Opportunity for a Europe–China Reset?

On March 24, 2025, the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft and the Geneva Centre for Security Policy co-convened a Track II roundtable discussion between European and Chinese experts. The purpose of the roundtable was to explore the extent to which Europe and China have overlapping interests — and therefore share potential for cooperation — in the context of the ongoing Ukraine ceasefire negotiations and whether such cooperation could lead to a broader reset between Beijing and European capitals. This document is a summary of the roundtable discussion.

A strained relationship

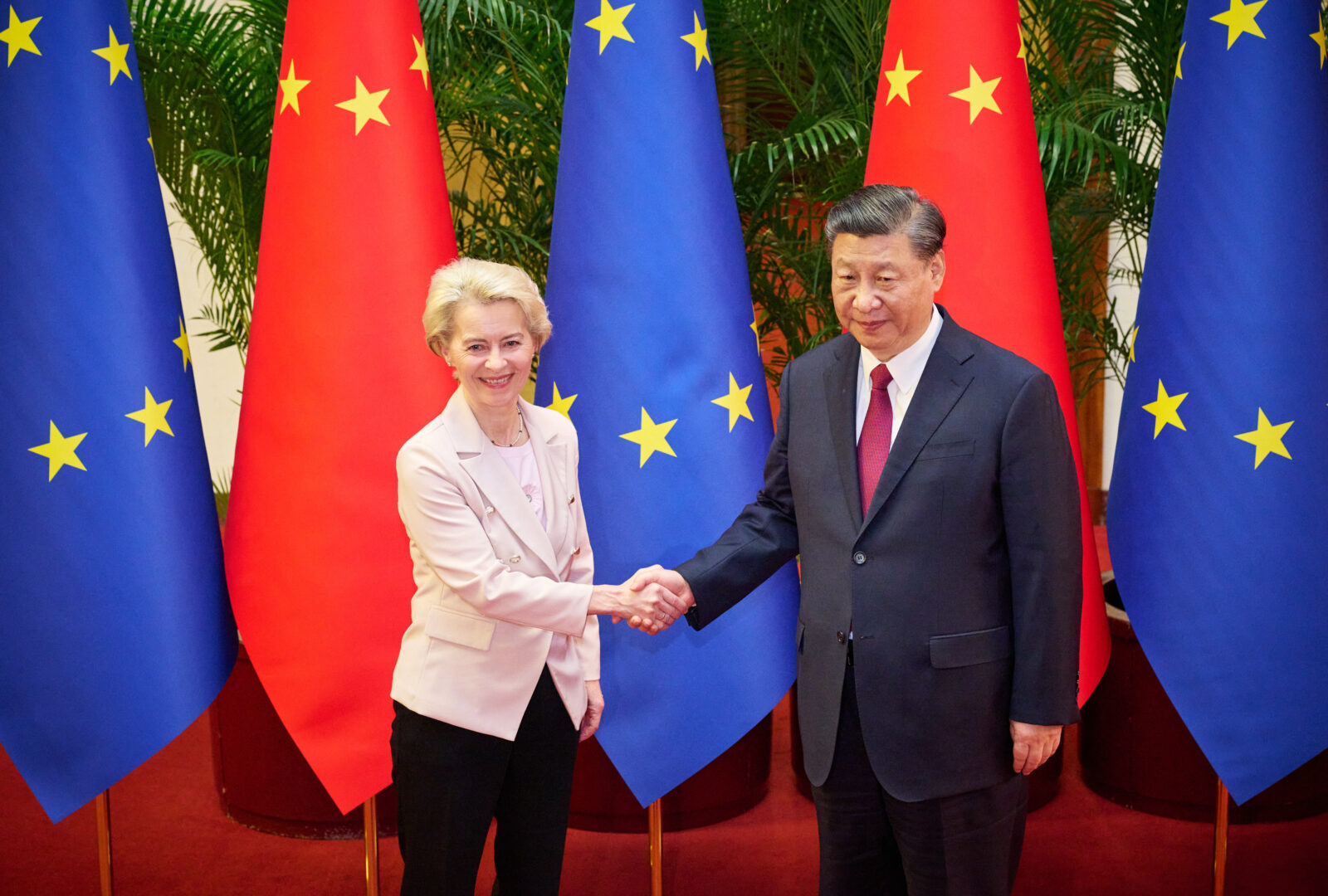

Relations between the European Union and China have visibly soured in recent years. Already in 2019, three years before Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the European Commission had begun referring to China as a “systemic rival.” Bilateral ties then took a more significant nosedive when reciprocal sanctions were imposed in 2021, with Beijing’s retaliatory moves standing out for targeting a European think tank and members of the European Parliament, or MEPs. Commission President Ursula von der Leyen’s 2023 speech calling for a “de-risking” strategy set a somber tone for the future of the E.U.–China relationship.

Yet, as the Biden administration has given way to a tariff-friendly second Trump administration — and ideological bipolarity has been replaced with gradual acceptance of multipolarity — might Europe and China begin to recalculate their interests? Many E.U. member states, already feeling the impact of the rupture in relations with Russia, are wary of engendering further economic turmoil if geopolitical inertia leads to a further fraying of ties with China. Beijing’s recent decision to lift the sanctions it had imposed on MEPs creates the opportunity for a thaw, but the general direction of travel of the past several years will remain difficult to reverse, in part because both sides may not view the need to seize the opportunity to restore more substantive ties with the same degree of urgency.

European participants in our Track II discussion conjectured that China may settle for merely maintaining the current level of economic and political engagement with Europe, given that Europe continues to provide China with access to technology that it can no longer obtain from the United States. However, Chinese participants suggested that this may not be sufficient; their hope was for China to be accepted as an equal shaper of the terms of the global economic order alongside Europe and the United States. If this does not occur, the participants said there is a risk that China will turn inward, with negative implications for both Asia’s security order and global stability more generally.

Some participants suggested that reviving the E.U.–China Comprehensive Agreement on Investment, or the CAI, may offer a pathway forward — with the aim of either updating some of its components in advance of ratification or salvaging those aspects that remain the most feasible. A high-level E.U.–China summit also looms in July, which offers the opportunity for a broader economic reset. In this context, Brussels and Beijing could ensure that any deals they strike in response to President Trump’s trade agenda conform to the World Trade Organization’s Most-Favored Nation rules as a means of shoring up the foundations of a predictable multilateral trading order.

However, such moves, while worthwhile, may run up against significant political obstacles; not only because of existing E.U.–China bilateral disputes but also due to the broader “democracy vs. autocracy” narrative that has taken root in Europe since the CAI was put on ice in 2021 — before Russia had launched its war of aggression. As an illustration of this narrative’s staying power, India continues to be seen in a positive light in European elite circles, even though it still pursues defense cooperation with Russia.

It remains to be seen if the United States under Donald Trump wishes to create the conditions for an E.U.–China thaw as a means of empowering Europe to become a more strategically autonomous pole capable of carrying more of the security burden in a multipolar world. If so, Washington may consider assuaging European security concerns by communicating clearly that it does not seek to engineer a “reverse Kissinger” to align with Moscow against Beijing. Europeans worry that such a development would allow Russia to exercise more leverage over China, strengthening the former and allowing it to pose more of a threat to Europe. Washington should make clear that President Nixon was exploiting already-existing tensions between Moscow and Beijing — tensions that do not exist today — and that its goals are limited to pursuing détente.

Shared interests in Ukraine?

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has left it increasingly dependent on China, giving Beijing a potentially important role in shaping an end to hostilities. However, the perception that China has chosen Russia’s side in an escalating conflict between Moscow and the West has made European policy audiences wary of granting it too great a role in Ukraine’s ceasefire negotiations and post-conflict landscape. That said, with European governments having cut their economic and diplomatic ties with Russia and under pressure from the Trump administration to increase their defense spending, it remains an open question whether Europe can carry the entire burden of conflict resolution and reconstruction in Ukraine.

Yet, despite the simultaneous pressure that Europe and China are feeling from the Trump administration, thus far we have not witnessed any visible thaw in relations that could contribute to filling in the varied pieces of the Russia–Ukraine puzzle. A sizable portion of the European elite continues to view China’s growing influence as a challenge that includes security implications. China, for its part, remains wary of tying itself to — and expending its political capital on — a negotiations process in Ukraine that may fail.

Chinese participants in the discussion emphasized that, while China may have the ability to engage with Russia to discourage it from using nuclear weapons in Ukraine, it does not have sufficient leverage to bring the belligerents to the table to reach a negotiated settlement. While China put forward its own 12-point peace plan in 2023 and a six-point plan alongside Brazil in 2024, these measures were taken in response to international pressure and were not an indication of Beijing’s ability to serve as an active mediator. Similarly, its participation in the “Friends for Peace” grouping offers Beijing a strategic means of insulating its position on Ukraine amid a broader — and more under-the-radar — Global South coalition.

China has in fact been struggling to define its position regarding the war in Ukraine. Beijing’s reticence toward taking on a more active role owes itself partly to the fact that it does not wish to expose itself, given its lack of experience as a mediator to date. Although China wants to be seen as a stabilizing force, adopting a higher profile in conflict mediation and post-conflict security arrangements would represent a major “diplomatic leap forward,” which it is probably not yet ready for. Beijing’s role in normalizing relations between Tehran and Riyadh, for instance, was not as the initiator of the process but rather limited mostly to “clinching the deal.”

Chinese participants further asserted that, since it is not a direct participant in the conflict, Beijing does not have the same ability to exert economic leverage over Russia as it does, say, over the Philippines. In fact, from Beijing’s perspective, the West often overestimates China’s economic influence over Russia more generally. And while it may be open to sending peacekeepers to Ukraine once the parameters of such a mission are defined, Beijing is also cognizant of the negative imagery that could be associated with the presence of Chinese troops on European soil, given current tensions between China and the West. It was therefore suggested that Europeans may wish to provide Beijing with incentives to garner its more active support for restoring stability in Europe.

One area where China could contribute, according to Chinese interlocutors, was in expediting the reconstruction process in Ukraine. However, European participants were careful to insist that Beijing’s participation in this process would need to be agreed later in settlement talks, on clearly defined and mutually agreed terms, and in a fashion that may need to align with E.U. norms (including regarding the digital aspects of reconstruction). European interlocutors also communicated that it was unlikely that Chinese peacekeepers would be seen as neutral, even if their presence provided a strong incentive for Russia not to invade Ukraine again. Among other things, European participants cited Beijing’s efforts to persuade countries not to participate in the 2024 Bürgenstock “peace conference” aimed at advancing aspects of President Volodymyr Zelenskyy’s 10-point peace plan.

As such, the view from Beijing is that European expectations are misplaced. It is in the realm of reconstruction, rather than coaxing Russia to the table, where China can realistically play the most meaningful role, but Europe continues to push for the latter while remaining wary (or at least seeking to impose constraints) on the former. Chinese participants insisted that, when it comes to Ukraine, Europe should not assume that it will be able to secure from China what it already cannot secure from Russia and the United States. Chinese participants expressed a wish for greater clarity from Europe about the role it wants China to play when it comes to ceasefire negotiations and post-conflict security arrangements.

Conclusion

The outlook for E.U.–China relations has appeared bleak for some time — and this general tenor was reflected during the dialogue session. Yet it was also clear to all that we now live in a changed world, and not only as a consequence of the war in Ukraine. This will bring many challenges but also opportunities. That said, trust is easily lost and not easily rebuilt.

In a world where mounting insecurity and mutual recriminations have become the norm, it remains unclear whether limited, targeted measures will prove sufficient to arrest the more general decline of E.U.–China ties. China continues to view its relationship with Russia as an important asset given the general descent of Beijing’s relationship with Washington into security competition, while Europe remains wary of alienating the Trump administration, given the threat it perceives as emanating from Russia. Despite shifting international economic and geopolitical pressures, Europe and China may not yet be prepared to undertake the profound shifts in strategic culture necessary to view a reset as more of an opportunity than a risk.