Peace Through Strength in Ukraine: Sources of U.S. Leverage in Negotiations

Executive Summary

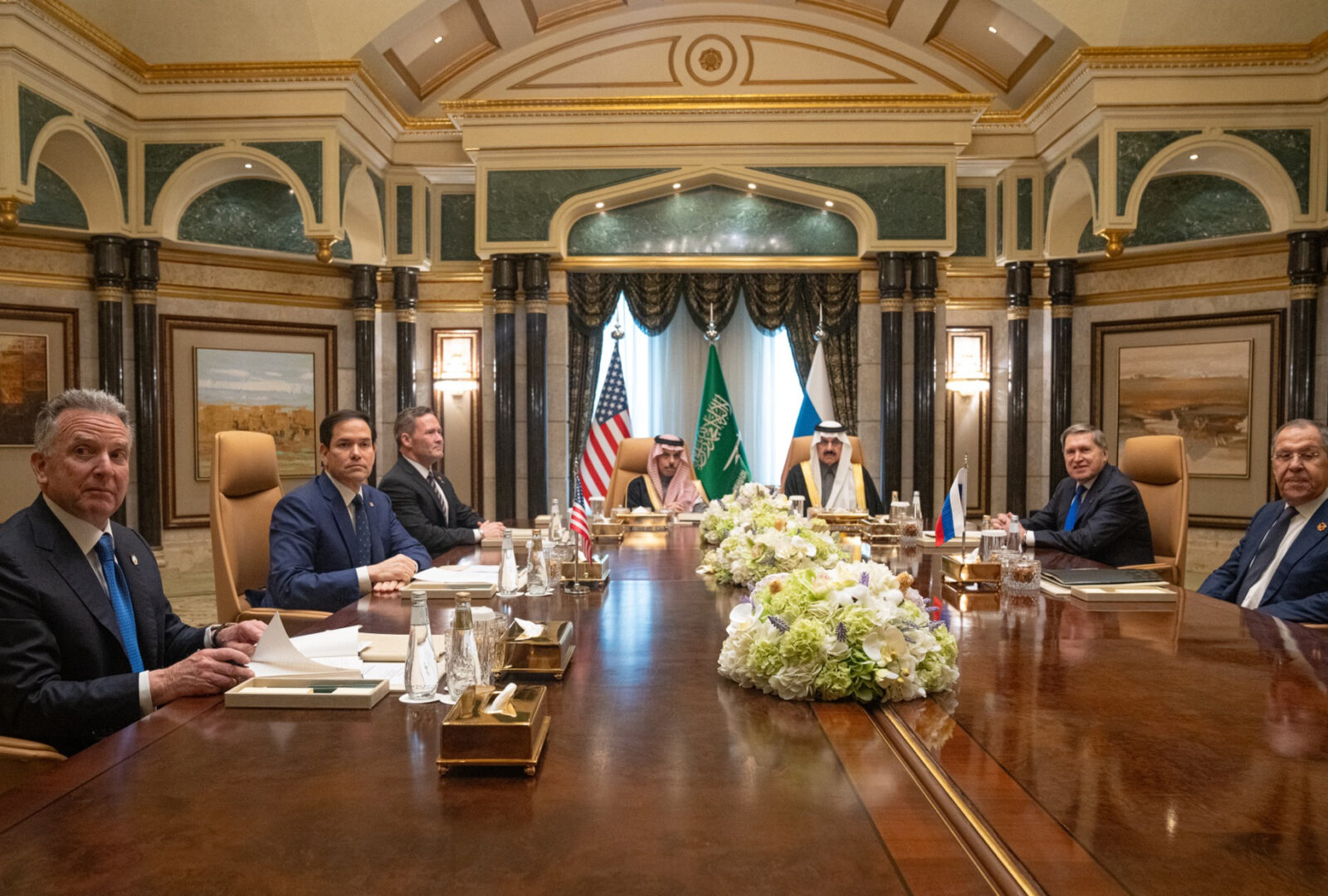

The key to American success in ending the war in Ukraine is to broaden, rather than narrow, the issues under negotiation. If American negotiators treat the war as a bilateral dispute between Russia and Ukraine and press both sides to agree to an immediate ceasefire, they are likely to fail.

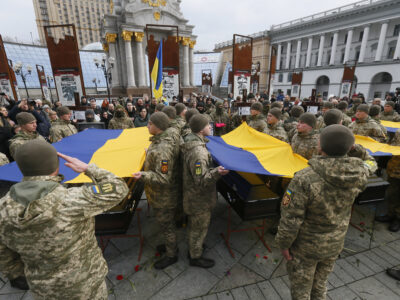

In a narrow negotiation, Russia has significant advantages because it has turned the conflict into a war of attrition in which its much greater population and much larger military industry are overwhelming Ukraine’s defenses. The United States and Europe lack the capacity to match Russia’s arms production or bridge the Russia–Ukraine manpower gap without direct conflict with Russia.

By contrast, if Washington recognizes that Moscow’s security concerns extend beyond Ukraine to the broader military threat posed by U.S. and NATO forces in Europe — a threat Russia cannot blunt by conquering Ukraine — the U.S. can employ leverage that Kyiv lacks in direct bargaining with Moscow.

Key Takeaways:

- The United States can expand or constrain its force posture in Europe depending on Russia’s willingness to compromise over Ukraine.

- The prospect of Russia’s return to Western diplomatic forums would accord with its self-image as a great power, provide it with a voice in a region it sees as vital to its security, and decrease its dependence on China. The first small step toward greater Russian inclusion would be a direct summit meeting between the U.S. and Russian presidents, but this should be offered only as an incentive for genuine progress toward ending the war in Ukraine.

- Sanctions relief is a key incentive to make a settlement stick. For Moscow to have a stake in peace, it must see benefits in compliance as well as the costs of violating settlement provisions. These positive and negative incentives are best captured through the conditional suspension of specific sanctions, as opposed to their unconditional removal.

- Inviting China’s special envoy on Ukraine to visit the United States and discuss a settlement — something Beijing sought but former President Biden refused to offer — would put pressure on President Vladimir Putin. A significant Chinese role in a postaccord reconstruction of Ukraine would both give China a stake in preserving peace and serve as a powerful disincentive for Putin to violate the terms of a settlement or reinvade.

- In exchanging a Western commitment to Ukraine’s permanent neutrality for a Russian commitment to support Ukraine’s E.U. membership, the West could use the accession process to bring Ukraine’s treatment of ethnic and linguistic minorities into conformity with E.U. standards, thereby addressing some stated Russian war aims.

Overview

Introduction

Success in negotiating a compromise settlement of the war in Ukraine will pivot on two factors: finding sufficient overlap among the core interests of the United States, Russia, Ukraine, and Europe; and employing America’s leverage over these players in ways that incentivize a compromise and penalize obstinance. The Biden administration misunderstood the leverage it had in forging a settlement, mistakenly believing that the key to success was a combination of maximizing Ukraine’s battlefield success while sanctioning Russia economically and diplomatically.

In fact, America can maximize its leverage in settlement talks by refocusing on the broader geopolitical context for the war: Russia’s objection to a NATO–centric European security order in which Russia has no place and its neighbors sooner or later become military partners of the United States.

To most effectively use American leverage and secure Ukraine, it is important to understand Russia’s broader geopolitical aims. While Russia is clearly willing to use aggression and violate international norms and laws to reach these aims, we argue that the aims themselves are based on Russian security on its periphery and not aggressive expansion and conquest for its own sake. Once the context is expanded from the battlefield within Ukraine to the overall question of Russia’s relation to the European security order, the U.S. has powerful cards to play — both in the areas of threats and incentives. These leverage points can be activated to pursue key U.S. aims ranging from a secure and European–aligned Ukrainian state to disrupting the increasing alignment between Russia and China.1

The search for a stable and lasting peace settlement to end the Ukraine War must also be founded on a recognition of certain inescapable realities. Neither Ukraine nor Russia will withdraw from territory that they currently hold; Ukraine will not abandon its desire to be part of the West socially, culturally, and economically; and Russia will not accept any settlement that allows Ukraine to become part of the West militarily.

Harmonizing these imperatives will not be easy. But both Washington and Moscow have a strong interest in reaching a deal that addresses Russia’s legitimate security concerns and, in return, leads to a halt in Russia’s military offensive and a comprehensive peace settlement minimizing the risk of future war.2Without such a deal, the U.S. and Europe would be forced to continue to provide massive military and financial aid to Ukraine indefinitely, while still facing the risk of Ukrainian collapse.3For its part, Russia would continue to suffer casualties, would experience more pressure on its economy, and would have no guarantee of victory absent more intensive mobilization, which would carry domestic political risks.4

It is the thesis of this brief that a stable and lasting settlement that supports a secure Ukraine is attainable if the U.S. makes full use of its leverage in the broader European security sphere.

Sources of U.S. leverage

In a broader negotiation over the European security order and the roles of Russia and Ukraine within it, the Trump administration has many cards to play. They fall broadly into the following categories:

Military leverage

The U.S. has significant leverage based not primarily on its support for the Ukrainian military, but on the dominant U.S. and NATO military position in Europe.

Under existing conditions, the United States and NATO should not end military support for Ukraine, which would almost certainly hasten Ukraine’s collapse and put Russia in a position to dictate, rather than negotiate, the terms of a settlement.5Continuing this aid is critical to slow Russia’s advances and allow time for negotiations. Nonetheless, new tranches of aid beyond what has already been pledged should be short-term commitments and should be focused on defensive weaponry — sending a not-so-subtle message from Washington to Kyiv that it must engage in good-faith diplomacy to settle the war or risk losing U.S. support altogether.

Although such aid is necessary for now, America’s military leverage over Russia does not flow from its ability to tilt battlefield conditions in Ukraine’s favor. Since the first year of the war, Russia has adapted tactics and developed technical countermeasures to compensate for America’s superior real-time intelligence and precision weaponry, turning the conflict into a war of attrition that plays to Moscow’s advantage.6The United States and Europe combined lack the industrial capacity to match Russia’s artillery production — a key factor in the war — and it would take years to produce air defense systems on the scale Ukraine requires to defend its cities and critical infrastructure against Russian air, missile, and drone attacks.7The only way that the United States and NATO could overcome Russia’s vast manpower advantages over Ukraine would be through direct military intervention — a step that could easily lead to nuclear war.

Rather, our military leverage to end the conflict lies beyond Ukraine — in Russia’s broader concerns about threats posed by the NATO alliance, which has doubled in size since the end of the Cold War and grown still larger since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. NATO now shares a border with Russia that, at 1,700 miles, is almost as long as that between Mexico and the United States. NATO also has a very substantial conventional arms advantage over Russia, and this will only increase as Europe rearms.8

Russia’s December 2021 demand prior to the full-scale Ukraine invasion that NATO withdraw forces from its postexpansion borders reflects security concerns that have likely become even more urgent in light of additional NATO expansion after 2022.9While Russia’s 2021 demand was far too sweeping for NATO to meet, the initial Russian focus on NATO deployments shows how many cards the U.S. has to play in this area.

The question of limits on Ukraine’s own military holdings was a central issue in Turkish–mediated settlement talks between Russian and Ukrainian negotiators early after Russia’s invasion. Russia insisted on stringent quantitative and qualitative caps; Ukraine pressed its need for a capable self-defense force coupled with security guarantees from a range of other states.

When the Istanbul talks broke down in mid–April 2022, the two sides remained far apart on force limitations. The Ukrainians called for a peacetime army of 250,000; the Russians insisted on a maximum of 85,000 — considerably smaller than the standing army Ukraine had before the invasion in 2022.10The Ukrainians wanted 800 tanks, while the Russians insisted on less than half that number. The difference between limitations on the range of missiles each side advocated was even wider: the Ukrainians proposed a limit of 280 kilometers, and the Russians demanded 40 kilometers — hardly more than an advanced artillery system.11

It is possible — even likely — that the gap between the Ukrainians and Russians on this matter is even greater today than it was during the Istanbul talks in 2022. Putin has said that Istanbul should remain the framework for a settlement, but nearly three subsequent years of bloodshed will likely have resulted in a stiffening of Russian demands.12For its part, Ukraine’s estimate of the force it requires for self-defense is likely to be much larger if NATO or its individual members remain reluctant to commit to hard security guarantees against future Russian invasion.

By itself, Ukraine has little leverage over Russia on this matter, particularly as its battlefield prospects dim.13But the United States and NATO do. As discussed above, NATO’s military posture is critical to Russian security concerns.14U.S. negotiators can point out that, should Russia balk at reasonable force limitations in Ukraine (which should also require reciprocal limits on Russian deployments opposite Ukraine), the West would be forced to increase the size of its own forces around Ukraine and bordering Russia. Our willingness to constrain the range of ground- and air-launched missiles that we provide to Ukraine should also be conditioned on Russia’s willingness to agree to reasonable caps on its own forces and Ukrainian forces.

Along these lines, discussion of force limits and weapons holdings within the Ukraine negotiations will open the broader question of modifying the Adapted Treaty on Conventional Forces in Europe, CFE, which was signed in 1999 and ratified by Russia, but never ratified by the United States.15Russia is probably not eager to bear the high costs of maintaining a standing army sufficient to counter the combined forces of NATO, whose membership has almost doubled in size since the adapted CFE treaty was signed. Holding out the prospect of broader talks on conventional forces in Europe could serve as an incentive for Moscow to strike a reasonable compromise with Ukraine over force limitations.

Adding to the potential pressure on Russia, in 2026 the United States plans to station intermediate-range, nuclear-capable missiles in Germany for the first time since the 1980s.16NATO’s 1983–85 deployment of Pershing II missiles in Europe to counter the Soviet Union’s SS-20s prompted grave fears in Moscow over hair-trigger warning times and the potential for nuclear “decapitation.” Such fears ultimately led to the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty, which banned intermediate-range missiles as a class and helped lead to broader improvements in U.S.–Soviet relations. Similarly, signaling a willingness to reconsider or expand the planned deployments for 2026 could significantly affect Russia’s openness to compromise over Ukraine.

Diplomatic engagement

One of the greatest sources of American leverage flows from a commodity that is as intangible as it is important: respect.

Russia considers itself a great power, and it doubts that it could survive for long were it not one given its broad geographic expanse, its history of foreign invasion, and its multiethnic composition.17 But Russians have long been frustrated by the West’s reluctance to accord the respect they feel their status merits and their security demands. This frustration has in recent years turned into anger as U.S. and European officials have spoken openly about inflicting a “strategic defeat” on Russia, at times even expressing hopes for regime change.18

As doors to Western institutions have closed — largely due to Russia’s own counterproductive behavior — Moscow has grown increasingly dependent on its relations with China and the Global South.19But most Russians find these circumstances far from ideal. They have little desire to play junior partner to a rising China, and they consider themselves more European than Asian in their culture and values.

From Moscow’s perspective, finding a way back into Western forums would accord with Russia’s self-image as a great power, provide it with a voice in a region it perceives as critical to its security interests, and offer greater room for maneuver in its relations with China. But they have for years doubted that the West has any interest in such engagement. The first small step toward greater Russian inclusion would be a direct summit meeting between the U.S. and Russian presidents, but this should be offered only as an incentive for genuine progress toward ending the war in Ukraine.

Arrangements for implementing an Ukraine settlement may also offer a creative means for Moscow gradually to acclimate the West to growing Russian involvement in European security matters. In the draft Istanbul accord, Ukraine proposed an international group of guarantors that would include, among others, the United States, Russia, the U.K., France, Germany, Italy, Poland, and Turkey.20Such a group could initially oversee implementation of a settlement and resolve the disputes that will inevitably arise over its provisions.Over time, Russia’s good-faith negotiation and implementation of a settlement in Ukraine could allow that group to expand its discussions to include security matters in other parts of Europe where conflicts with Russia might emerge. The prospect of membership in such a body could be a significant incentive for Russia to make concessions on Ukraine’s borders and pursue a broader détente with the West. Rather than trading land for peace — a negotiating formula that was once the conceptual basis for settling the Israel–Palestine conflict — the Western approach could offer a path toward gradual Russian inclusion in European councils in return for good-faith implementation of a settlement in Ukraine.21

Economic leverage

Sanctions relief is a key leverage point in the overarching incentive structure to make a settlement stick. For Moscow to have a stake in peace, it must internalize both the benefits of compliance and the costs of violating provisions agreed upon with Ukraine and the West.22These positive and negative incentives are best captured through the permanent, conditional suspension of specific sanctions, as opposed to their unconditional removal. The West would commit to lift and not reimpose certain sanctions pending Russia’s commitment to mutually agreed-upon peace provisions, such as respecting Ukraine’s territorial integrity or not interfering with the legitimate activities of peacekeepers in Ukraine. These agreements would be bolstered with verification protocols, which could lead to the reimposition of sanctions.

For this regime to be effective, it must be established and enforced in a piecemeal fashion reflecting the diverse scope of prospective agreements between the U.S. and Russia, Ukraine and Russia, and European states or the E.U. and Russia; the reimposition of certain sanctions in case of noncompliance in a specific area does not imply the reinstatement of all sanctions. Compartmentalizing sanctions relief and compliance across multiple subagreements disincentivizes Russian leaders from adopting the dangerous zero-sum thinking that there is no difference between violating one or all of the peace provisions. A graduated approach would force Russia to weigh the costs of partial noncompliance against the benefits of other sanctions that have not yet been reimposed, reducing the risk of an isolated violation spiraling into a breakdown of the wider peace framework and increasing the chances of successfully bringing Russia back into compliance.

Related to sanctions is the issue of the $300 billion worth of Russian assets in the E.U. and U.S. that were frozen as a result of the Ukraine invasion.23While the revenue from these assets is already being tapped to finance the Ukrainian military, they should not be fully seized outside of the context of a negotiated agreement.24Instead, they should be saved as leverage during talks. Securing Russia’s explicit agreement for these assets to become part of an international Ukraine reconstruction fund would avoid the chilling effect that unilateral seizure would produce on international investors.25 The use of such funds, which have probably already been written off by Russia, would be preferable to Russia than reparations drawn directly from its current economy. Offering the potential that a portion of these funds may potentially be allocated to regions under de facto Russian control would also give Moscow an additional incentive to comply with a peace deal.

A broader advantage of the use of sanctions relief as negotiating and enforcement leverage for an agreement is its relation to economic normalization in Europe. Such normalization is significant not just as a bargaining chip vis-à-vis Russia, but as a boon to beleaguered E.U. states, serving to incentivize their support for a compromise to end the war. Europe cannot be expected to assume greater charge of its defense and of Ukraine’s postwar reconstruction while its economies continue to suffer from blowback produced by the international sanctions on Russia.

Europe’s sustained stability and prosperity are best served by developing a format for energy normalization that would see renewed Russian energy exports into Europe, potentially through a resumption of Russian gas flows through the Nord Stream pipelines.26The U.S., Russia, and E.U. partners should explore optimal terms on which these gas exports can resume. U.S. acquisition and partial ownership of Nord Stream 2 could minimize Western concerns of Moscow leveraging its energy exports as a tool of geoeconomic influence, reassure European partners, and serve U.S. financial interests. Other formats — including Gazprom ownership subject to mutually agreed E.U. oversight and regulations — can also be explored during negotiations.27

Ukraine’s deposits of strategic minerals, which include lithium, uranium, titanium, graphite, and rare earth metals, offer an opportunity for creative diplomacy in incentivizing both Russia and Ukraine to reach a compromise settlement of the war. Many of these mineral deposits lie in Russian–controlled parts of Ukraine, but Russia is not well-positioned to process many of these raw minerals, needing both capital and technology to get them to end-user markets.28It is far preferable for the United States to incentivize Russian sales of these minerals for processing and use in the West than in China.

There are potentially many ways the terms of a settlement could incentivize both Ukrainian and Russian exports of these minerals to the West. One possibility would be for the United States to offer technology for processing to both Ukraine and Russia with the proviso that exports of refined products go to Western end-users. Capital for both Ukrainian and Russian mining and processing of these minerals might come from seized Russian assets, again on the premise that exports go to the West.

The power of the E.U. accession process

Discussions of Ukraine’s future have often assumed that Ukraine would have to be highly militarized and under permanent threat of conflict with Russia.29However, an effective use of U.S. leverage could secure a future for a neutral but European–aligned Ukraine.

Such a future could combine a path to E.U. membership with military neutrality along the lines of Finland or Austria during the Cold War.30E.U. membership would satisfy the Ukrainian need for a decisive orientation toward the West and social and political membership in the broader European community. At the same time, military neutrality could address Russian concerns about a hostile foreign military on their border. Russia will clearly not welcome E.U. membership for Ukraine. However, we believe that a resolute use of U.S. and NATO leverage around military and economic issues, as described above, along with addressing the most fundamental Russian security concerns around Ukraine’s military orientation, would make such membership achievable within the context of a peace agreement.

E.U. accession would involve Ukraine meeting E.U. membership requirements around economic, social, and political institutions and policies. Given Ukraine’s poverty, reputation for corruption, and the political and economic fallout of the war, meeting E.U. requirements will not be simple and will depend in part on reconstruction efforts.31However, the accession process also offers opportunities for addressing one of the thorniest issues around negotiations — namely, the Russian demand for the “denazification” of Ukraine. This is perhaps the most difficult of all the issues involved in the peace process, because — unlike NATO membership or European security — it falls entirely within the purview of Ukrainian domestic law, and only the Ukrainian government and parliament can ratify any agreement around the political and social changes necessary for it.

However, since the Russian government has never defined in detail what it means by its demand that Ukraine “denazify,” there are grounds for optimism that, in return for Moscow and Washington reaching a satisfactory agreement on security issues, Moscow will reduce its demand for “denazification” to an acceptable level.32

Russian demands cover two areas: an end to Ukrainian extreme nationalism, and constitutional guarantees for Russian language and cultural rights within Ukraine. Two potentially fruitful approaches for U.S. negotiators are to render commitments in this area acceptable to Ukraine by making them reciprocal (i.e., applicable to both Russia and Ukraine), and to make Ukrainian moves in these directions part of its process of accession to the European Union rather than as concessions to Russia.

Russian hardliners have defined “denazification” as regime change, which is both totally unacceptable for the U.S. and unachievable by Russia. However, the Austrian State Treaty of 1955, which established Austrian neutrality, contains a clause banning Nazi parties and symbols, as does the German constitution.33The introduction of such a clause into the Ukrainian constitution may be an acceptable compromise.

The E.U. accession process would put leverage on Ukraine to reach an acceptable compromise on minority rights. Minority rights are enshrined in the European Union’s acquis communautaire and in the Council of Europe’s Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities that aspirants to join the E.U. are required to sign and adhere to (though they have been flagrantly violated by Latvia and Estonia).34Adherence is monitored by several supervisory bodies of the Council of Europe.35

Moreover, under pressure from Hungary and the E.U., Ukraine has in fact guaranteed such rights to a range of small national minorities in line with recommendations of the European Council’s Venice Commission, but excluded the huge Russian minority (illegitimately, though for obvious political reasons).36As part of a peace settlement and its E.U. application, Ukraine should be required to observe consistency in this area, and to end its campaign against Russian cultural and historical monuments in Ukraine.

Advancing other strategic goals

Just as American leverage in negotiations to end the war flows from issues beyond the narrow Russian–Ukrainian relationship, Washington can use the settlement process as leverage to pursue strategic objectives that extend beyond the Ukraine conflict itself. In an increasingly multipolar world where the rise of Chinese power has become America’s foremost foreign policy challenge, Washington needs Europe to play a more significant role as a capable counterweight to Russia. The United States also needs to exploit divergent interests between Moscow and Beijing rather than continuing to incentivize a Chinese–Russian partnership that is hostile to American interests. Both these objectives can be advanced through the Ukraine settlement process.

Playing the China card

Ukraine is a small but meaningful point of friction between Russia and China. Beijing undoubtedly sympathizes with Putin’s concerns about NATO expansion, which Chinese officials and leading Chinese experts cite as the primary cause of the war.37They certainly do not want Russia to lose, which from their perspective would enable an invigorated West to refocus its resources and attention on China, while crippling Russia’s ability to help Beijing deal with Western pressure.38But, at the same time, Beijing is clearly not happy about Russia’s territorial grab in Ukraine, which plays on China’s memories of Western invasion and occupation. Chinese officials have also been outspoken in warning Russia against the dangers of nuclear saber-rattling in the war.39

China’s appointment of a special Ukraine peace envoy probably flows not only from this mix of concerns, but also from its hope that facilitating a compromise settlement could pay dividends for China’s image in Europe — a market that is growing in importance to Beijing as trade with the United States comes increasingly under threat.40China also wants to blunt momentum toward growing NATO involvement in Asia, and it likely sees support for peace in Ukraine as a means of combating anti–Chinese sentiment in Europe. Washington can exploit this Chinese ambivalence — not to seek Chinese help in mediation but to spur Russia toward good-faith negotiations and to ensure that it complies with the terms of a settlement.

Inviting China’s special envoy on Ukraine to visit the United States and discuss a settlement — something Beijing sought but Biden refused to offer — would put pressure on Putin, as he would be hard-pressed to refrain from engagement in a process that his primary partner supports. Moreover, a significant Chinese role in the postaccord reconstruction of Ukraine would give China a stake in preserving peace in Ukraine and serve as a powerful disincentive for Putin to violate the terms of a settlement or reinvade. In narrowing Putin’s room to maneuver on Ukraine through American engagement with China, Washington will not drive a wedge between Moscow and Beijing, but it will highlight their divergent interests in Europe and reduce their incentives for making common cause against the United States.

Strengthening Europe

With regard to Europe itself, the war in Ukraine has exposed some uncomfortable realities. A Europe whose industries are unable to produce the large volumes of weaponry and ammunition necessary for sustained warfare, and which lacks significant logistical capabilities and unified military leadership, cannot serve as a strategic asset for the United States in counterbalancing and deterring Russia through its own resources.41Overreliance on American patronage has also allowed European diplomacy to become insolvent, seeking end goals — including Russia’s capitulation and internal transformation — that are far beyond its means and arguably at odds with its actual strategic interests.

In seeking a settlement in Ukraine, the United States should incorporate incentives for Europe to address these deficiencies. In part, this can be done by making clear that Europe will bear the primary military responsibility for deterring and, if necessary, responding to a new Russian invasion of Ukraine.42This prospect should focus Europe’s attention on the yawning gap between its current capabilities and those necessary for success in this task, incentivizing much greater military production and rationalizing its weapons programs.

This responsibility should also encourage a more realistic European approach to diplomacy with Russia.43European stability is a precondition for an expanded European geopolitical role. Although the United States should play the leading role in parlaying negotiations with Russia over Ukraine into broader discussions about European security, our allies will need to engage in talks over codes of conduct and confidence and security-building measures aimed at preventing or defusing conflicts in such hot spots as Belarus, Kaliningrad, Moldova, the Balkans, and beyond. A Europe riven by crises and divided by a modern variation of the Iron Curtain will be a weak and preoccupied Europe, unable to play a constructive and stabilizing role in the evolving multipolar order.

Program

Entities

Citations

Gunnar Wiegand, Natalie Sabanadze, and Abigaël Vasselier, “China–Russia Alignment: A Threat to Europe’s Security,” German Marshall Fund, June 26, 2024, https://www.gmfus.org/news/china-russia-alignment-threat-europes-security. ↩

Anatol Lieven, “U.S. Plan for a Quick Ukraine Ceasefire Is a Non-Starter,” UnHerd, February 11, 2025,

https://unherd.com/newsroom/us-plan-for-a-quick-ukraine-ceasefire-is-a-non-starter/. ↩

“Amid Talk of a Ceasefire, Ukraine’s Front Line Is Crumbling,” The Economist, January 27, 2025, https://www.economist.com/europe/2025/01/27/amid-talk-of-a-ceasefire-ukraines-front-line-is-crumbling. ↩

David Lubin, “Russia’s Economic Dilemmas Give Trump Important Leverage in Negotiations on Ukraine. But Will He Use It?” Chatham House, January 10, 2025,

https://www.chathamhouse.org/2025/01/russias-economic-dilemmas-give-trump-important-leverage-negotiations-ukraine-will-he-use-it. ↩

David Vergun, “Official Says Without U.S. Funding, Ukraine’s Defense Will Likely Collapse,” U.S. Department of Defense, DoD News, February 16, 2024,

https://www.defense.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/Article/3679991/official-says-without-us-funding-ukraines-defense-will-likely-collapse/. ↩

Mark Episkopos, “No Magic U.S. Weapon Left for Offensive Ukraine Victory,” Responsible Statecraft, February 1, 2024, https://responsiblestatecraft.org/us-weapons-ukraine/. ↩

John Psaropoulos, “Russia Races Ahead of NATO in Weapons Production for Ukraine War: SIPRI,” Al Jazeera, December 2, 2024,

https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/12/2/russia-races-ahead-of-nato-in-weapons-production-for-ukraine-war-sipri. ↩

George Beebe, Mark Episkopos, and Anatol Lieven, “Right-Sizing the Russian Threat to Europe,” Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft, July 8, 2024, https://quincyinst.org/research/right-sizing-the-russian-threat-to-europe/#. ↩

Andrew Roth, “Russia Issues List of Demands It Says Must Be Met to Lower Tensions in Europe,” The Guardian, December 17, 2021, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/dec/17/russia-issues-list-demands-tensions-europe-ukraine-nato. ↩

Samuel Charap and Sergey Radchenko, “The Talks That Could Have Ended the War in Ukraine,” Foreign Affairs, April 16, 2024, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/ukraine/talks-could-have-ended-war-ukraine. ↩

Charap and Radchenko, “The Talks.” ↩

Kateryna Denisova, “Putin Claims Istanbul Peace Plan Draft Still ‘on Table’ for Talks Between Russia and Ukraine,” Kyiv Independent, July 4, 2024, https://kyivindependent.com/putin-claims/. ↩

George Beebe, “Kicking the Can Down the Crumbling Road in Ukraine,” Responsible Statecraft, April 24, 2024, https://responsiblestatecraft.org/ukraine-aid-2667871647/. ↩

Beebe, Episkopos, and Lieven, “Right-Sizing the Russian Threat.” ↩

“The Conventional Armed Forces in Europe (CFE) Treaty and the Adapted CFE Treaty at a Glance,” Arms Control Association, November 2023, https://www.armscontrol.org/factsheets/conventional-armed-forces-europe-cfe-treaty-and-adapted-cfe-treaty-glance. ↩

“U.S. to Start Deploying Long-Range Weapons in Germany in 2026,” Reuters, July 10, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/business/aerospace-defense/us-start-deploying-long-range-weapons-germany-2026-2024-07-10/. ↩

Dmitri Trenin, Should We Fear Russia? (Cambridge: Polity, 2016). ↩

“NATO Chief Declares ‘Strategic Defeat’ for Putin But Ukraine Urges Caution,” Kyiv Post, December 23, 2024, https://www.kyivpost.com/post/25860. ↩

Felix K. Chang, “China’s and India’s Relations with Russia after the War in Ukraine: A Dangerous Deviation?” Foreign Policy Research Institute, April 5, 2023,

https://www.fpri.org/article/2023/04/chinas-and-indias-relations-with-russia-after-the-war-in-ukraine-a-dangerous-deviation/. ↩

Charap and Radchenko, “The Talks.” ↩

Hope O’Dell, “What Is the Land-for-Peace Principle Some Hope Will Resolve Conflict in the Middle East?” Chicago Council on Global Affairs, February 22, 2024, https://globalaffairs.org/bluemarble/what-land-peace-principle-some-hope-will-resolve-conflict-middle-eas. ↩

Ian Proud, “Russia Sanctions Are Stone Cold Leverage. Let’s Use It,” Responsible Statecraft, January 25, 2025, https://responsiblestatecraft.org/lift-sanctions-on-russia/. ↩

Jackie Northam, “A Debate Is Centered on What to Do with $300 Billion in Seized Russian Assets,” NPR, March 11, 2024, https://www.npr.org/2024/03/11/1237398076/a-debate-is-centered-on-what-to-do-with-300-billion-in-seized-russian-assets. ↩

Alan Rappeport and Jenny Gross, “G7 Finalizes $50 Billion Ukraine Loan Backed by Russian Assets,” The New York Times, October 23, 2024, https://www.nytimes.com/2024/10/23/business/g7-ukraine-loan-russian-assets.html. ↩

Creon Butler, “Confiscating Sanctioned Russian State Assets Should Be the Last Resort,” Chatham House, May 1, 2024, https://www.chathamhouse.org/2024/05/confiscating-sanctioned-russian-state-assets-should-be-last-resort. ↩

Mark Episkopos, “How Trump Can Leverage Russian Energy for Peace in Europe,” The American Conservative, January 19, 2025, https://www.theamericanconservative.com/how-trump-can-leverage-russian-energy-for-peace-in-europe/. ↩

Christopher M. Matthews, “A Miami Financier Is Quietly Trying to Buy Nord Stream 2 Gas Pipeline,” The Wall Street Journal, November 21, 2024, https://www.wsj.com/business/energy-oil/a-miami-financier-is-quietly-trying-to-buy-nord-stream-2-gas-pipeline-f43dd85d. ↩

Howard Altman, “Ukrainian Minerals for Arms Deal Complicated by Russian Control of Key Territories,” The War Zone, February 5, 2025, https://www.twz.com/news-features/ukrainian-minerals-for-arms-deal-complicated-by-russian-control-of-key-territories. ↩

Max Bergmann, “How to Support Ukraine: Peace Will Require Ukrainian Strength,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, December 16, 2024, https://www.csis.org/analysis/how-support-ukraine-peace-will-require-ukrainian-strength. ↩

Anatol Lieven and Alex Little, “Ukraine Should Take a Page out of Finland’s Fight with Stalin,” Responsible Statecraft, December 21, 2023, https://responsiblestatecraft.org/ukraine-neutrality/; James Carden, “What the 68-Year-Old Austria Treaty Could Tell Us about Ukraine Today,” Responsible Statecraft, May 15, 2023, https://responsiblestatecraft.org/2023/05/15/what-the-68-year-old-austria-treaty-could-tell-us-about-ukraine-today/. ↩

“Corruption Looms Over Ukraine’s Massive Reconstruction Effort,” France 24, November 11, 2024, https://www.france24.com/en/live-news/20241114-corruption-overshadows-ukraine-s-multi-billion-reconstruction-progam. ↩

“Institute for the Study of War: Putin Renews Demand for Ukrainian ‘Denazification,” Boston Council on Foreign Affairs, December 29, 2024, https://bcfausa.org/institute-for-the-study-of-war-putin-renews-demand-for-ukrainian-denazification/. ↩

“State Treaty for the Re-Establishment of an Independent and Democratic Austria (Vienna, 15 May 1955),” Centre Virtuel de la Conaissance sur l’Europe, May 15, 1955, https://www.cvce.eu/en/obj/state_treaty_for_the_re_establishment_of_an_independent_and_democratic_austria_vienna_15_may_1955-en-5c586461-7528-4a74-92c3-d3eba73c2d7d.html; Dan Glaun, “Germany’s Laws on Hate Speech, Nazi Propaganda & Holocaust Denial: An Explainer,” PBS Frontline, July 1, 2024, https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/frontline/article/germanys-laws-antisemitic-hate-speech-nazi-propaganda-holocaust-denial/. ↩

“European Union Acquis,” EUR–Lex, accessed January 24, 2025, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=LEGISSUM:acquis#; “National Minorities,” Council of Europe, February 1, 1995, https://www.coe.int/en/web/minorities. ↩

“Ukraine: Opinion on the Law on National Minorities (Communities),” Venice Commission, June 2023, https://www.venice.coe.int/webforms/documents/default.aspx?pdffile=CDL-AD(2023)021-e. ↩

Tadeusz Iwański and Andrzej Sadecki, “Ukraine–Hungary: The Intensifying Dispute over the Hungarian Minority’s Rights,” Centre for Eastern Studies, August 14, 2018, https://www.osw.waw.pl/en/publikacje/osw-commentary/2018-08-14/ukraine-hungary-intensifying-dispute-over-hungarian-0; Marcin Jędrysiak and Krzysztof Nieczypor, “Ukraine: Another Amendment to the Law on National Minorities,” Centre for Eastern Studies, December 13, 2023, https://www.osw.waw.pl/en/publikacje/analyses/2023-12-13/ukraine-another-amendment-to-law-national-minorities. ↩

“China Blames NATO for Pushing Russia–Ukraine Tension to ‘Breaking Point,’” Reuters, March 9, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/china-blames-nato-pushing-russia-ukraine-tension-breaking-point-2022-03-09/. ↩

John Haltiwanger, “China Doesn’t Want Russia to Lose in Ukraine. But Beijing’s Endgame Is Murky,” Business Insider, March 4, 2023, https://www.businessinsider.com/china-doesnt-want-russia-lose-ukraine-but-its-endgame-murky-2023-3. ↩

Brendan Cole, “China Told Putin Not to Use Nuclear Weapons, Blinken Says,” Newsweek, January 4, 2025, https://www.newsweek.com/russia-nuclear-china-blinken-2009670. ↩

Olesia Safronova, “China Envoy Li Hui Visits Ukraine and Meets With Zelenskiy Aide,” Bloomberg, March 7, 2024, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-03-07/china-envoy-li-hui-visits-ukraine-and-meets-with-zelenskiy-aide. ↩

Alexandr Burilkov and Guntram B. Wolff, “Europe Stands Increasingly Alone on Defence Production and Needs to Act,” Bruegel, October 31, 2024, https://www.bruegel.org/first-glance/europe-stands-increasingly-alone-defence-production-and-needs-ac. ↩

Ivanna Kostina and Kateryna Tyschenko, “Trump’s Adviser Says Europe Should Take On Ukraine’s Security Guarantees,” Ukrainska Pravda, February 9, 2025, https://www.pravda.com.ua/eng/news/2025/02/9/7497436/. ↩

Tom Graham, “From the Ukraine Conflict to a Secure Europe,” Council on Foreign Relations, September 2024, https://www.cfr.org/report/ukraine-conflict-secure-europe#chapter-title-0-4. ↩