow-to-finalize-instc-rail-project-next-month ↩

“۳۲۰ تولیدکننده ماده اولیه دارو: عمق تولید باید افزایش یابد [Pharmaceutical Raw Material Producers: Production Depth Must Increase],” Tasnim News Agency, May 12, 2025, https://www.tasnimnews.com/fa/news/1404/02/23/3312041/320-تولیدکننده-ماده-اولیه-دارو-عمق-تولید-باید-افزایش-یابد. ↩

Batmanghelidj, “Resistance Is Simple.” ↩

Ian Traynor and Kasra Naji, “Tehran Agrees to Nuclear Freeze,” The Guardian, Nov. 8, 2004, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2004/nov/08/politics.eu. ↩

Esther Pan, “Iran: Nuclear Negotiations,” Council on Foreign Relations, updated Feb. 22, 2024, https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/iran-european-nuclear-negotiations. ↩

“Iran Claims Nuclear Breakthrough,” The Guardian, April 11, 2006, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2006/apr/11/iran; Seyed Hossein Mousavian, The Iranian Nuclear Crisis: A Memoir (Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press, 2012). ↩

Sahar Nowrouzzadeh and Daniel Poneman, “The Deal That Got Away: The 2009 Nuclear Fuel Swap with Iran,” Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, Harvard Kennedy School, 2021, https://www.belfercenter.org/publication/deal-got-away-2009-nuclear-fuel-swap-iran. ↩

Hadi Kahalzadeh, “The Economic Dimensions of a Better Iran Deal,” Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft, July 24, 2025, https://quincyinst.org/research/the-economic-dimensions-of-a-better-iran-deal/; Ben Hubbard, Palko Karasz, and Stanley Reed, “Two Major Saudi Oil Installations Hit by Drone Strike, and U.S. Blames Iran,” New York Times, Sep. 14, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/09/14/world/middleeast/saudi-arabia-refineries-drone-attack.html. ↩

United Nations Security Council, “Background on Security Council Resolution 2231 (2015) on Iran Nuclear Issue,” https://main.un.org/securitycouncil/en/content/2231/background. ↩

United Kingdom Foreign, Commonwealth, & Development Office, “Iran Nuclear Snapback: E3 Foreign Ministers’ Letter,” Aug. 28, 2025,” https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/68b06156fef950b0909c1787/Iran-nuclear-snapback-E3-foreign-ministers-letter-28-August-2025.pdf. ↩

United States Department of State, “Completion of U.N. Sanctions Snapback on Iran,” news release, Sept. 27, 2025, https://www.state.gov/releases/office-of-the-spokesperson/2025/09/completion-of-un-sanctions-snapback-on-iran. ↩

“Iran, China, Russia Declare UNSCR 2231 Expired,” Tasnim News, Oct. 19, 2025, https://www.tasnimnews.com/en/news/2025/10/19/3426773/iran-china-russia-declare-unscr-2231-expired. ↩

Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries, Annual Statistical Bulletin 2023, 2024, https://publications.opec.org/asb/archive/chapter/108/1604/1611. ↩

Author’s estimates based on data from the Office of Foreign Assets Control List Search Tool. See: U.S. Department of the Treasury, “Sanctions List Search Tool,” https://sanctionssearch.ofac.treas.gov/. ↩

Kahalzadeh, “Economic Dimensions.” ↩

The national currency has devalued from approximately IRR 11,000 per USD in December 2011 to approximately IRR 110,000 per USD by October 2025, fueling rises in inflation, increasing the average rate from roughly 20 percent over nearly three decades to around 40 percent since 2018. ↩

Author’s estimates, based on Iran’s quarterly national accounts data, Iran Statistical Center, 2000–2025. ↩

Analyzing Iran’s quarterly national accounts data from July 2018 to June 2020 indicates that the value added in oil and mining declined by approximately 43 percent and 40 percent, respectively. ↩

OPEC, Annual Statistical Bulletin 2023. ↩

World Bank Group, “GDP Growth (Annual %): Iran, Islamic Rep.,” last updated 2025, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.KD.ZG?end=2023&locations=IR&start=2010. ↩

Author’s estimates, based on Iran’s quarterly national accounts data, Iran Statistical Center, 2000–2025. ↩

World Bank Group, “Signs of Improvement in the Economic Outlook for the Middle East, North Africa, Afghanistan, and Pakistan Region,” Oct. 7, 2025, https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2025/10/07/signs-of-improvement-in-the-economic-outlook-for-the-middle-east-north-africa-afghanistan-pakistan-region. This study predicts that the economy could contract by up to 5 to 7 percent from 2025 to 2027. Following the imposition of U.S. secondary sanctions in 2012, the industry experienced its worst contraction, recorded at approximately 10 percent. During periods of macroeconomic shock, services typically declined by up to 3.5 percent. If agriculture and oil output remain broadly flat while services decline by 3.5 percent, industry excluding oil by 10 percent, and construction by 24 percent (matching their worst post-2010 outcomes), standard value-added weights imply a headline real–GDP contraction of roughly 4.5 to 5 percent in 2025 and 2026. If these sectoral declines do not repeat, growth in 2027 could likely stabilize around 0 to +1 percent. By contrast, a cumulative decline in the range of 5 to 7 percent is expected by 2027. The most recent World Bank forecast, following the 12-day conflict, predicts that Iran’s economy will shrink by 1.7 percent in 2025 and by 2.8 percent in 2026. ↩

Author’s estimates, based on the budget-liquidation reports of the Supreme Audit Court of Iran. See: Supreme Audit Court of Iran, 1398–1402 [2019/20–2023/24], https://dmk.ir/fa/page/103506-تفریغ-بودجه.html. ↩

World Bank Group, “Inflation, Consumer Prices (Annual %): Iran, Islamic Rep.,” last updated 2025, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/FP.CPI.TOTL.ZG?locations=IR. ↩

This study estimates poverty by the Cost of Basic Needs method and with Iranian Household Expenditure and Income Survey data (1378–1403). The food poverty line is the cost of a 2,100-kcal diet per adult-equivalent, calculated separately for urban and rural areas in each province for 1388–1403. The total poverty line is obtained by multiplying the food line by the inverse of the Engel coefficient estimated from households whose per capita food spending lies within ±5 percent of the food line. Households are considered poor if their per-adult-equivalent expenditure is below the poverty line; vulnerable if it is between 100 to 150 percent of the poverty line; middle class if it is between 150 to 500 percent of the poverty line; and upper-middle class if it is above 500 percent of the poverty line. ↩

Author’s estimates, based on the Iranian Household Expenditure and Income Survey, Raw Data, Iran Statistical Center, 1378–1403 [1999/2000–2024/25], https://amar.org.ir/english/Statistics-by-Topic/Household-Expenditure-and-Income#2220530-releases. ↩

Author’s estimates, based on the Iranian Labor Force Survey, Statistical Center of Iran, 1390–1403 [2011/12–2024/25], https://amar.org.ir/statistical-information/catid/30rate rate 50/types/7. ↩

(( World Bank’s estimation of the international poverty line ($4.20/day, 2021 PPP) suggests a decline in Iran’s poverty from about 12 percent in 2020 to 8 percent in 2023. See: Word Bank Group, “Poverty Headcount Ratio at $4.20 a Day (2021 PPP) (% of Population): Iran, Islamic Rep.,” last updated 2025, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SI.POV.LMIC?locations=IR. ↩

Hadi Kahalzadeh, “Civilian Pain without a Significant Political Gain: An Overview of Iran’s Welfare System and Economic Sanctions,” Rethinking Iran (SAIS), 2023, https://www.rethinkingiran.com/iran-sanctions-reports/. ↩

Author’s estimates, based on Iran’s Public Budget Law for FY 1404 (March 2025–March 2026), Islamic Consultative Assembly (Majlis) Research Center, https://rc.majlis.ir/fa/law/show/1828222. ↩

Author’s estimates, based on the Iranian Household Expenditure and Income Survey, Raw Data, Iran Statistical Center, 1378–1403 [1999/2000–2024/25], https://amar.org.ir/english/Statistics-by-Topic/Household-Expenditure-and-Income#2220530-releases. ↩