More Money, Less Security: Pentagon Spending and Strategy in the Biden Administration

Executive Summary

The Biden administration has requested $886 billion for national defense for Fiscal Year 2024, a sum far higher in real terms than the peaks of the Korean or Vietnam wars or the height of the Cold War. That figure could go even higher under the terms of the debt ceiling deal reached by President Biden and House Speaker Kevin McCarthy.

These enormous sums are being marshaled in support of a flawed National Defense Strategy that attempts to go everywhere and do everything, from winning a war with Russia or China, to intervening in Iran or North Korea, to continuing to fight a global war on terror that involves military activities in at least 85 countries. Sticking to the current strategy is not only economically wasteful, but will also make America and the world less safe. It leads to unnecessary conflicts that drain lives and treasure and too often contribute to instability in the regions where those conflicts are waged, as occurred with the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. In addition, elevating open–ended military commitments over other security challenges, from climate change to pandemics, risks intensifying the human and security consequences of those threats by reducing the resources available to address them.

Sticking to the current defense spending strategy is not only economically wasteful, but will also make America and the world less safe.

America’s strategic overreach is compounded by the undue influence exerted by the arms industry and its allies in Congress, backed up by over $83 million in campaign contributions in the past two election cycles and the employment of 820 lobbyists, far more than one for every member of Congress. The industry also leverages the jobs its programs create to bring lawmakers on board to fund ever higher budgets, despite the fact that the economic role of the arms sector has declined dramatically over the past three decades, from 3.2 million direct jobs to just one million now — six–tenths of one percent of a national labor force of over 160 million people. Last year alone Congress added $45 billion to the Pentagon budget beyond what the department requested, much of it for systems built in the states or districts of key members, a process that puts special interests above the national interest.

The United States could mount a robust defense for far less money if it pursued a more restrained strategy that takes a more realistic view of the military challenges posed by Russia and China, relies more heavily on allies to provide for the defense of their own regions, shifts to a deterrence–only nuclear strategy, and emphasizes diplomacy over force or threats of force to curb nuclear proliferation. This approach could save at least $1.3 trillion over the next decade, funds that could be invested in other areas of urgent national need. But making a shift of this magnitude will require political and budgetary reforms to reduce the immense power of the arms lobby.

A restrained approach could save at least $1.3 trillion over the next decade, funds that could be invested in other areas of urgent national need.

In addition to shifting to a more restrained defense strategy, a number of steps can be taken to weaken the economic grip of the arms industry on Pentagon spending and policy, including the following:

• Flag officers and senior Pentagon officials should be barred from going to work for any contractor that receives more than $1 billion per year in Pentagon contracts.

• End the practice of the defense sector funding the campaigns of members of the armed services committees and defense appropriations subcommittees of each house of Congress. Ideally, there should be a legal ban on such contributions, but if such a measure doesn’t pass legal muster the practice should be stigmatized to the point that relevant members voluntarily forgo such donations.

• Develop regional economic strategies that create civilian alternatives for heavily defense dependent areas. Given the urgent threat posed by climate change, much of this activity can be centered on creating new hubs for the development and production of green technologies.

Introduction: More Spending Doesn’t Mean More Security

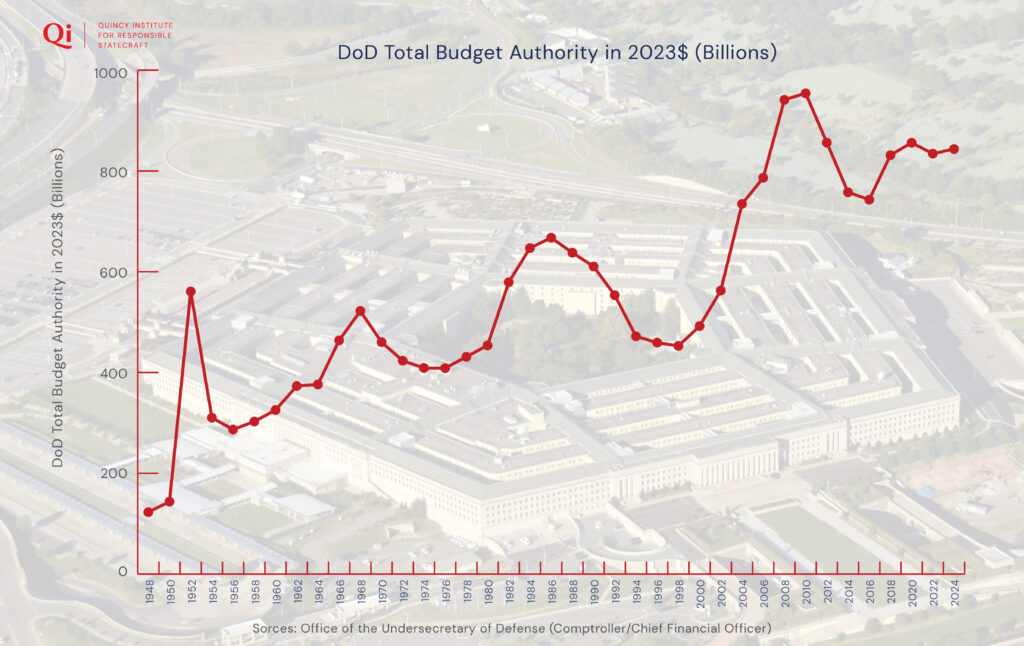

Spending on the Pentagon and related work on nuclear weapons at the Department of Energy is surging towards unprecedented levels. The Fiscal Year 2024 budget request of $886 billion for national defense is one of the highest figures since World War II, far more in inflation–adjusted dollars than the height of the Korean or Vietnam Wars or the peak year of the Cold War.1 (See figure one, below).

Figure 1: Military Spending 1948 to 2024 (In billions of dollars, adjusted for inflation)2

The $886 billion figure does not include likely emergency military aid to Ukraine. And under the terms of the legislation that lifts the debt ceiling, Congress is free to add funds for the Pentagon’s regular budget beyond the $886 billion figure. According to the Congressional Budget Office’s analysis of the debt ceiling bill, “funding designated as an emergency requirement or for overseas contingency operations would not be constrained.”3 This means, for example, that Congress could pass an emergency military aid package for Ukraine that includes not only funds needed for that nation to defend itself, but tens of billions of dollars for Pentagon or Congressional pet projects that have nothing to do with defending Ukraine. This is precisely what happened during the 10–year period covered by the 2011 Budget Control Act (BCA). The Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO) account — nominally meant to fund the Iraq and Afghan wars — was used to pay for hundreds of billions of dollars worth of items unrelated to the wars, as a way to evade the caps on the Pentagon’s regular budget contained in the BCA.4

Advocates of ever–higher Pentagon budgets often attempt to dismiss the large absolute increases in military spending in favor of measuring Pentagon spending in comparison to Gross Domestic Product (GDP). This approach is misleading for a number of reasons. Most saliently, there is no necessary correlation between military spending and the size of the economy. They grow at different rates, for different reasons. Military spending should be geared to the security threats faced by the United States, not an arbitrary comparison with GDP figures.

Military spending should be geared to the security threats faced by the United States, not an arbitrary comparison with GDP figures.

The massive Pentagon budget is supposed to be crafted to support the Biden administration’s National Defense Strategy (NDS), which was released late last year.5 But corporate influence, parochial politics in Congress, and bureaucratic inertia at the Pentagon have resulted in a budget that does not even align with the Biden defense strategy, much less a more realistic, restrained approach. Special interest politics has spurred investments in vulnerable, dysfunctional, or unnecessary systems ranging from more aircraft carriers, to the F–35 combat aircraft, to nuclear weapons in numbers far in excess of what is needed for deterrence. And as will be discussed below, the Biden strategy itself is misguided, embracing too many missions and taking a military–first approach that underutilizes non–military tools of statecraft and under invests in addressing non–traditional risks like pandemics and climate change.

Arms contractors have multiple tools of influence that can be used to distort the budget towards funding of their favored weapons programs, even if they are not the best systems for defending the country. The weapons industry made over $83 million in campaign contributions in the last two election cycles and employed 820 lobbyists, most of whom passed through the revolving door from the Pentagon or Congress to jobs in the weapons sector.6 Contractors also routinely leverage the jobs and income their programs generate in key states and districts to persuade Congress to put their special interests above the national interest. But the industry’s claims of economic benefit from their activities ignore the fact that jobs in the defense industry have dropped dramatically in the past three decades — from 3.2 million in the 1980s to one million now — and that virtually any other public investment would create more jobs than arms spending.7

In addition to the distorting effect of special interest politics, the current national defense strategy is itself a flawed document. It is an object lesson in how not to make choices among competing priorities. The Biden strategy calls for the capability to win a war with Russia or China, prepare for war with Iran and/or North Korea, and continue a global war on terrorism that involves counter–terror activities in an estimated 85 countries.8 Activities included in the estimate of counter-terror activities are “air and drone strikes, on–the–ground combat, so–called “Section 127e” programs in which U.S. special operations forces plan and control partner force missions, military exercises in preparation for or as part of counterterrorism missions, and operations to train and assist foreign forces.”9 This is the very definition of military overreach. In the meantime, the existential threat of climate change is low on the list of priorities in the NDS. The climate crisis receives slightly more attention in the administration’s broader National Security Strategy, but it has not received anywhere near the resources or attention lavished on military approaches to security.10 For more on the role of climate change in national and global security, see the appendix to this paper.

Using the administration’s current strategy as a guide to national security spending in the years to come will waste hundreds of billions of dollars while diverting resources from our most urgent challenges, many of which are non–military. Sticking to the current national defense strategy will make America and the world less safe.

A change of course is urgently needed. It’s time to develop a more restrained strategy that takes a more realistic view of the military challenges posed by Russia and China, relies more heavily on allies to provide for the defense of their own regions, shifts to a deterrence–only nuclear strategy, and emphasizes diplomacy over force or threats of force to curb nuclear proliferation.11

An approach grounded in a strategy of restraint that relies on robust diplomacy rather than using it as a backstop to a policy of military interventionism would provide greater security at far lower cost, saving at least $1.3 trillion over the next decade relative to current plans.12 The funds saved could be invested in programs that bolster non–military forms of security or to help reduce the federal deficit — or some combination of the two. Arms racing in a world of shifting power dynamics and accelerating humanitarian and environmental crises is a recipe for ongoing conflict, to the detriment of other urgent security priorities.

Arms racing in a world of shifting power dynamics and accelerating humanitarian and environmental crises is a recipe for ongoing conflict, to the detriment of other urgent security priorities.

Alongside developing a more realistic, forward–looking strategy, a key part of crafting a sustainable and effective approach to defense must involve breaking the hold of arms contractor influence over the budget process.

The Pentagon Budget: What Are We Buying?

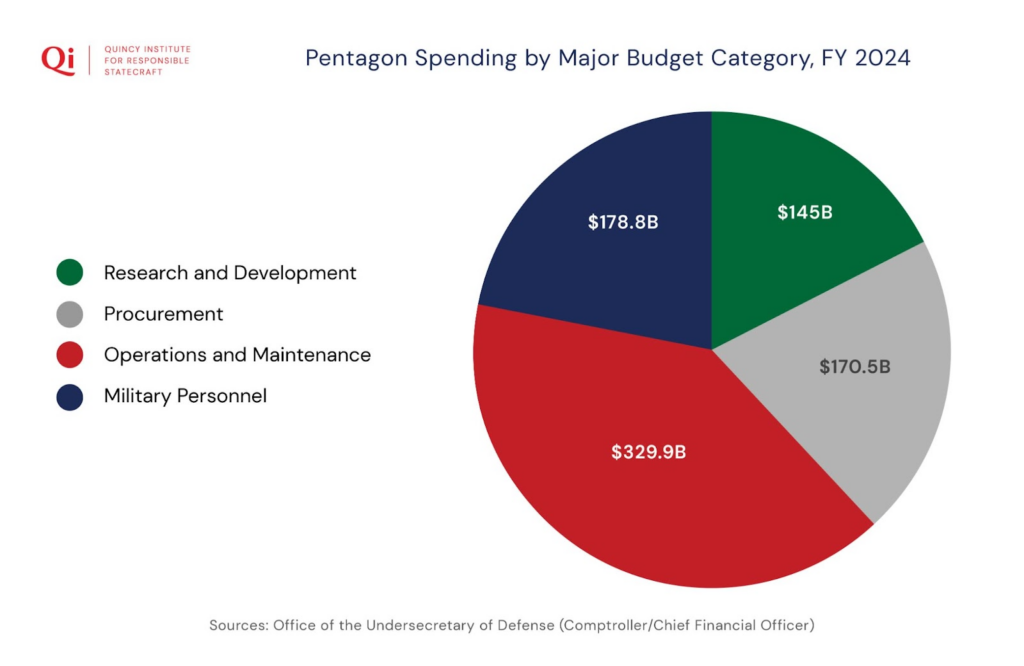

As noted above, the Pentagon budget for Fiscal Year 2024 is at one of the highest levels ever. Of the four major categories in the Pentagon budget — military personnel, operations and maintenance, procurement, and research and development — the biggest total increase came in the two accounts related to building and developing weapons, procurement and research and development (R&D). The two accounts are together slated to receive a total of $315 billion in Fiscal Year 2024. The administration has described the $145 billion set aside for R&D as the highest level ever.13 These categories of the budget are the ones that largely go to private contractors, as does a portion of the Operations and Maintenance (O&M) account. If the experience of recent years continues, more than half of the Pentagon budget will go to corporations.14 As a result, the new budget is good news for major weapons contractors like Lockheed Martin, Boeing, Raytheon, General Dynamics, and Northrop Grumman.

Figure 2: Pentagon Spending by Major Budget Category, FY 2024

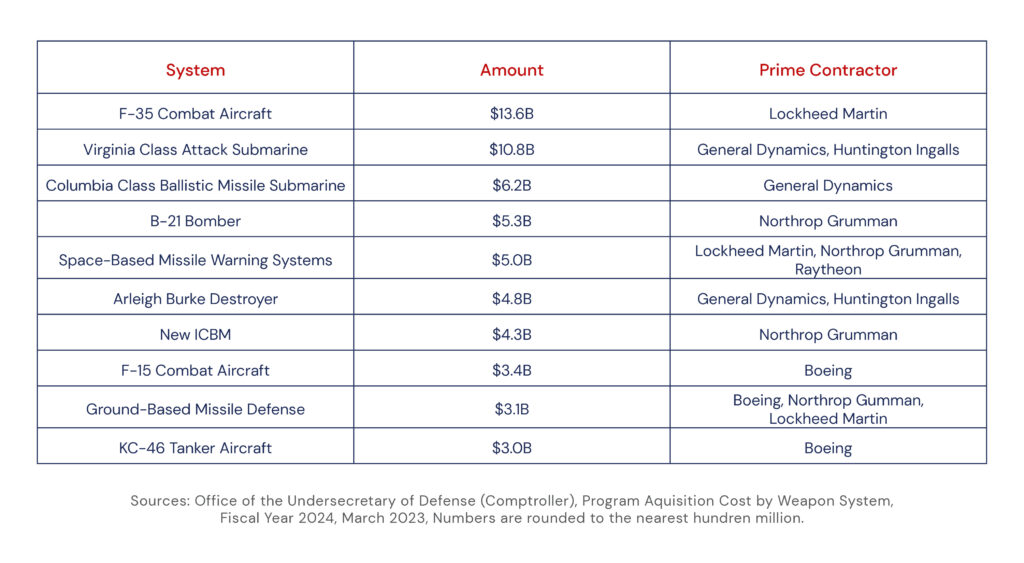

As described in more detail below, some of the biggest items on the Pentagon’s shopping list — from F-35 combat aircraft to aircraft carriers to a new intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) — are systems that are either dysfunctional or out of line with the purported goals of the department’s current strategy. For a list of the Pentagon’s top 10 weapons programs for FY 2023, ranked by amounts requested, see the table below:

Table 1: Top Ten Weapons Systems in FY 2024 Budget, by Amount Requested (in billions of dollars)

The Pentagon is also increasing spending on high tech capabilities like artificial intelligence, cybersecurity, and hypersonic weapons.15 The enthusiasm for these systems must be tempered with lessons from past surges of interest in high tech solutions, which have produced weapons and support systems that are too often expensive, hard to use, and overly complicated to maintain — and therefore of limited utility in the event of actual combat. There are also serious concerns about the potential use of next generation weaponry in an autonomous mode, launched and targeted without human intervention, as documented in a February 2023 analysis by Michael T. Klare for the Arms Control Association.16 Klare summarizes the risks as follows:

[As] countries accelerate the exploitation of new technologies for military use, many analysts have cautioned against proceeding with such haste until more is known about the inadvertent and hazardous consequences of doing so. Analysts worry, for example, that AI—enabled systems may fail in unpredictable ways, causing unintended human slaughter or uncontrolled escalation.17

The above mentioned challenges are compounded by the fact that much of the $45 billion Congress added to the Pentagon’s FY 2023 budget request was for extra ships and planes that do not clearly fit into any rational defense strategy, but are frequently included for parochial reasons — because they bring jobs and revenue to states and districts of members of Congress with the most authority over the size and shape of the Pentagon’s budget.18 In what can only be seen as a polite understatement, Pentagon Comptroller Mike McCord noted in his briefing on the Fiscal Year 2024 budget that many of the things included in the Fiscal Year 2023 Congressional add–ons were for things that were “in many cases lower priorities” from the Pentagon’s perspective.19

Does Spending Align with Strategy?

The long–awaited Biden administration National Defense Strategy (NDS), released in December 2022, is an object lesson in how not to make choices among competing security priorities.20 In addition to calling for the ability to win a war against Russia or China, the document proposes a militarized approach to nuclear non–proliferation that could involve an intervention against Iran or North Korea, plus a continued commitment to a global war on terror. It is an ambitious and ill–considered blueprint that contradicts the administration’s pledge to put diplomacy first in the conduct of U.S. foreign policy.21

But there is an additional problem with how the United States is deploying its resources for defense. As the final Fiscal Year 2023 budget and the Fiscal Year 2024 budget request demonstrate, current spending patterns do not even align with the reigning strategy, as misguided as it may be. For example, a 452,000 person Army is of little relevance to a conflict with China, which is unlikely to entail a protracted land war involving U.S. troops.22 Even in the most egregious case of Russian aggression since World War II — Ukraine — the Army has not been called on to play a direct combat role. And buying new aircraft carriers at $13 billion each makes little sense when they are vulnerable to relatively inexpensive long range strike missiles.23

The F–35 combat aircraft, which is plagued with cost and performance problems, is not well suited to most of the missions it might be called upon to carry out, from supporting troops on the ground to dropping bombs to engaging in combat with rival fighter jets. It is also riddled with defects. An analysis by the Project on Government Oversight notes that the Pentagon’s independent testing office has identified over 800 unresolved deficiencies in the F–35, at least six of which are liable to put troops at risk of injury or death.24 In addition, it’s not clear that it makes sense to buy over 2,400 of them at a lifetime cost of at least $1.7 trillion, as currently planned, when a mix of unpiloted vehicles with fewer piloted aircraft may be the wave of the future in air warfare.25

The Pentagon’s plan to spend nearly $2 trillion on a new generation of nuclear weapons over the next three decades is likely to accelerate a multi–sided arms race while sustaining a force that is far larger than is needed to deter another nation from launching a nuclear attack on the United States.26 Of particular concern is the plan to build a new intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM), which former Secretary of Defense William Perry has described as “one of the most dangerous weapons we have” because a president would have only a matter of minutes to decide whether to launch them in a crisis, increasing the risk of an accidental nuclear war sparked by a false alarm.27

The organization Global Zero has crafted an alternative, deterrence-–only nuclear posture that would abandon dangerous nuclear warfighting strategies, eliminate ICBMs, and sharply reduce the overall size of the U.S. nuclear force.28 Changes of this sort could provide a robust nuclear deterrent while setting the stage for further reductions as circumstances allow. They could also save hundreds of billions of dollars in the decades to come.

For the moment at least, the United States is also committed to maintaining an unsustainable global military footprint that includes over 750 overseas military bases and 170,000 troops stationed abroad.29 This posture makes it more likely that U.S. forces will get involved in regional conflicts that do not serve long–term U.S. interests, and it distracts attention and resources from more urgent security priorities that are not military in nature, such as pandemics and climate change. It is a posture more appropriate to a policy of persistent military intervention than a carefully considered strategy of defense and deterrence.

Obstacles to Reform: Contractor Capture of Congress

As noted above, Congress added $45 billion to the Pentagon’s budget request for FY 2023, one of the highest levels on record.30 Add–ons included five extra F–35s and a $4.7 billion boost in the shipbuilding budget.31 Other Congressional additions included 10 HH–60W helicopters, four EC–37 aircraft, and 16 additional C–130J aircraft (at a cost of $1.7 billion).32 But Congress did more than just buy weapons the Pentagon didn’t ask for. There were also provisions that prevented the Pentagon from retiring a wide array of older aircraft and ships — including B–1 bombers, F–22 and F–15 combat aircraft, aerial refueling planes, C–130 and C–40 transport aircraft, E–3 electronic warfare planes, HH–60W helicopters, and Littoral Combat Ships — thereby increasing operating costs well beyond what they otherwise would have been.33 In some cases the fingerprints of members pushing specific increases were clear, while in others there are suggestions of who may have inserted unrequested items based on their histories of promoting specific systems.

For example, Rep. Jared Golden (D–ME), who led the charge to add tens of billions of dollars to the Pentagon request when it was being considered by the House Armed Services Committee, bragged about adding a $2 billion destroyer built in his home state.34 Increases in F–35 purchases are routinely supported by the Joint Strike Fighter Caucus in the House, made up largely of members with components of the aircraft being built in their districts.35 Former Rep. Elaine Luria (D–VA) pressed for the multi–billion increase in shipbuilding funds in the FY 2023 budget, referenced above. Her district was near Huntington Ingalls Newport News Shipbuilding facility, which builds aircraft carriers and attack submarines. The shipbuilding increase was also promoted by Rep. Rob Wittman (R-VA) who, like Luria, has a district near Newport News Shipbuilding, and Rep. Joe Courtney (D-CT) whose state hosts the General Dynamics Electric Boat submarine plant, which works both on the new ballistic missile–firing submarines and attack subs. Wittman and Courtney are co–chairs of the Congressional Shipbuilding Caucus.36

The lobbying effort to prevent the Navy from retiring nine Littoral Combat Ships (LCS’s) — ships that are plagued with technical problems and irrelevant to deterring or engaging in conflict with China — is a case study of all that is wrong with the Pentagon budget process as it works its way through the Congress.37 The LCS was originally conceived as a multi–mission ship that could detect submarines, destroy anti–ship mines, and do battle with small craft of the kind used by Iran, but it proved to be poor at all of them. The ships also experienced repeated engine problems that made it hard to deploy them for any reasonable length of time. Add to this the assessment that the LCS would not be useful or capable in a potential clash with China, and the Navy decided to retire nine of the ships, even though the youngest of them had only been in service since 2020. The potential useful lifetime of an LCS was supposed to be 25 years.38

The lobbying effort to prevent the Navy from retiring nine Littoral Combat Ships (LCS’s) is a case study of all that is wrong with the Pentagon budget process as it works its way through the Congress.

Contractors and public officials with a stake in the LCS quickly mobilized to block the Navy from retiring the ships, ultimately saving five of the nine slated for retirement. Major players include a trade association representing companies that had received contracts worth $3 billion to repair and maintain the LCS at a shipyard in Jacksonville, Florida as well as other sites in the United States and overseas.39

The key Congressional players in saving the ship were Rep. John Rutherford (R–FL) and Rep. Rob Wittman (R–VA), whose Virginia district includes a major naval facility at Hampton Roads where maintenance and repair work on the LCS is done. Wittman had received hundreds of thousands in defense industry campaign contributions in 2022, including substantial donations from companies with a role in the LCS program, including Lockheed Martin, Raytheon, and General Dynamics.40 When asked if the lobbying campaign for the LCS influenced his decision to work to keep them in the fleet, he said “I can’t tell you it was the predominant factor … but I can tell you it was a factor.”41

Former Rep. Jackie Speier (D–CA), who fought to retire the LCS’s, had a harsh view of the campaign to save them:

If the LCS was a car sold in America today, they would be deemed lemons, and the automakers would be sued into oblivion . . . The only winners have been the contractors on which the Navy relies for sustaining these ships.42

As in the case of the LCS, major arms contractors routinely grease the wheels for access and influence in Congress with campaign contributions, to the tune of over $83 million in the past two election cycles.43 The donations are concentrated on members who have the most power to help them garner funding for their weapons programs. The arms industry has already expanded its collaboration with the Republicans who now head the House Armed Services Committee and the House Appropriations Committee’s defense subcommittee. New House Armed Services Committee chief Mike Rogers (R-AL) received over $511,000 from weapons-making companies in the most recent election cycle, while Ken Calvert (R-CA), the new head of the defense appropriations subcommittee, followed close behind at $445,000.44 Rogers’ home state includes Huntsville, known as “Rocket City” because of its dense concentration of missile producers, and he’ll undoubtedly try to steer additional funds to firms like Boeing and Lockheed Martin that have major facilities there.45

As for Calvert, his Riverside California district is just an hour from Los Angeles, which received more than $10 billion in Pentagon contracts in fiscal year 2021, the latest year for which full statistics are available.46

That’s not to say that key Democrats have been left out in the cold. Former House Armed Services Committee chair Adam Smith (D–WA) received more than $293,000 from the industry over the same period.47 But it’s important to note that while campaign spending may ease access to key members, it doesn’t always influence them to vote the way they want or advocate for policies of maximum benefit to industry. For example, Smith has expressed skepticism of the need for a new ICBM, voted against increasing the budget beyond what the Pentagon requested, and suggested a less aggressive and costly approach to China focused on deterrence rather than the fool’s errand of preparing to “win” a war against a nuclear–armed power.

Smiths’ views on China are especially notable in contrast with the current surge of hawkishness towards Beijing on Capitol Hill:

I think building our defense policy around the idea that we have to be able to beat China in an all-out war is wrong… If we get into an all-out war with China, we’re all screwed anyway. So we better focus on the steps that are necessary to prevent that.48

Smith reiterated this point in a January 2023 statement in which he said that “The United States can have a relationship with China that enables a more peaceful and prosperous world and a strong and thriving American economy.”49

Major arms contractors routinely grease the wheels for access and influence in Congress with campaign contributions, to the tune of over $83 million in the past two election cycles.

On the other hand, new House Armed Services Committee chair Mike Rogers has been one of the most assertive members of Congress in pushing for higher Pentagon spending. He is a longstanding booster of the Department of Defense and has ample incentives to advocate for its agenda — and more — given his own beliefs and the presence of major defense contractors in his state. There are many other members of Congress influenced to one degree or another by the flow of defense revenues to their states or districts, which is not surprising given the billions in contracts that flow to them (see table on top ten states in Pentagon contracting revenue, below).

Table 2: Top Ten States By Value of Pentagon Contract Awards, With Top Contractor Per State, FY 2021 In Billions of Dollars

The jobs card

Contractors and members of Congress with arms plants or military bases in their jurisdictions routinely use the jobs argument to argue for the funding of relevant facilities and weapons systems when arguments based on strategic need or system performance don’t carry the day. But the economic impact of Pentagon spending is greatly exaggerated, and alternative, more efficient sources of job creation can be developed.

The economic power of the arms sector rests on strategic placement of jobs and facilities in key states and districts. There are key hubs of military production, but they do not represent a majority of states or Congressional districts. Areas like Southern California (aerospace), New Mexico (nuclear weapons), Missouri (combat aircraft), Texas (combat aircraft and military bases), Virginia (shipbuilding and defense consulting), Alabama (missiles and missile defense), and Connecticut (aircraft engines, helicopters, and submarines) receive substantial amounts of military spending, and their representatives are well represented on the key committees — armed services and defense appropriations — that determine the size and shape of the Pentagon budget.50 Representatives from states with a high concentration of military spending have a disproportionate impact in determining how much the Pentagon spends overall, as well as on key weapons systems.

At the national level, direct employment in the weapons sector has dropped dramatically in the past four decades, from 3.2 million in the mid–1980s to one million today, according to figures compiled by the National Defense Industrial Association (NDIA), the arms industry’s largest trade group.51 While significant, it is important to note that the one million jobs in the defense sector represent just six–tenths of 1 percent of the U.S. civilian labor force of over 160 million people.52 In short, weapons spending is a niche sector in the larger economy, not an essential driver of overall economic activity.

Representatives from states with a high concentration of military spending have a disproportionate impact in determining how much the Pentagon spends overall, as well as on key weapons systems.

Arms related employment will rise in the context of rising Pentagon budgets and ongoing expenditures on arming Ukraine, but total employment in the defense sector will still be modest relative to job levels during the Cold War. The historic reduction in defense-related jobs has occurred despite the fact that the current military budget is far higher than spending in the peak year of the Cold War.

Why have defense jobs fallen so far while spending has risen so much? There are a number of factors, including outsourcing to other countries of components and, in some cases, final assembly of major weapons systems; automation, from computer-assisted machine tools to 3D printing of parts; production of fewer units of more expensive systems; and a related concentration of employment on engineers and other technical personnel rather than factory workers.53 Wages in the arms industry may be diminishing as well, as there has been a trend towards moving arms factories to right–to–work, anti–union states, as when Lockheed Martin moved its F–16 assembly line from Texas to South Carolina.54

The historic reduction in defense-related jobs has occurred despite the fact that the current military budget is far higher than spending in the peak year of the Cold War.

The reductions in defense–related employment are masked by the tendency of major contractors like Lockheed Martin to exaggerate the number of jobs associated with major programs. For example, Lockheed Martin claims that the F–35 program creates 298,000 jobs in 48 states.55 But a close look at their estimate suggests that they are using inflated “multipliers” — a technique that attempts to capture the ripple effect of direct production to encompass employment created at weapons subcontractors and at establishments that benefit from the expenditure of wages by front–line defense workers, like restaurants and retail facilities. Using a multiplier is a legitimate method for attempting to measure the full economic impact of a given expenditure, but in the case of the F–35, Lockheed Martin dramatically overestimated the indirect effects of spending on the aircraft. An accurate estimate of jobs tied to Pentagon spending on the F–35 would be less than one–third the number claimed by Lockheed Martin — in the range of 75,900 to 82,800, based on average annual expenditures on the program of $11 to $12 billion in recent years, and estimates by the Brown University Costs of War Project that military spending creates about 6,900 jobs per billion dollars spent.56 There are additional jobs tied to exports of the aircraft, but many of those jobs are located overseas, at places like the final assembly plants for the F–35 in Italy and Japan, as well as large numbers of major subcontractors located in Europe and East Asia. Even if there were a net gain of tens of thousands of jobs from F–35 exports, the full number of jobs tied to the plane would be far below the figures put forward by Lockheed Martin.57

An accurate estimate of jobs tied to spending on the F–35 would be less than one–third the number claimed by Lockheed Martin.

As for the geographic spread of the impact of the F–35, most of the economic benefits go to a relatively small number of states and localities. According to Lockheed Martin’s own estimate, just three states — Texas, California, and Connecticut — account for nearly half of the jobs the company claims are being created by the program.58

But even given the fact that the job impact of Pentagon spending is much more limited than advertised, the jobs that do exist generate considerable political clout because, as noted above, they are in the states and districts of members of Congress with the most sway over how much is spent on weapons production and research and development each year. Addressing this problem will require a focused investment strategy to ease the transition of defense-dependent communities and workers to other sources of jobs and income.59

The revolving door

Beyond campaign contributions and the jobs card, one of the industry’s strongest tools of influence is the infamous revolving door between government and the weapons sector. A 2021 report by the Government Accountability Office found that, between 2014 and 2019, more than 1,700 Pentagon officials left the government to work for the arms industry.60 And that was a conservative estimate, since it only covered personnel going to the top 14 weapons makers.61 And a recent report by the office of Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D–MA) identified “672 cases in 2022 in which the top 20 defense contractors had former government officials, military officers, Members of Congress, and senior legislative staff working for them as lobbyists, board members, or senior executives. In 91 percent of these cases, the individuals that went through the revolving door became registered lobbyists for big defense contractors.”62

Former Pentagon and military officials working for such corporations are uniquely placed to manipulate the system in favor of their new employers. They can wield both their connections with former colleagues in government and their knowledge of the procurement process to give their companies a leg up in the competition for Defense Department funding. As the Project on Government Oversight has noted in “Brass Parachutes,” a report on that process: “Without transparency and more effective protections of the public interest, the revolving door between senior Pentagon officials and officers and defense contractors may be costing American taxpayers billions.”63

Between 2014 and 2019, more than 1,700 Pentagon officials left the government to work for the arms industry.

Contractors are also well–positioned to shape future debates on Pentagon spending and strategy. For example, a newly formed congressional commission charged with evaluating the Pentagon’s National Defense Strategy is heavily populated with experts and ex–government officials with close ties to weapons makers, either as executives, consultants, board members, or staffers at think tanks with substantial industry funding.64 The last time Congress created a commission on strategy, its membership was also heavily slanted towards individuals with defense industry ties, and it recommended a 3 to 5 percent annual increase in Pentagon spending — adjusted for inflation — for years to come, well more than what the department was then projecting to spend.65 The commission’s figure became a rallying cry for Pentagon boosters like Mike Rogers and former ranking member of the Senate Armed Services Committee Sen. James Inhofe (R–OK) in their efforts to push spending on the department ever higher. Inhofe treated the document as gospel, at one point waving a copy of the report at a Congressional hearing on the Pentagon budget.66

The Pentagon and the arms industry also invest heavily in supporting think tanks. A 2020 study by the Center for International Policy found that between 2014–19, the top 50 think tanks in the United States had received over $1 billion in funding from the Pentagon or military contractors. The report summarizes the potential impact of this funding as follows:

This funding can significantly influence the work of think tanks. It can lead to a think tank producing reports favorable to a funder, think tank experts offering Congressional testimony in support of a funder’s interests, or its scholars working closely with a funder’s lobbyists.67

It’s not unusual for think tanks funded by the arms industry to advocate for projects and policies that benefit weapons contractors, from touting specific systems like the B–21 bomber or F–35 combat aircraft to pushing for a higher Pentagon topline.68 In some cases this may be a case of the contractor helping to amplify messages and analyses that have already been arrived at by the recipient institution, while in others the positions of the think tanks may be influenced directly by their corporate funders. In either case the net result is a wider dissemination of viewpoints favorable to the weapons sector. This effect is compounded by the fact that analysts funded by weapons firms are often not identified as such in the media or Congressional testimony, thereby depriving the public of the ability to take that funding into account in assessing the arguments of industry–supported individuals and organizations.69

A new strategy and new investment patterns cannot be achieved without changes in the political power of the arms industry and its allies in Congress and the Pentagon. The needed reforms will be both political and economic in nature, as outlined at the end of this report.

How Strategic Overreach Drives Overspending on the Pentagon

In addition to special interest politics, the other main driver of Pentagon spending levels is an overly ambitious global defense strategy. Current U.S. strategy is grounded in military overreach — preparing to fight on multiple fronts and exaggerating the military threats posed by real and potential adversaries. America’s misguided strategy accounts for the lion’s share of overspending on the Pentagon. For example, the $45 billion added to Pentagon spending by Congress in the Fiscal Year 2023 budget — much of it for parochial projects benefiting the states or districts of key members — accounted for just over 5 percent of the department’s allocation for that year.70 It was a waste of money certainly, but not the main driver of spending. Of course, add–ons don’t give a full picture of the impact of pork barrel politics, since special interest concerns also bolster the case for weapons systems that are part of the main budget proposal and limit the Pentagon’s ability to shed outmoded systems. But ultimately it is the size of the military that determines the main parameters of the budget. And the size of the force is largely justified by the scope of the strategy underlying it.

For example, the Congressional Budget Office has outlined three illustrative approaches that would save $1 trillion in Pentagon spending over the next decade, and the key source of savings is a reduction in the size of the active duty military by up to 19 percent.71 Troops need to be fed, housed, trained, equipped, transported, and provided with health care, so reducing the size of the force saves more money than canceling or slowing a weapons program here or there.

The U.S. military is structured as a global force, but there are some rough correlations between spending on weapons and personnel and specific challenges. First, the focus on China has been used as a rationale for expanding the Navy, investing in long–range strike systems, expanding the U.S. industrial base for the production of missiles and ammunition, and expanding research on hypersonic weapons and artificial intelligence. Vladimir Putin’s threats to use nuclear weapons have bolstered the case for the Pentagon’s three decades–long plan to build a new generation of nuclear–armed bombers, missiles and submarines, as has the growth of China’s nuclear force and continuing nuclear arms development by North Korea. These same challenges have underpinned tens of billions in spending on medium– and long–range missile defense systems. The Russian invasion of Ukraine has stoked demand for ammunition, artillery, and tactical missiles. And continued concerns about Iran have been used as a rationale to maintain a small contingent of combat troops at major U.S. military bases in the Middle East. The totality of U.S. global commitments are given as the reason to maintain a 2.1 million strong military force, with over 1.3 million on active duty and over 700,000 in an increasingly active reserve force.72 In short, substantial savings in military spending will require a significant shift in America’s national defense strategy.

A review of the U.S. approach to its current security commitments is set out below.

Great power competition

The Pentagon has defined Russia as an “acute threat” and China as a “pacing challenge” in determining the size, shape, and cost of U.S. military forces.73 We will address these rationales in turn.

Russia’s brutal full–scale invasion of Ukraine is setting the stage for a sharp uptick in U.S. military aid and spending in the years to come, absent a more realistic assessment of the risks posed by Moscow going forward. The United States has already authorized over $113 billion in aid to Ukraine since the start of the Russian invasion in February 2022, more than half of which — $62 billion — has gone to the Pentagon.74 In turn, $36.9 billion of that sum has already been committed to military aid to Ukraine and front line NATO allies in the Ukraine conflict, with billions more likely in the year to come.75

Direct military aid to Ukraine is not the only impact of the Russian invasion. Supplying Ukraine with adequate amounts of artillery, ammunition and tactical missiles has strained U.S. stocks and production capabilities, prompting widespread calls from industry, the Pentagon, and the military services for a permanent expansion of the military–industrial complex, including building new factories to provide the capability to double or triple the numbers of artillery shells, HIMARS missiles, and other key items relevant to a state–to–state ground war like that being conducted currently in Ukraine.76 These efforts to expand the defense industrial base could add tens of billions of dollars to the Pentagon budget beyond current levels over the next three to five years.77 But it is not clear that it is necessary or advisable to permanently expand the U.S. defense industrial base to deal with issues raised by supplying weapons to Ukraine. It would be difficult to reverse such a process given that it would create yet another set of vested interests in ongoing investment and production in specific capabilities that may not be relevant five or ten years down the road.78 In short, we’re investing billions in facilities that may not be needed by the time they’re operational.

This year will be a critical phase of the Ukraine war, as President Volodymyr Zelensky calls for more sophisticated weapons — from fighter planes to long-range missiles — to make further gains in rolling back Russian forces, and, in his view, drive the Russian military from every inch of Ukrainian territory, including Crimea.79 A number of analysts and Biden administration officials have suggested that this all–out strategy is unrealistic, and that the best Ukraine can hope for is a successful offensive that will put it in a stronger position to negotiate an acceptable end to the conflict. A February 2023 piece in the Washington Post suggests that the Biden administration’s current view on the conflict is as follows: “Biden’s aides say they are pursuing the best course of action: empowering Ukraine to retake as much territory as possible in coming months before sitting down with Putin at the negotiating table.”80 At this point no one can predict the outcome of the war, but regardless of where it heads this year, substantial amounts of U.S. military aid to Ukraine are likely to continue, either to fend off the Russian invasion or to provide ongoing security in a post-war environment.

Washington has also used Russia’s conduct to bolster support for the buildup of U.S. strategic weapons, on the argument that Putin is a rogue actor who has already resorted to nuclear threats in Ukraine and might go so far as to employ such weapons in a future scenario.81 Hence, in theory, the need to enhance U.S. deterrence by building a new generation of nuclear weapons. But, as the organization Global Zero has set out in its alternative nuclear posture, the United States can maintain deterrence with a considerably smaller nuclear arsenal, and it can forgo most elements of the Pentagon’s proposed three–decades long, $2 trillion plan to build a new generation of nuclear armed bombers, missiles and submarines.82 Russia is unlikely to use nuclear weapons in Ukraine, unless the Putin regime believes it is at risk of a catastrophic defeat, or a collapse of the Russian government itself. Taking care to avoid escalatory actions or rhetoric and keeping open a diplomatic track amidst the ongoing conflict are the best ways to prevent the use of a nuclear weapon in Ukraine. Overbuilding the U.S. strategic arsenal will have no influence on Vladimir Putin’s nuclear calculus with respect to Ukraine.

One aspect of the Russian invasion of Ukraine that has not received adequate attention is what it has revealed about the relative weakness of its military forces. Russia has been fought to a standstill by a nation with a much smaller population and economy, displaying serious flaws in strategy, training, and morale. Moscow continues to maintain the ability to inflict devastating damage on civilian infrastructure within Ukraine, but it is unlikely to “win” the war, except perhaps if it transforms itself into a long, grinding war of attrition, and even then the outcome would be uncertain. One lesson for the United States and NATO is that whatever the preferences of its leadership, Russia is in no position to launch a successful military attack against any member of the NATO alliance in the foreseeable future. In addition, if properly invested and coordinated, the hundreds of billions in current and prospective military spending by European NATO nations should be more than enough to craft an effective deterrent force against potential Russian aggression.83 This would allow for a reduction of U.S. forces and resources devoted to European contingencies.

Taking care to avoid escalatory actions or rhetoric and keeping open a diplomatic track amidst the ongoing conflict are the best ways to prevent the use of a nuclear weapon in Ukraine.

As for China, its greatest challenges to the United States are economic and political, not military. On the military front, the United States spends almost three times what China does on its military and has strong allies in the region of a kind that China does not, including Australia, Japan, and South Korea, even as the Biden administration is moving to build closer military ties with India.84

The principal military question is whether the United States and China go to war over Taiwan, a scenario that is more contingent on diplomatic engagement than military buildups. The surest way to prevent a war with China over Taiwan is to revive an unequivocal commitment to the One China policy. Reaffirming the One China policy, which limits U.S. military commitments and political relations with Taiwan as long as Beijing seeks only peaceful means to integrate Taiwan into China, is one essential step. In addition, engaging in talks to establish some short–term guardrails and ongoing channels of communication to lower the temperature of U.S.–China interactions should be a priority.85

The United States spends almost three times what China does on its military.

Unfortunately, President Biden has made a number of statements on coming to Taiwan’s defense militarily that do not align with existing policy, forcing the State Department to backtrack from the President’s words and make clear that the U.S. policy remains one of strategic ambiguity. But as this report went to press, there were signs that the administration might be seeking ways to reduce tensions between Washington and Beijing to avoid a new Cold War.86

Michael Swaine of the Quincy Institute has described the path back to a more stable mutual understanding of the One China policy and the resulting easing of tensions over the status of Taiwan as follows:

The only logical solution to this problem is for Washington and Beijing to explicitly agree on a set of reciprocal, credible assurance measures that will breathe life back into their original understanding regarding Taiwan. To keep the peace across the Taiwan Strait, there is no viable alternative to exchanging clear, credible assurances of U.S. limits on relations with Taiwan and its implacable opposition to any unilateral move toward Taiwan independence, with China reciprocating by reiterating assurances that it rejects any timeline for unification and will end its military exercises near the island of Taiwan.87

In short, U.S. policy towards China should be a mix of military deterrence and diplomatic reassurance. Unfortunately, at the moment the military element is being overplayed while the reassurance aspect is underdeveloped.88 The military deterrence element of the strategy should follow the approach of “active denial” that has been described in a Quincy Institute report that was the product of a task force of defense and regional experts of diverse views and backgrounds.89 Active denial involves raising the cost to China of any military intervention in the region by arming allies with appropriate defensive systems and crafting a distributed force posture in the region that is less threatening to Beijing but will still serve as a deterrent against Chinese aggression.

In the longer term and as China’s rise continues, the United States should adjust its defense perimeter to take account of the new power realities in Asia. This means focusing on its core allies — namely Japan, South Korea, and Australia — and drawing down its alliance or alliance–like commitments to other partners.90

Regional challenges: Iran and North Korea

The approach to regional challenges like the potential development of nuclear weapons by Iran and North Korea’s continued investment in its nuclear arsenal that is outlined in current strategy documents devalues diplomacy in favor of preparation for and threats of military conflict. The persistent presence of military options in U.S. strategy comes even as the Iran nuclear deal, known formally as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), is in limbo and could well collapse.91 Before the Trump administration abandoned it, the agreement was working to curb Iran’s nuclear ambitions at minimal cost to the United States and its allies. The pullout from the treaty was a strategic blunder with potentially devastating regional consequences, absent a revival of U.S. participation or a new diplomatic opening to address Iran’s nuclear program and head off the prospects of war over Tehran’s pursuit of a nuclear capability.

If the Biden administration fails to redeem its pledge to rejoin the JCPOA, as now seems likely, it will be in part due to a lack of urgency and flexibility in pursuing an agreement. In a December 2022 speech, Secretary of State Anthony Blinken implied that the United States was still committed to the deal, while at the same time making a veiled threat to use force if Tehran pursues a nuclear weapon:

We continue to believe that diplomacy is the best way to prevent Iran from obtaining a nuclear weapon. But should the Iranian regime reject that path, its leaders should make no mistake that all options are on the table to ensure that Iran does not obtain a nuclear weapon.92

Blinken’s statement was contradicted by a November 2022 statement by President Biden himself. A video of a political rally, which was only made widely available in late December, shows Biden responding to a question about the Iran deal by saying, “It’s dead, but we’re not going to announce it.”93 When asked about the video, National Security Council spokesperson John Kirby said “there is no progress happening with respect to the Iran deal now. We don’t anticipate any progress, anytime in the near future. That’s just not our focus.”94

The failure of the United States to rejoin the Iran deal is a major loss for stability and security in the Persian Gulf region. Not only was the agreement effective in preventing Iran from obtaining a nuclear weapon or advancing its capabilities for doing so, but it was a prime example of the kind of effective multilateral diplomacy that will be needed to address other global problems, from issues of the environment to war and peace. Placing the United States, the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Russia, China and representatives of the European Union on the same page with the Iranian government was a major achievement that could have paved the way for a more balanced U.S. approach to the region, in which negotiations with Iran on other issues might have been possible.

With a U.S. return to the nuclear deal now on hold, there is a renewed danger that Washington may be drawn into a war against Iran. One possible path to war would come via support for Israeli military actions against Iran, like the January 29 strike on a military compound there, which the United States not only failed to condemn, but seemed to tacitly support.95 To make matters worse, Tom Nides, the U.S. ambassador to Israel, told a gathering of the Conference of Presidents of Major American Jewish Organizations that “Israel can and should do whatever they need to deal with [Iran] and we’ve got their back.”96

The failure of the United States to rejoin the Iran deal is a major loss for stability and security in the Persian Gulf region.

A new diplomatic initiative to rein in Iran’s nuclear program is needed, not only to keep Tehran from developing deployable nuclear weapons, but also to head off a potential war in the region. While U.S. officials are not publicly pushing for a conflict at present, military force is not off the table as a potential option, as noted above. And as the new Israeli government takes an increasingly aggressive posture towards Iran, the risk of the United States being drawn into a war with Tehran will likely increase.

The time for negotiations may not be ripe at present, in the midst of a brutal crackdown on human rights and democracy advocates in Iran, but they should be resumed as soon as practically possible. And U.S. officials should bear in mind that military action against Iran will not only make it more difficult for activists to effectively oppose the regime — by strengthening hardliners in Tehran — but it will also likely kill or injure average Iranians who have no input over the policies pursued by the regime. Military action against Iran would be destabilizing, and would likely drive Tehran to further accelerate its nuclear weapons program while increasing the prospects of greater conflict throughout an already war–torn region. As Ali Vaez, an Iran expert at the International Crisis Group, has pointed out, a full–scale military intervention in Iran would “make the Afghan and Iraqi conflicts look like a walk in the park.”97

Military action against Iran would be destabilizing, and would likely drive Tehran to further accelerate its nuclear weapons program while increasing the prospects of greater conflict throughout an already war–torn region.

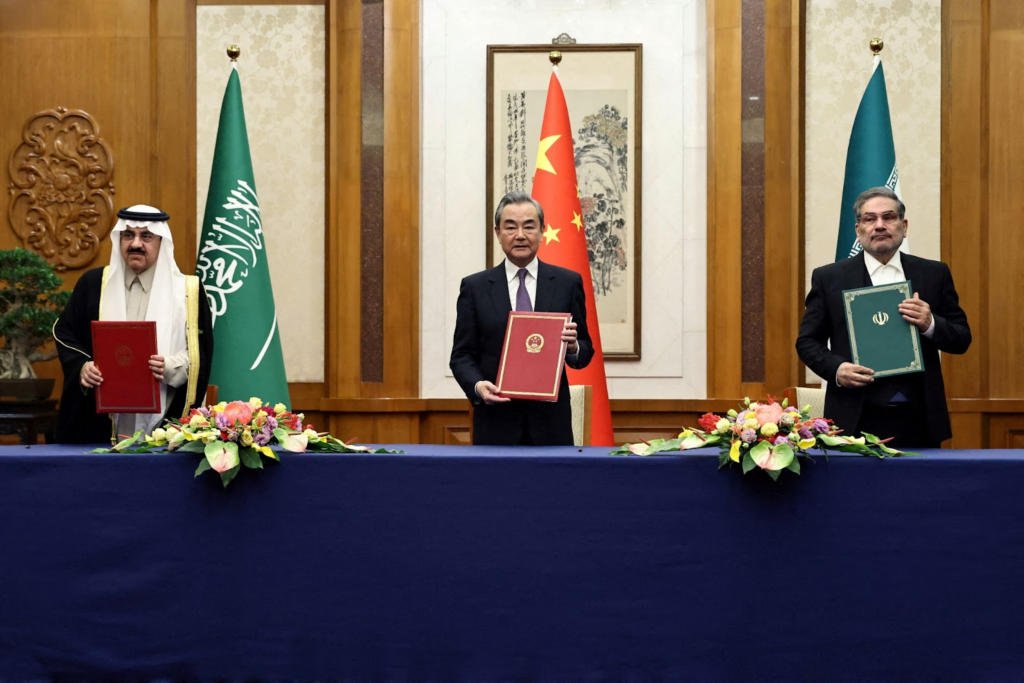

Meanwhile, the security environment in the Middle East may be transformed for the better by the opening of diplomatic relations between Saudi Arabia and Iran, rivals that have often fueled opposite sides of key conflicts in the region. The full impact of the deal, which was brokered by China, remains to be seen, but it opens up possibilities for promoting greater long–term peace and cooperation in the region.98

Diplomatic negotiations with North Korea, however challenging, are a far preferable option to war, which could not be won without catastrophic numbers of casualties in South Korea and the possibility of nuclear strikes against U.S. allies in East Asia. Should negotiations prove impractical at this moment, it’s important to note that deterrence is likely to hold in the current context, given the vast nuclear superiority of the United States over North Korea. North Korea is extremely unlikely to attack the United States with a nuclear weapon given that it would unquestionably see its own society completely destroyed in return. Such an attack would only occur via miscalculation or if North Korean leader Kim Jong Un perceived an imminent attack that put himself and his regime at risk of annihilation. Hence the need for communication, and the imperative to refrain from saber–rattling.

Former Secretary of Defense William Perry has underscored these points, noting that North Korea’s nuclear capacity “does not mean they are intending to initiate a nuclear war.” Perry has gone on to say that there are real risks, but that they are not posed by the danger of an intentional attack on the United States by North Korea: “North Korea is bombastic and warmongering in its rhetoric, and often ruthless in its tactics. But the regime is not irrational. Its leaders seek survival, not martyrdom. But as long as they possess these weapons in a region infused with intense and long–standing conflicts, the risk of blundering into a nuclear catastrophe through miscalculation or brinkmanship gone awry is unacceptably high.”99

Following the regional strategy outlined above would allow for a substantial reduction in the large forward military presence that the United States currently maintains in each of these potential zones of conflict, reducing the overall size of the U.S. military in the process.

Fears that other great powers will expand their military presence in the Middle East if the United States pulls back are overblown. Russia’s presence in Syria is based on a longstanding interest, and it is not likely to be replicated elsewhere in the region. In addition, Moscow’s brutal full–scale invasion of Ukraine has drained its resources, leaving it in a weakened state.100 Russia is attempting to strengthen ties with Egypt via arms sales and military–to–military relationships and its proxy, the Wagner Group, has taken sides in a number of conflicts in North Africa, but neither of these inroads in the region are most effectively countered by a large U.S. troop presence.101

Fears that other great powers will expand their military presence in the Middle East if the United States pulls back are overblown.

China is a top trading partner of major Middle Eastern powers, including rivals Iran and Saudi Arabia, but there is no indication that it seeks to replicate the large U.S. military presence in the area should Washington reduce the level of U.S. personnel there.102 China’s role in helping broker the recent normalization of relations between long–time regional rivals Iran and Saudi Arabia is an example of how it has used its political and economic ties to key players to influence the political developments in the region.103

A less militarized global counter–terror strategy

The 20 year–plus global counter–terror campaign waged by the United States since September 11, 2001 has cost enormously in lives and resources, with mixed results in terms of actually curbing terrorism. On the U.S. domestic front, there has not been another attack on the scale of the 9/11 attacks, but that can be attributed more to improvements in homeland security than to overseas operations.104

The wars in Iraq and Afghanistan — one that was explicitly justified as a battle against al Qaeda and the Taliban and the other that morphed into a fight against the Iraqi opposition and, eventually, ISIS — have cost over $8 trillion, resulting in the loss of over 387,000 civilian lives.105

President Biden deserves credit for ending America’s 20–year war in Afghanistan, but in his speech announcing the end of the U.S. military presence in that nation he made it clear the larger U.S. campaign against terrorism was not over, and might even be intensified:

The terror threat has metastasized across the world, well beyond Afghanistan. We face threats from al-Shabaab in Somalia; al Qaeda affiliates in Syria and the Arabian Peninsula; and ISIS attempting to create a caliphate in Syria and Iraq, and establishing affiliates across Africa and Asia… the threat from terrorism continues in its pernicious and evil nature. But it’s changed, expanded to other countries. Our strategy has to change too.106

To the extent that there has been a shift in strategy, it has been to rule out large, boots–on–the-ground operations like the war in Afghanistan and rely instead on the longstanding policy of drone strikes, arming and training local forces, and deploying Special Forces that has been undertaken in dozens of countries for years. There is no indication that the Biden administration has substantially pulled back from this wide–ranging approach.107

Many of the human consequences of the wars can be attributed to terror groups like al Qaeda or ISIS, opposition groups like the Taliban, or repressive governments like the Assad regime in Syria. But direct and indirect U.S. military interventions have more often increased than reduced the human costs of these wars, and in cases where they have temporarily tamped down terrorist activities they have come at a high cost in blood and treasure, including thousands of deaths among U.S. service members alongside hundreds of thousands of physical and psychological wounds, from lost limbs to traumatic brain injuries to post–traumatic stress syndrome.108

U.S. counter–terror operations in Africa have fared no better, with a proliferation of terrorist groups occurring alongside U.S. drone strikes, Special Forces deployments, and arms and training of local government forces designed to counter those organizations. Stephanie Savell of the Costs of War Project at Brown University has summarized some of the main problems with the current approach:

Many governments use the U.S. narrative of terrorism and counter-terrorism . . . to repress minority groups, justify authoritarianism, and facilitate illicit profiteering, all while failing to address poverty and other structural problems that lead to widespread frustration with the state. Thus, in a vicious cycle, what the U.S. calls security assistance actually accomplishes the opposite . . . it has fed insecurity, bolstering the militants that react against government injustices exacerbated by this aid.109

Given the results of current policy, a new, less militarized approach to countering global terrorism is urgently needed.110

Conclusion and Recommendations: Outlines of a New Strategy

As noted above, current Pentagon spending patterns do not align with the department’s own strategy, largely due to parochial interests that distort military investment patterns. But the current strategy itself needs to be subjected to scrutiny if the United States is to achieve the best defense at the lowest cost.

The latest National Defense Strategy (NDS), released in December 2022, is an exercise in strategic overreach that endorses a costly and unsustainable global footprint that includes over 750 overseas military bases and 170,000 troops abroad.111 The strategy calls for building the capability to win a war against Russia or China; engage in regional conflicts with Iran or North Korea; and continue America’s decades long global war on terrorism. The strategy gives lip service to addressing non–military risks like climate change, but resources allocated for these challenges lag far behind the amounts invested in the Pentagon and related military activities. For example, the $37 billion per year set aside for addressing climate change in the 2023 Inflation Reduction Act is less than five percent of the $858 billion devoted to military spending in that year.112 For more on the Pentagon’s potential role in a larger strategy for addressing climate change see the appendix.

A more restrained strategy would provide better defense per dollar spent while reducing the risk of being drawn into devastating and unnecessary wars. The outlines of such an approach should include taking a more realistic view of the military challenges posed by Russia and China; relying on allies to do more in defense of their own regions; forgoing the capability to intervene in Iraq– or Afghanistan–style counter–terror or nation building exercises that involve large numbers of boots on the ground; paring back the U.S. overseas military presence, starting with a reduction in basing and troop levels in the Middle East; and scaling back the Pentagon’s plan to spend up to $2 trillion on a new generation of nuclear weapons over the next three decades in favor of a deterrence only strategy that would entail fewer weapons and an abandonment of costly and dangerous nuclear warfighting strategies.113 On the non–military side of the ledger, it is crucial that U.S. strategy encompass a serious commitment to addressing the potentially existential threat of climate change.

A more thoroughgoing approach that definitively shifted away from the current “cover the globe” strategy could save hundreds of billions more over the next decade.

Such an approach could save well over $100 billion per year, as evidenced by an illustrative report released by the Congressional Budget Office in late 2021. The report sketches out three scenarios, all involving a less interventionist, more defensive approach that includes greater reliance on allies. Each option would reduce America’s 1.3 million strong active military force — by up to one–fifth in one scenario. Total savings from the CBO’s proposed changes would be $1 trillion over a decade’s time.114

A more thoroughgoing approach that definitively shifted away from the current “cover the globe” strategy that entails being able to fight virtually anywhere in the world, without allies if necessary, could save hundreds of billions more over the next decade. There are also savings to be had by cutting bureaucracy and making other changes in defense policy in addition to scaling back America’s global military reach. To cite just two examples, cutting back on the Pentagon’s cohort of over half a million private contract employees and scaling back the Pentagon’s nuclear weapons modernization program would together save well over $300 billion over a decade, resulting in potential savings of $1.3 trillion or more from a new strategy.115

A status quo policy will lead to diminishing security at an unsustainable cost.

A new security strategy coupled with a new economic approach that weakens the power of the military–industrial complex can result in a more effective defense that is better able to meet the most urgent challenges of our era. The United States can have a better defense posture for hundreds of billions of dollars less than the current approach, which is characterized by strategic overreach and dysfunctional budgeting and investment processes. Moving in this direction will require significant political and economic reforms to push back against the parochial, pork barrel politics that have hamstrung past efforts to shift U.S. strategy and spending. Change will be difficult, but it is essential if the United States is to have a robust defense in the years and decades to come. A status quo policy will lead to diminishing security at an unsustainable cost.

In addition to shifting to a more restrained strategy as outlined above, there are a number of measures that could be taken to weaken the grip of the arms industry on defense policy, which would help reduce overspending on the Pentagon and make it possible to align spending with strategy rather than special interests.

Policy reforms that could help reduce the power of the arms lobby include campaign finance reform, curbs on the revolving door, and measures to reduce price gouging and cost overruns that fill the coffers of weapons firms without providing value added in terms of security. A few examples of such reforms are set out below.

Curbs on the revolving door

When it comes to the revolving door, time is the enemy of influence. A substantial cooling off period moving from the Pentagon or Congress to the arms industry would mean that key contacts with former colleagues would be less useful as personnel in the Executive Branch turn over. And potential “revolvers” might be more likely to find employment outside of the defense sector in the meantime. And more systematic reporting on revolving door hires — and penalties for government employees moving into industry who do not report those moves — should also be implemented.116

Ideally, flag officers and senior Pentagon officials should be barred from going to work for any contractor that receives more than $1 billion per year in Pentagon contracts.

The most comprehensive current proposal to address the revolving door issue is Sen. Elizabeth Warren’s Department of Defense Ethics and Anti-corruption Act. The bill would impose a four–year ban on arms contractors from hiring DoD officials and prevent them from employing former DoD employees who managed their contracts. The Act would also require defense contractors to provide detailed information to the Pentagon on former senior DoD officials who they have hired, among other provisions.117

Creating alternative economic opportunities

Weakening the grip of pork barrel politics over defense spending decisions will require regional economic strategies that create civilian alternatives for heavily defense dependent areas like those mentioned above.

Given the urgent threat posed by climate change, much of this activity should be centered on creating new hubs for the development and production of green technologies.

According to research by Heidi Peltier of the Costs of War Project at Brown University, investments in green energy create 40 percent more jobs than spending on the military. Spending on infrastructure would also create 40 percent more jobs per amount spent than military outlays, while investments in health care and education would each create over two times as many jobs.118 If the Pentagon budget were cut by $120 billion and the funds shifted to green manufacturing, there would be a net increase of 250,000 jobs nationwide.119 The question is whether such a shift is feasible in the short–term, and whether the jobs created would be in areas where arms industry workers were being displaced by reductions in the Pentagon budget. But the potential exists for a transformation of the national and local economies from dependence on Pentagon spending to more forward looking industries that address the security challenges of the future.120

Campaign finance reform

Supreme Court decisions like Buckley v. Valeo have placed limits on what can be done to curb campaign spending at the federal level, but there are a number of initiatives that could reduce the relative clout and access of arms companies. Providing federal matching funds for small donations to Congressional races would be one such measure. If candidates can mount successful campaigns using a combination of small donors and government matching funds they are less likely to need the support of large corporations in the defense sector or elsewhere.121

Ultimately, the goal of policy should be to end the practice of major weapons contractors funding the campaigns of members of the armed services committees and defense appropriations subcommittees of each house of Congress through Political Action Committees and direct donations provided by company employees.122 Ideally, there should be a legal ban on these contributions, but if such a measure doesn’t survive a legal challenge the practice should be stigmatized through pressure from constituents and in the media to the point that relevant members voluntarily forgo such donations.

Appendix: Pentagon Spending and the Challenge of Climate Change

The Pentagon has acknowledged the potential security challenges posed by the climate crisis, but is taking a fairly narrow, institutional approach to a larger global problem – protecting naval bases, reducing fuel use on the battlefield, and preparing for conflicts that may be sparked by the surge of climate refugees.

As the world’s largest institutional user of petroleum, the Pentagon is a significant part of the problem, generating greenhouse gasses equivalent to the emissions of the entire nation of Sweden. The U.S. military has an opportunity to reduce the risks associated with climate change — and thus its associated security threats — by reducing its role in creating greenhouse gas emissions. But action by the Pentagon alone would only be part of a larger solution that would require major societal changes.

The military has underscored the ways that climate change challenges its ability to operate. In 2014 the Pentagon offered a Climate Change Adaptation Roadmap that stressed the necessity of preparing for and adapting to climate change. A 2019 DOD report on issues arising from climate change noted that the U.S. military already experiences the effects of global warming at a large number of its installations. Impacts include recurrent flooding (53 installations); drought (43 installations); wildfires (36 installations); and desertification (six installations). The report states that vulnerability will only increase over the next twenty years.

The Pentagon’s response to the challenges of climate change has been to stress the need for military preparations — such as moving military bases and developing training and equipment to operate in changing climates.

National security planners expect the military services to play an increasing role supporting civil authorities in disaster relief missions. They are also concerned that climate–related natural disasters will undermine the ability of the U.S. military to operate. As sea levels rise, civilian infrastructure will be at risk. In September 2016, President Obama issued a National Security Memorandum that said, “[c]limate change and associated impacts on U.S. military and other national security-related missions and operations could adversely affect readiness, negatively affect military facilities and training [and] increase demands for Federal support to non–federal civil authorities.”

The Pentagon leaves a huge carbon footprint, so cutting its energy use and fostering alternative sources could have a positive impact in addressing climate change. In addition, if the United States reduced its imports of oil from the Persian Gulf, including fuel used to protect those imports, it would be able to dramatically reduce the size of the U.S. military presence in the region and the overall size of the military. As a consequence of spending less money on fuel and operations to provide secure access to petroleum, the United States could decrease total U.S. military spending and the size of the military, and reorient its economy to other more economically productive activities.

Savings from a more restrained strategy could be invested in alternative energy and other climate–friendly technologies and activities. The Pentagon’s role as a purchaser could also help reduce the cost of energy alternatives by creating the foundations of a reliable market.

The challenge posed by climate change is daunting: rising temperatures and sea levels and extreme weather will increase the frequency and intensity of natural disasters worldwide, exacerbate water and food insecurity, and increase the spread of disease.

The imperative for concerted action to address climate change could not be clearer. However, it is important to underscore that the Department of Defense cannot and should not take the lead on addressing climate issues writ large — that will involve new government regulations and investments, large-scale action by the private sector, and changes in consumer behavior, among other measures — an enormous societal effort grounded in civilian institutions. Addressing the climate crisis will require an unprecedented focus of attention and resources, perhaps beyond even the level reserved for military ventures like the war on terror. But freeing up resources by reducing the size of the military in line with a more realistic strategy can contribute to a solution. The gap between proposed investments in addressing the climate issue and continued increases in military spending is stark — investments in “clean energy technologies, manufacturing, and innovation” contained in the Inflation Reduction Act will run at an average of $37 billion per year over 10 years, just over 4 percent of the current proposal for annual spending on national defense.

Program

Countries/Territories

Entities

Citations

“Biden Wants $886 Billion Defence Budget With Eyes on Ukraine and Future Wars,” March 14, 2023, https://bdnews24.com/world/americas/asfknxnyy7. ↩

For the years 1948-2022 the chart depicts then-year Department of Defense Total Budget Authority, taken from Table 6-8 in The Department of Defense’s “National Defense Budget Estimates for 2023,” also known as the Green Book: https://comptroller.defense.gov/Portals/45/Documents/defbudget/FY2023/FY23_Green_Book.pdf.For 2023 and 2024, data are taken from the Fiscal Year 2024 National Defense Discretionary Budget Request: https://comptroller.defense.gov/Portals/45/Documents/defbudget/FY2024/FY2024_Budget_Request.pdf All years are adjusted for inflation, and shown in 2023 dollars, using the GDP Chained Price Index from OMB Historical Table 10.1: https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/budget/historical-tables. ↩

Letter from the Congressional Budget Office to House Speaker Kevin McCarthy, “CBO’s Estimate of the Budgetary Effects of H.R. 3746, the Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023,” May 30, 2023, https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2023-05/hr3746_Letter_McCarthy.pdf. ↩

Sustainable Defense: More Security, Less Spending, Report of the Sustainable Defense Task Force, Center for International Policy, June 2019, 30-31. https://static.wixstatic.com/ugd/fb6c59_59a295c780634ce88d077c391066db9a.pdf. ↩

U.S. Department of Defense, “2022 National Defense Strategy of the United States of America,” October 27, 2022, https://media.defense.gov/2022/Oct/27/2003103845/-1/-1/1/2022-NATIONAL-DEFENSE-STRATEGY-NPR-MDR.PDF. ↩