The Diplomatic Path to a Secure Ukraine

Executive Summary

Conventional wisdom holds that a negotiated end to the Ukraine war is neither possible nor desirable. This belief is false.

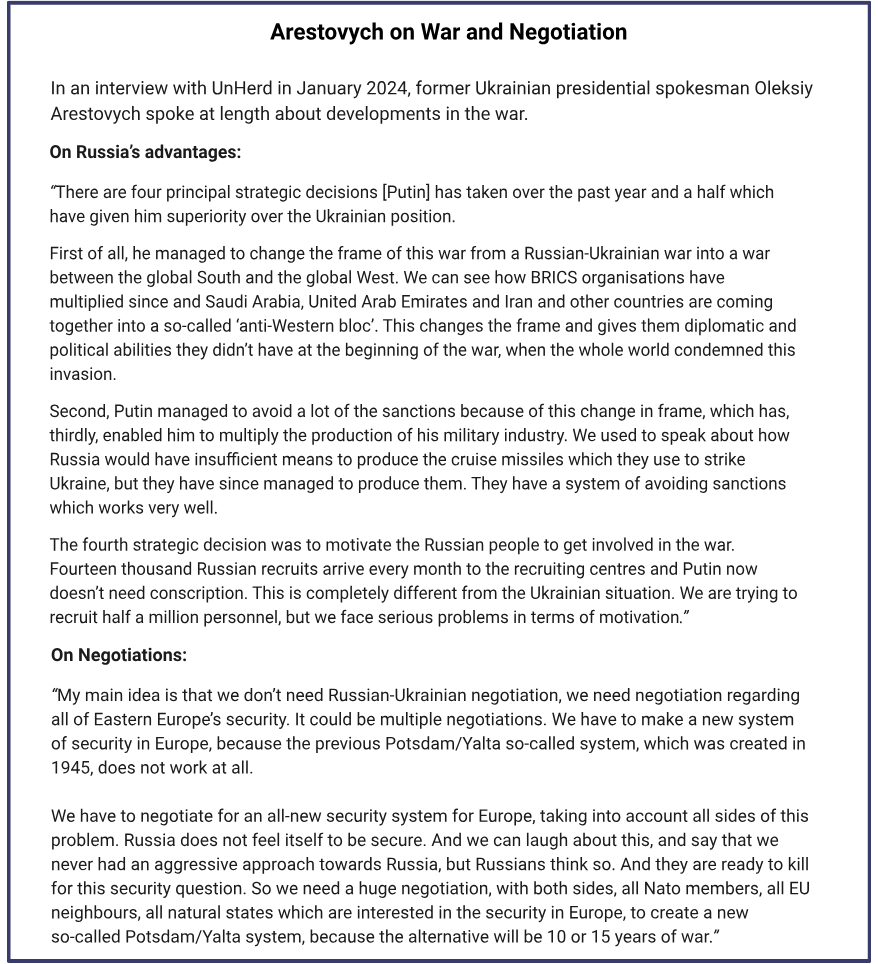

It is also extremely dangerous for Ukraine’s future. The war is not trending toward a stable stalemate, but toward Ukraine’s eventual collapse. Russia has corrected many of the problems that plagued its forces during the first year of fighting and adopted an attrition strategy that is gradually exhausting Ukraine’s forces, draining American military stocks, and sapping the West’s political resolve. Sanctions have not crippled Russia’s war effort, and the West cannot fix Ukraine’s acute manpower problems absent direct intervention in the war. Ukraine’s best hope lies in a negotiated settlement that protects its security, minimizes the risks of renewed attacks or escalation, and promotes broader stability in Europe and the world.

Skeptics counter that Russia has no incentive to make meaningful concessions in a war it is increasingly winning. But this belief underestimates the gap between what Russia can accomplish through its own military efforts and what it needs to ensure its broader security and economic prosperity over the longer term. Russia can probably achieve some of its war aims by force, including blocking Ukraine’s membership in NATO and capturing much of the territory it regards as historically and culturally Russian. But Russia cannot conquer, let alone govern, the majority of Ukraine, nor can Russia secure itself against the ongoing threats of Ukrainian sabotage or potential NATO strikes absent a costly permanent military buildup that would undermine its civilian economy. Reducing the deep dependence on China created by the invasion will also sooner or later require Russia to seek some form of détente with the West.

As a result, the United States has significant leverage for bringing Russia to the table and forging verifiable agreements to end the fighting. But this leverage will diminish over time. The United States should therefore quickly challenge Putin to make good on his insistence that Russia is willing to negotiate by publicly supporting calls from China, Brazil, and other key Global South actors for talks to end the war. And to help build trust and bolster dialogue, American officials should reach out to Russian representatives through both formal channels and a strictly confidential “back channel” that would facilitate sensitive discussions. Given deep Russian doubts about U.S. intentions, our outreach will have to include signals that we are prepared to discuss Moscow’s concerns about NATO expansion in the context of a Ukraine settlement.

Ukraine’s best hope lies in a negotiated settlement that protects its security, minimizes the risks of renewed attacks or escalation, and promotes broader stability in Europe and the world.

No settlement will endure unless Ukraine, Russia, and the West all see it as sufficiently serving their interests and as preferable to continued war. But we need not and should not simply trust that all parties will abide by its terms. Moscow and Washington have decades of useful Cold War experience in constructing, implementing, and monitoring a wide range of security agreements despite mutual distrust and broader geopolitical competition. While formidable, the obstacles to success are not insurmountable.

By combining defensive aid to Ukraine with a vigorous diplomatic offensive, the United States could secure independence for the vast bulk of Ukraine, provide a viable path toward its prosperity, and mitigate the dangers of long-term confrontation with Russia in Europe. This would not constitute a complete victory, but it would still be a monumental achievement.

Introduction

Over the course of two years, the war in Ukraine has gone through several major cycles of action and reaction. The first took place immediately after Russia’s large–scale invasion, when Ukraine quickly stymied Russia’s gambit to storm Kyiv and overwhelm Ukrainian defenses with simultaneous attacks from the north, east, and south. A series of embarrassing and largely self–inflicted failures forced the Russian high command to shift course and refocus efforts on capturing territory in Ukraine’s east and south, where the Russians made only modest advances over the course of several months. Whatever else happened in the war thereafter, it appeared unlikely that Putin’s army would ever raise the Russian flag over Kyiv.

The war shifted again in the latter part of 2022. Ukraine was receiving more and more tranches of precision Western weaponry to pair with the real–time intelligence it was gathering with American help. Effective Ukrainian air defenses discouraged the Russian air force from flying over Ukrainian territory and exploiting its enormous numerical advantages in the skies. Ukrainian commanders identified and exploited thinly–manned portions of Russian lines and scored spectacular victories in Kherson and Kharkiv. As winter weather forced a pause in the ground campaign, Ukraine had clear momentum in the war, and it appeared to many observers that the combination of Ukrainian battlefield grit and Western high–technology could ultimately force Putin to sue for peace.

Russia adapted yet again, however. In late 2022, Putin ordered what he called a “partial mobilization,” adding more than 300,000 troops to Russia’s depleted invasion force and putting Russian factories on a war footing. Meanwhile, Russian forces in the Donbas and south dug in, building formidable multi–echeloned defensive lines of tank traps, ditches, minefields, and underground shelters. Throughout the winter, Russia launched wave after wave of missile and drone strikes on Ukrainian energy infrastructure, thereby draining Ukraine of air defense munitions. Putin, it appeared, had shifted to an attrition strategy, betting that Russia’s numerical advantages in population and military production would eventually exhaust Ukraine’s resources and the West’s patience, while minimizing the risks of direct clashes with NATO.

This strategy has largely succeeded. Ukraine’s failed “counteroffensive” in 2023 and subsequent move to what it calls an “active defense” strategy marked the end of its hopes for recapturing large amounts of Russian–occupied territory. Russia demonstrated over the course of last year that it had learned from its early mistakes on the battlefield, adapted to the challenges posed by Western high technology, and advanced its own capabilities in drone warfare and electronic countermeasures.1 At the war’s two-year mark Russia has clear momentum, and Ukraine has few apparent means to regain the battlefield initiative and force Russian capitulation.

A failure to recognize the realities of this phase of the conflict carries grave risks for Ukraine’s future and for U.S. strategic interests. While the battlefield situation currently appears to be at a stalemate, the buildup of Russian forces in Ukrainian territory carries a risk of sudden military collapse for Ukraine. Even if this worst–case scenario does not occur, Ukraine cannot reasonably be expected to develop and prosper economically and politically as a “fortress state” while it remains at war.

A failure to recognize the current realities of the conflict carries grave risks for Ukraine’s future and for U.S. strategic interests.

Although a Ukrainian military victory is increasingly out of reach, the United States still has important advantages in the wider conflict over securing Ukraine’s independence and ensuring stability in Europe — issues that lie at the roots of the Russian invasion. Supplementing our military aid to Ukraine with vigorous diplomatic engagement with Russia would open up new possibilities and advantages for the West. We should test Putin’s repeated statements (for example in his recent interview with Tucker Carlson on February 8, 2024) that Russia wants to enter into negotiations, and that Moscow can recognize Ukrainian independence as long as Ukraine is not actively hostile to Russia.

This paper addresses why pro–Ukrainian actors must adapt their approach and how a new diplomatic strategy can protect the key interests of the United States and Ukraine. We examine the limits of what Russia can achieve despite its growing battlefield momentum, why Moscow still has some incentives to negotiate despite its distrust of American intentions, and what steps American officials could take to increase the likelihood of an acceptable end to the war.

The Military Balance: Time is Not on Ukraine’s Side

Going into 2023, the belief that Ukraine could reconquer all or most Russian-held territory was informed by Ukraine’s remarkable achievements in the months following the initial Russian invasion. The magnitude of Ukrainian success in defeating the Kremlin’s initial hopes of reducing Ukraine to a Russian client state was in fact even greater than generally perceived at the time. If the war were to end today, some 80 percent of Ukraine would be independent and at least informally aligned with the West. This would reverse more than 300 years of Russian domination of Ukraine.2

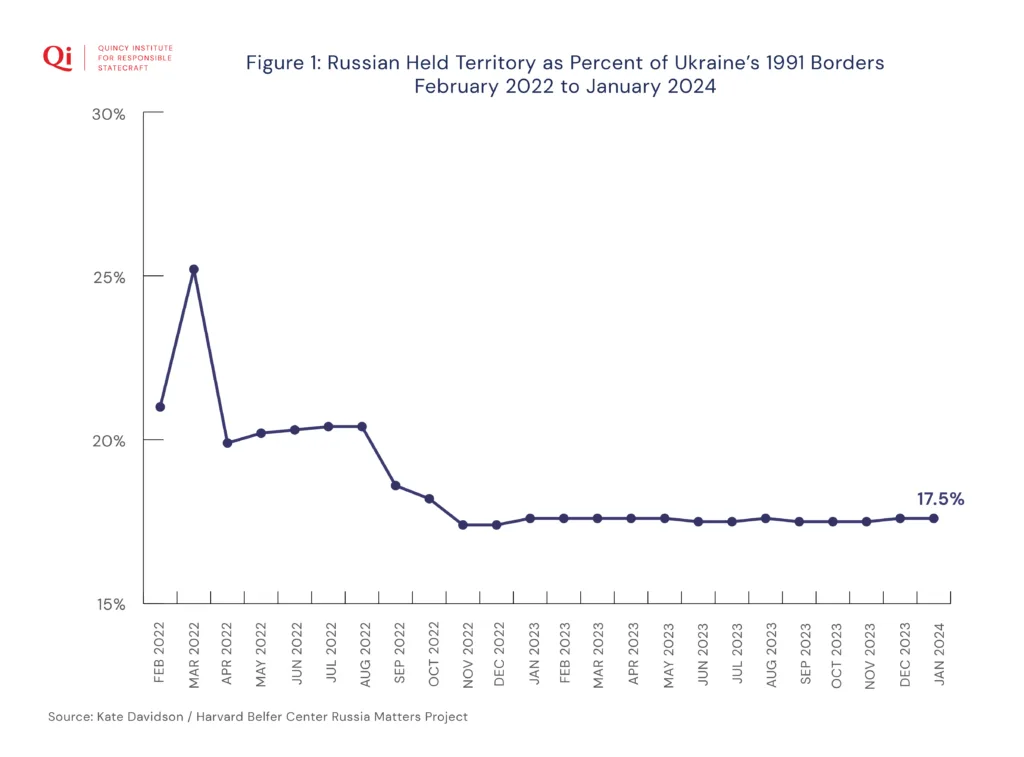

But in 2023 Ukrainian battlefield advances stalled. As Figure One shows, the front lines of the conflict barely moved during 2023 as the Ukrainian mid-year offensive failed. Ukrainian territory held by Russia is almost identical to what it was a year ago, at approximately 18 percent of Ukraine’s territory under 1991 borders.

Ukrainian victories in 2022 were due to multiple factors: appallingly bad Russian staff work, intelligence, tactics and logistical preparation; Russian troop numbers that were inadequate to the tasks set them; rapid Ukrainian mobilization coupled with a flood of enthusiastic volunteers; Western weapons that nullified Russia’s vast superiority in armor and aircraft; and U.S. intelligence that informed the Ukrainians of the precise location, time and numbers of planned Russian attacks.3

Of all these factors, only the last two still work in Ukraine’s favor, and only if Ukraine remains on the defensive. Other factors have shifted from the start of the war:

- Russian staff work and tactics have greatly improved as their military adapted.4

- Russia has more than doubled the size of its force on the ground as compared to 2022.

- Ukraine has taken substantial losses from among the troops initially mobilized.

- Many Russian weapons are more effective defending against attacking forces than they are on the offensive.

- Russia has greatly increased its capacity to jam the electronic systems on which much of the NATO–supplied weapons rely.

The Western powers hoped that by increasing their supply of weapons they could reinvigorate Ukraine’s offensive capacity in the face of these new factors. But in 2023 the large quantities of weapons the United States supplied for the Ukrainian counteroffensive did not help Ukraine even to break through the first line of Russian defenses. Furthermore, supplies of Western weaponry at this level are unlikely to continue. As Liana Fix and Michael Kimmage acknowledge,

A divided Congress likely has no “mountain of steel,” as U.S. officials have called the materiel they gave Ukraine in early 2023, to provide for a renewed counteroffensive in 2024, and European countries are falling short in the assistance they have promised. In purely military terms, Ukraine’s path to victory is unclear.5

Liana Fix and Michael Kimmage

It is all too clear that sufficient quantities of aid are not guaranteed even in the medium term, let alone indefinitely.6 The interest of Western publics in the conflict is declining.7 EU leaders have admitted in private that they cannot substitute for U.S. aid to Ukraine (especially in the military sphere) should that aid falter.8

In the United States, Ukraine has been trapped in Congressional gridlock despite warnings of imminent collapse of key military capabilities.9 Even if this gridlock is temporarily broken for a new aid package, current difficulties are a grim sign for the reliability of future assistance. Among Republicans in Congress, a large number share the views of Senator J.D. Vance:

[O]n the Ukraine question in particular, everybody with a brain in their head knows this was always going to end in negotiation. The idea that Ukraine was going to throw Russia back to the 1991 border was preposterous; nobody actually believed it…So what we’re saying to the president and really to the entire world is you need to articulate what the ambition is. What is $61 billion [in additional aid to Ukraine] going to accomplish that $100 billion hasn’t?10

Lauren Sforza

Thus, as the war enters its third year, the combination of Russian structural advantages over Ukraine in population and economic size and the political uncertainty of continued Western aid to Ukraine is forcing, as it should, a reconsideration of the insistence on rejecting negotiations with Russia and holding out for total reconquest of Ukraine’s 1991 borders. Western advocates of a continued reliance on a purely military strategy have fallen back on two claims. 11

The first proposes that certain tactical Ukrainian successes can bring strategic victory in the war. Thus some senior retired U.S. military officers have argued that Ukraine’ success with missile strikes against the Russian Black Sea Fleet at Sevastopol (which have apparently forced many of its warships to retreat to Novorossiysk) mean that Ukraine could drive Russian forces from Crimea — or force a broader Russian capitulation — by long–range bombardment alone. 12

Ukrainian success against the Black Sea Fleet is indeed significant, insofar as it reduces Russia’s ability to blockade Ukraine, as well Russia’s capacity for amphibious assault on Ukraine’s Black Sea coast.13 However, when it comes to Ukraine actually retaking Crimea or forcing a broader Russian capitulation, even if Kyiv were given the vastly greater amounts of Western weaponry and munitions necessary to attempt this, the Ukrainian army and navy would still have to carry out a major amphibious landing. This is perhaps the most challenging of all military operations, and one the Ukrainian military is ill equipped for.

Moreover, long–range air strikes have rarely had decisive strategic effects in war absent significant advances in capturing and holding territory. Equipping Ukraine for such a campaign would risk provoking large–scale Russian retaliation, as it would almost certainly fuel existing criticism from right–wing Russian nationalists that Putin has been too passive in defending Russian red lines.14

The second approach is to recommend that the United States and NATO accept the need for a “long war,” as NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg has said.15 Particularly fervent advocates of a military solution call for Western countries to further militarize their economies in order to sustain massive support for Ukraine indefinitely. 16

It is indeed true that given time, money and political will, the United States and NATO could give Ukraine much larger amounts of weaponry and ammunition. Steps in this direction are being taken. For example, the Pentagon has awarded $1.5 billion in contracts to increase production of 155 mm artillery shells, and has more than doubled monthly shell production since the beginning of the Ukraine war.17 However, it has also said that it needs an additional $3 billion in order to achieve the target of 100,000 shells a month by 2025 — a level that still falls well short of Russian production. 18

Moreover, while the West can provide Ukraine with weapons, it cannot provide the men to use them. Even as Russia’s forces in Ukraine increase, the Ukrainian military is experiencing difficulty maintaining an adequate number of high–quality troops.

According to Time Magazine, the average age of Ukrainian soldiers is now 43 years and rising fast — which is much too old for real combat effectiveness.19 Ukraine is facing greater and greater difficulties in recruiting conscripts, with many young men now evading service within Ukraine, bribing the authorities to exempt them, or fleeing abroad. Ukrainian government attempts to toughen and extend conscription laws are meeting strong resistance in society and in the Ukrainian parliament.20 Indeed, the need for large numbers of additional troops despite the political resistance to major increases in conscription appears to be an issue at the heart of President Zelensky’s conflict with General Zaluzhny, the recently dismissed former commander of Ukraine’s armed forces.21

Even if conscription was increased, all too many of the highly–motivated young men who joined up at the start of the war are now dead or disabled, and the quality of those remaining is much less certain.22

In contrast, Russian troop strength within Ukraine is increasing. As Figure Two shows, the number of Russian troops within Ukrainian territory is now well over double the size of the initial 2022 invasion force.

Further, the increasing Russian population advantage over Ukraine is likely to permit Russia to maintain or increase its growth in forces, and possibly overwhelm Ukrainian manpower resources. Although getting reliable data out of wartime Ukraine is a challenge, migration into the EU and into Russia in response to the war appears to have driven substantial Ukrainian population declines since the invasion. As Figure Three below shows, estimates of the population in Ukrainian–controlled territory today run from about one quarter at the high end to less than one fifth of Russia’s population.

While there are doubts about the quality of Russian troops, the sheer size of Russian military resources constitutes a structural advantage. As long as the Russians maintain substantial superiority in numbers, this gives them some chance of an overall strategic breakthrough, as opposed to limited tactical advances.23

Russia only has to fortify its existing battle line within Ukraine to hold the territory it has won. Beyond holding this territory, Russia has the potential to resume the invasion of northern Ukraine that it launched (with some initial success) at the very start of the war. Even if Belarus is excluded as a potential launch pad for a Russian offensive, that still leaves Ukraine with an additional possible frontline of some 600 miles to defend. The Ukrainian army has been doing its best to fortify the northern border; but where will it find the troops?24

Hopes that the Russian economy would collapse under sanctions and make continuation of the Russian war effort impossible have also not been realized. Russia has also been able to raise its spending on the military to six percent of GDP, and more than 60 percent of the state budget, while also achieving growth in GDP of 2.2 percent in 2023. Due to the willingness of most of the world to go on buying Russian energy and the collapse of imports from the West, Russia’s current account surplus grew to $16.6 billion in the third quarter of 2023.25

As a result, there is now little realistic prospect of further Ukrainian territorial gains on the battlefield, and there is a significant risk that Ukraine might exhaust its manpower and munitions and lay itself open to a devastating Russian counterattack. Recognizing this, and belatedly accepting the advice of Ukraine’s military chiefs, President Volodymyr Zelensky has now given the order that the Ukrainian army should stand on the defensive and fortify its existing lines.26

There is now little realistic prospect of further Ukrainian territorial gains on the battlefield.

As reflected in the shift to the defensive, knowledgeable insiders are admitting the core military weaknesses of the Ukrainian position. For example, General Zaluzhny, Ukraine’s former military commander during the first two years of the war, wrote a recent CNN article which highlighted the same structural issues facing Ukraine that we have described above as regards deficiencies in manpower, uncertain allied assistance, and Russian economic resilience under sanctions.27

Although the battle lines have not shifted substantially over the past year, the war in Ukraine is not likely to remain a stalemate. A lesson of World War One is that stalemates, however prolonged and bloody, do eventually end. In the words of Jack Watling regarding the Ukraine conflict:

When you look at the rates of attrition on both sides and what is being lost and consumed, it’s a position that can’t be maintained indefinitely. Stalemate would suggest that if we just left things as they were, it would remain the same. That’s not the case. It will remain the same for a period, and then you see non-linear progression as one side gains advantage or loses it.”28

This can be partly because of a change in tactics, but above all because in a war of attrition, the numbers, munitions and economy of one side falter before the other does so, leading to a collapse either of the army or the home front. As things stand at present, if either side in the Ukraine War eventually cracks, it seems likely to be Ukraine.

Can Ukraine Thrive While War Continues?

Proponents of sustaining a “long war” between Ukraine and Russia appear to assume not only that Ukraine can sustain its fight on the battlefield but that it can survive and even thrive as a society while it remains at war. Many advocates of a “long war” approach optimistically portray a “Fortress Ukraine” able to develop beyond the poverty and corruption that has long plagued the country, as well as join the European Union to share in broader European prosperity, all while Russian missiles rain down and bitter battles rage along the eastern border.

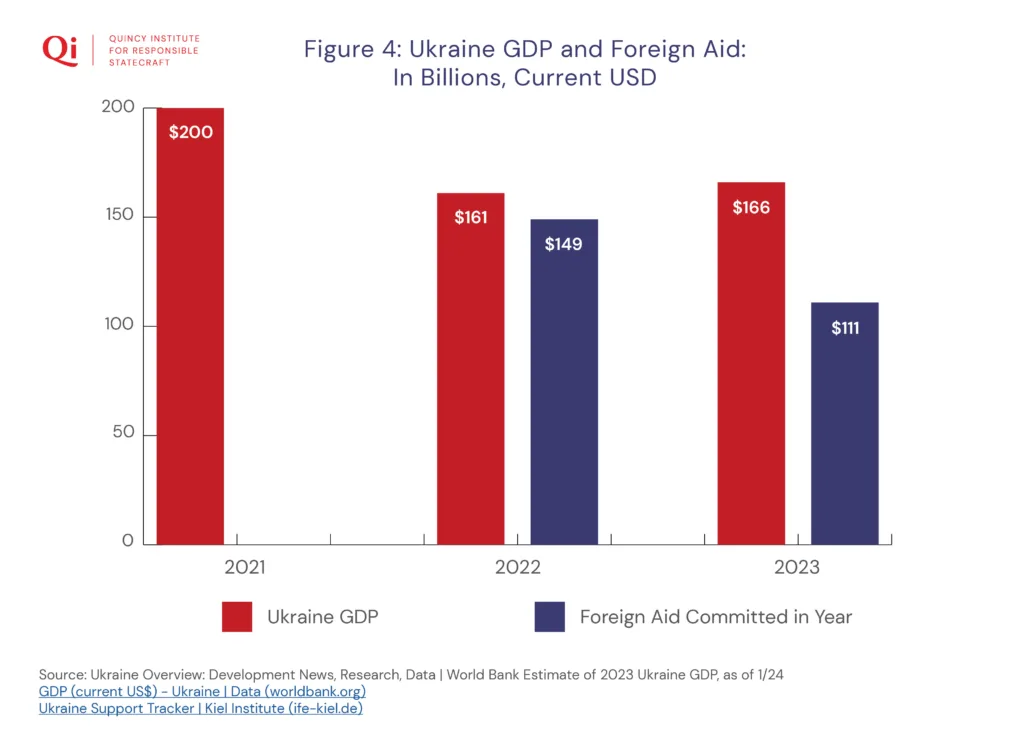

Unfortunately, this optimistic vision is at odds with several aspects of Ukraine’s reality. Ukraine is overwhelmingly dependent on Western military and economic aid if it is to survive — and it has become obvious that the continuation of this aid cannot be guaranteed.29 Figure Four below compares Ukraine’s GDP to flows of foreign aid from 2021–23. It is immediately evident that during wartime Ukraine’s military and civilian economy has been profoundly dependent on a sustained and massive flow of foreign assistance. For example, Ukraine’s predicted budget deficit of $43 billion in 2024 (more than a quarter of total GDP) will have to be entirely covered by Western aid.30

However, the practical and political sustainability of this assistance is now in doubt. New commitments of aid to Ukraine dropped to almost zero in the last four months of 2023. While the EU has recently made a new commitment to a $54 billion four–year aid package, large additional amounts will still be needed to sustain the pace of assistance for 2024 and future years.31 At the time of writing, it remains highly unclear just how much more will in fact be forthcoming.32

Western leaders continue to declare that their countries will continue to support Ukraine “for as long as it takes” — though “as long as it takes” to do what exactly they do not say, and indeed do not appear to know.33 Most have acknowledged that the war will end in negotiations, but they have also not distanced themselves from the Ukrainian “peace formula” of complete Russian withdrawal and war crimes trials, which in effect makes negotiations with Russia impossible, and implies a total Russian defeat that is becoming less and less credible.

These Western promises of support are pointless if the Ukrainians do not believe them, and dangerous if Ukraine does rely on them to seek complete victory in the war. In the view of Gwendolyn Sasse:

The mantra of ‘supporting Ukraine for as long as it takes’…increasingly resembles self-reassurance rather than a future-oriented strategy. Moreover, frequent references to ‘Ukraine’s victory’ have turned this phrase into a means for politicians to position themselves rather than act.34

Sam Meredith

It is clear that sufficient quantities of aid are not in fact guaranteed even in the medium term, let alone indefinitely.35 The interest of Western publics in the conflict is declining.36 EU leaders have admitted in private that they cannot substitute for U.S. aid to Ukraine (especially in the military sphere) should that aid falter, while congressional gridlock threatens Ukraine aid currently and seems likely to be an ever increasing factor if the war continues with no end in sight.37

Moreover, if the West is to accept a long war aimed at the complete defeat of Russia, then the present debate will have to take place again next year, and the year after that, and the year after that. Given how difficult this issue has proved recently, can anyone honestly and realistically promise that Western political systems will go on and on producing that aid, every year, indefinitely?

Even in the face of declining prospects for aid, some believe that Ukraine’s long term future can be sustained if it wins EU membership and fully enters the Western economic, social and cultural sphere. During the cold war, Western Europe was able to develop (or rather re–develop, after the destruction of World War Two) as the second great center of the world capitalist economy after the United States. This in turn fostered stable and successful liberal democracy. The extension of prosperity and democracy beyond Western Europe — first to the Mediterranean countries, then to the former communist states of eastern Europe — was assisted, in a series of stages, by the establishment, strengthening and expansion of the European Union.

But as long as the war continues it seems highly unlikely that such a prospect beckons for Ukraine. It is true that the EU has now agreed to accession talks with Ukraine and declared its openness in principle to Ukrainian membership.38 However, the EU’s assessment of requirements for membership shows that Ukraine still falls well short of EU standards in areas ranging from the control of corruption to democratic institutions to public financing and economic stability to minority rights.39 Addressing these shortfalls will be extraordinarily challenging while Ukraine remains in a state of war. Indeed, there are few if any precedents for nations joining the EU while in a state of conflict.40

Ukraine’s poverty is also a barrier to accession. Figure Five compares Ukrainian GDP per capita to both the EU average and the poorest EU member (Bulgaria), in constant international dollars adjusted for purchasing power parity. As the chart shows, even before the war Ukrainian economic production was continuously far below the EU average and well under half of that of the EU’s poorest member. The war has only expanded this gap, despite a flood of foreign economic and military aid.

Moreover, the Ukrainian state has been traditionally plagued by very high levels of corruption.41 In 2021, Transparency International’s corruption index ranked Ukraine at 122 out of 180 countries, below Egypt and South Africa. Recent confidential U.S. government documents that were leaked to the press show that the corruption issue is ongoing and concern about corruption remains high among Ukraine’s allies today.42

The Ukrainian political system is also showing disturbing signs of stress. Politically, war has led to a considerable degree of authoritarianism, with the banning of political parties, newspapers and TV stations and the imprisonment or exile of opposition figures, including some who cannot seriously be accused of sympathy for Russia. Culturally, it has led to a tremendous intensification of ethnic nationalism. This is understandable given the Russian invasion and the suffering it has caused; but it is nonetheless incompatible with core EU principles.43

Some of these obstacles could perhaps be ignored by a completely and unanimously sympathetic EU. However, opinion polls in key nations already show somewhat shaky support.44 And recent tension between Ukraine and even highly sympathetic nations like Poland over the economic issues involved with assistance to Ukraine demonstrate that when concrete economic challenges arise, support can quickly evaporate.45

Could Ukraine become a successful “fortress state” while still at war, even if it experienced substantial delays or difficulties in joining the EU? This too seems highly doubtful. Without a peace agreement, Moscow would have every incentive to “wreck” Ukraine and block any Ukrainian effort to transform itself into a fortress state partnered with the United States or NATO.

After one year of war, the World Bank estimated that over $400 billion would be needed for Ukraine’s economic reconstruction, not including the military costs of pursuing a continuing war.46 The figure would no doubt be even higher today. But Russia effectively wields a veto over that reconstruction. This massive scale of investment is highly unlikely to be sustainable while donors know that Russian strikes could destroy any new project at any given time. Building any effective nationwide air defense system to protect reconstruction projects would take many years and many billions in Western aid, and Russia’s growing pace of missile production suggests Moscow could sustain its ability to strike Ukrainian infrastructure for years to come.

Ukraine also faces formidable demographic obstacles to succeeding as a “fortress state.” Ukraine’s demographic outlook was discouraging even before the Russian invasion, as its pre–independence 1991 population of some 52 million declined steadily to 44 million in 2020, due to declines in life expectancy and birth rates as well as economic migration to Europe. The outbreak of war has further reduced the population actually living in Ukrainian–controlled territory to crisis levels. The loss of Crimea in 2014 removed a further 2.5 million inhabitants, and at least six million refugees — mostly well–off and well–educated, including a disproportionate number of women and children — have fled the country for Europe since that time. In addition, Russia claims that some seven million Ukrainians have fled to Russia since fighting began in 2014.

Although getting reliable data out of wartime Ukraine is a challenge, prominent Ukrainian demographer Elena Libanova now estimates that there are only 28 million persons under Ukrainian control — a drop of almost 40 percent since 2020.47 (See Figure Three above). She also estimates that Ukraine’s birthrate has dropped to 0.7 births per woman, among the lowest in the world. Both a strong military and a thriving economy demand a young, healthy, and productive labor force. But that slice of Ukraine’s population has been particularly hurt by the war, and so long as the war continues, refugees are unlikely to return to Ukraine in large numbers.

A frequent trope among those who believe that prosperity can be combined with ongoing conflict is to use the example of Israel.48 But the Israel model for Ukraine can be dismissed by one simple proposition: if Syria were Russia, Israel would not be Israel. In other words, if Israel had faced the permanent hostility of a neighbor with over 10 times its economy, higher technological capacity, and nuclear weapons, it would never have been able to develop as it has done.49

Prospects for Ukraine’s growth and development as an independent and prosperous democracy without a cessation of hostilities with Russia appear grim.

Ukraine would also require far higher levels of U.S. aid to sustain it than Israel ever has. In the 75 years since becoming a state in 1948 until the current Gaza War, Israel received more than $260 billion (in 2023 dollars) in U.S. aid. But to sustain Ukraine at war, the United States and the EU have had to give the same amount during just the first two years of the conflict (see Figure Four above). As argued here, to suggest that such massive Western aid can in fact be permanently guaranteed is a self–deception.

In sum, prospects for Ukraine’s growth and development as an independent and prosperous democracy without a cessation of hostilities with Russia appear grim, indeed.

The Promise of Diplomacy

Given the risks on the battlefield and the unlikelihood of establishing a thriving democratic state in Ukraine while it remains under active Russian attack, Washington would appear to have few good options for bringing the war to an acceptable end while ensuring Ukrainian security.

Nonetheless, there is much wisdom in the old adage that when a problem appears insoluble, expand it. That does not mean expanding the war itself to include other states: a Ukrainian victory on the battlefield is almost certainly out of reach even with Western intervention, and bringing U.S. or NATO forces directly into the fighting could easily escalate into nuclear use and mutual catastrophe. It does mean going on the diplomatic offensive, however, exploiting the advantages that the West still retains in the greater geopolitical game over Europe’s security architecture and Ukraine’s role within it.

Many reject this possibility out of hand.50 Among the claims made are that Russia is not motivated or willing to negotiate, that Putin would never accept an independent Ukraine, that any Russian success in the war would encourage aggression elsewhere, and that Moscow would not abide by the terms of any acceptable settlement.51

Some of these claims are dubious, some are exaggerated, and others are testable — and can only be tested through negotiations. It is certainly true that any negotiations with the Russians would be quite difficult. But those who reject diplomacy as a viable option underestimate the gap between what Russia can achieve through its own military efforts in Ukraine and what it needs to ensure its broader security and economic prosperity over the longer term. They also underestimate the ways in which verifiable agreements could be constructed even in areas where trust has been undermined by Russian aggression and years of bitter warfare.

Given the grim alternatives to a negotiated settlement, it is incumbent on U.S. policymakers to seriously explore the possibilities. Below, we analyze Russia’s incentives for negotiation in light of its own declared goals in the invasion of Ukraine, potential mechanisms to bring Russia to the table, and how the requirements for a sustainable agreement that both guarantees Ukraine’s security and offers Moscow sufficient incentives for compromise might be fulfilled.

Why would Russia negotiate?

If Ukraine cannot realistically mount an offensive able to recover Russian–occupied territories on the battlefield nor turn itself effectively into a fortress state able to hold off Russian advances for years to come, an inevitable question arises: Is a negotiating strategy aimed at forging an acceptable settlement with Russia a viable option? In other words, does Russia have any incentives to compromise in a war of attrition that increasingly is going Moscow’s way?

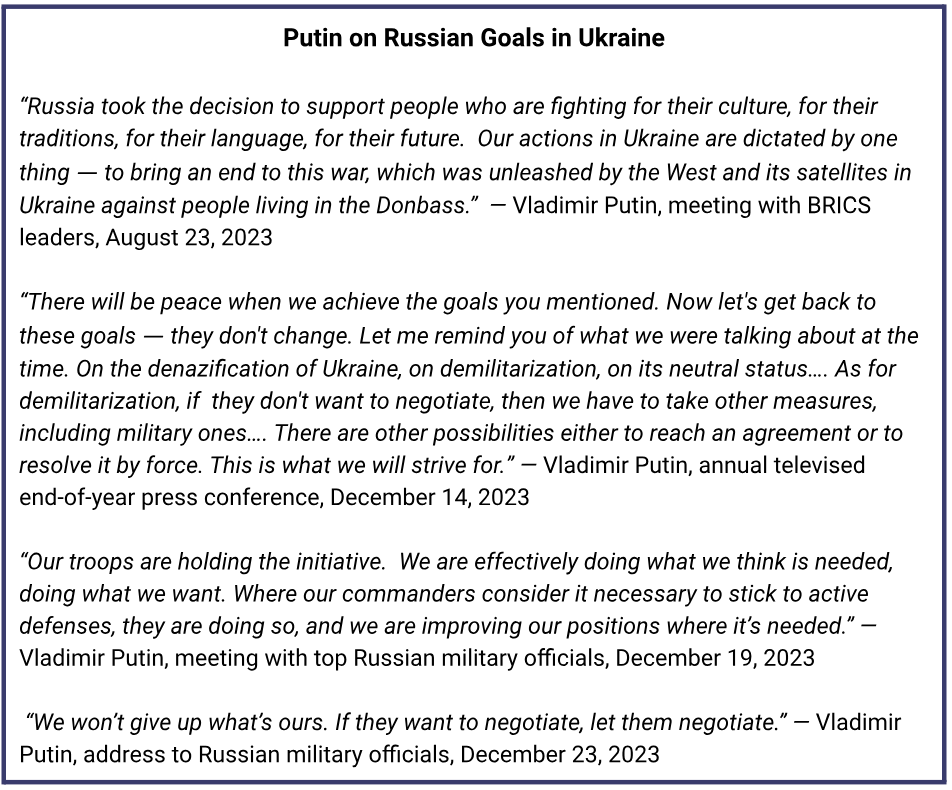

The answer to this question pivots on an assessment of Russia’s key aims in the war. Public statements by Putin (including his recent interview with Tucker Carlson), and other key Russian officials, as well as Russian conduct over the past three decades, suggests the following list of objectives.

- “De-NATOization.” Prevent Ukraine’s membership in NATO or de facto military partnership with the United States, potentially through a treaty of neutrality

- “Demilitarization.” Prevent post-war Ukraine from posing a military threat to Russia, including to Russian-held territory inside Ukraine’s 1991 borders.

- “De-Nazification.” Transform Ukraine into a friendly vassal state, or at a minimum prevent it from becoming an anti–Russian, ethno–nationalist state.

- Regather lands in eastern Ukraine that Moscow regards as rightfully Russian both historically and culturally.

- Accelerate the transformation of both the European security order and the broader international order from unipolar American primacy into a multipolar system in which Russia plays a meaningful role.

- Achieve these goals while avoiding direct war with the United States and NATO.

Russia’s progress in the war to date suggests that it has the ability to achieve some — but far from all — of these goals on the battlefield. These include blocking a Ukrainian military alliance with the West and recovering at least some of the territories in eastern Ukraine that it regards as historically and culturally Russian.

Despite the fact that Russia’s initial military thrust at Kyiv in 2022 was aimed at replacing the government of Ukraine with a pliable pro–Russia leadership, it is also clear that the Russian military is incapable of conquering — let alone governing — the vast bulk of Ukrainian territory by force.52 Conquest of all of Ukraine would require building and equipping a military force on a scale many multiples that of Russia’s current occupying forces, and far larger than the initial invasion force. Given the intense hostility to Russia in Ukraine, which has been cemented by years of war, conquest would also require devoting many years if not decades to an expensive occupation of decidedly hostile territory. 53

But as Ukraine’s supplies of men, artillery shells, and air defense munitions dwindle, Russia appears increasingly capable of capturing land in Ukraine’s east and south that it has officially annexed but does not yet occupy.54 And although Moscow cannot compel Washington or Kyiv formally to renounce their goal of Ukrainian membership in NATO, it can exercise an effective veto over Ukraine’s membership by refusing to end the war absent a binding Western pledge to deny Ukrainian admission to the alliance.

Demilitarization is a goal that Russia can achieve only to a limited degree through military efforts alone. One of the reasons Putin and the Russian military command settled on an attrition strategy following the failure of their initial bid to capture Kyiv was the difficulty in fighting a war of maneuver in the face of Western high–technology weaponry and advanced intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance. But another was that a slow war of attrition served the broader Russian objectives of not only winning the war, but also damaging Ukraine’s ability to reconstitute a post–war military.

As Washington has grown more pessimistic about Ukraine’s ability to drive Russian forces off of all occupied land, it has focused increasingly on building Ukraine into a fortress state capable of denying a Russian victory for many years to come.55 As Russian analyst Andrey Sushentsov has argued, the main goal of the United States has shifted toward the “preservation of the existing front line and stabilization of the situation: Ukraine will retain its mobilization potential and industry and will also be ready to continue to fight Russia.” 56

But it is in Russia’s interests, he says, to oppose this Western ambition and “for Ukraine to transform not into a well–armed ‘Israel,’ but into a sort of ‘Bosnia’ — a divided country, devoid of industrial potential and unable to become a significant counterweight to Russia.” Russia can certainly advance that objective on the battlefield. The longer the war continues, the greater the toll it is taking on Ukraine’s population, industry, and infrastructure. Ukraine is already struggling to muster the manpower needed to man an army; operate and maintain its equipment; and work in the factories needed to support it.57 Russian barrages of artillery, rockets, drones, bombs, and missiles can ensure that those challenges continue, if not grow, over time, particularly as Western supplies of air defense missiles diminish.58

Still, demilitarization through military efforts alone is a more expensive and more uncertain path to neutering Ukraine’s military potential than reaching a deal with Ukraine and the West on arms control measures would be, at least in principle. Russia could potentially occupy lands it has annexed but does not yet militarily control, but even after success in seizing them, Russia would be left with the problem of securing them against future attacks and reconstructing them in the face of probable sabotage attempts by Ukraine and sanctions from the West. Putin has appeared to recognize this problem by calling for the establishment of a “demilitarized zone” — an implicit contrast to the broader goal of a fully demilitarized Ukraine — that would keep Ukrainian artillery and missile forces at a safe distance from Russia and Russian–held territory.59

Just like the Soviet desire for Western recognition of post–World War Two borders in Eastern Europe drove Moscow’s positions during Helsinki negotiations in the 1970s, the Kremlin therefore has reasons to want at least de facto Western acquiescence to Russian control of Crimea and the Donbass. The alternative will mean a much higher level of Russian expense in fortifying those regions, and a much lower level of success in reconstructing them.

Moreover, although Russia can erode Ukraine’s military manpower and cripple its infrastructure, it cannot prevent the West from supplying Ukraine with some form of long–range strike capability absent an agreement with Washington and NATO. Ukraine’s military potential is only one aspect of a broader security problem for Russia — its vulnerability to strikes from NATO territory — that the war in Ukraine has exacerbated. This vulnerability will remain a significant danger absent arms control and confidence–and security–building measures (CSBMs) similar to those that helped keep the Cold War cold.

The war has in fact greatly damaged Russia’s ability to pursue peaceful security–building measures or play any meaningful role inside a new European security order.60 Instead, it has set Europe on a course toward long–term division and confrontation between Russia and NATO, while making diplomatic discussions about managing the dangers of such confrontation nearly impossible. Russia, in other words, has shown that it can block the further expansion of NATO into ex–Soviet republics, but it cannot fight its way into Western recognition that Russia has a legitimate role to play in Europe’s security order, nor can it reduce the potential for direct war with NATO absent diplomatic engagement with the United States and Europe. In sum, although Russia can make progress on demilitarizing Ukraine, it still has some significant reasons to want an understanding with the West over Ukraine and the broader European security order.61 Absent such an understanding, Russia faces a significantly more dangerous and fraught future.

Although Russia can make progress on demilitarizing Ukraine, it still has some significant reasons to want an understanding with the West over Ukraine and the broader European security order.

Regarding “denazification,” which Russian officials have not clearly defined, Russia’s invasion has been enormously counterproductive, accelerating Ukraine’s transformation into an anti–Russian, ethno-nationalist state that is likely to remain hostile toward Moscow for at least a generation to come, regardless of how the war unfolds from this point.62 But Russian ambiguity about this objective provides it with some degree of flexibility in claiming it has been achieved. It is certainly possible, for example, that growing unhappiness over the war could result in Zelensky’s removal from office, either electorally or otherwise, which the Kremlin could portray as fulfillment of its demand for “de–Nazification.” Indeed, signs of friction between Zelensky and other Ukrainian elites have grown clear.63 But it is also possible that a successor leadership could be equally or more anti–Russian than the Zelensky government has been.

Russia’s best hopes for a less ethno–nationalist and anti–Russian leadership in Ukraine would lie in two scenarios. In the first, the start of a formal EU accession process would incentivize Ukraine to rein in ethno–national extremists as it attempts to align with EU membership requirements. In the second, Ukraine would follow a path similar to Georgia after the 2008 war with Russia, with pragmatic leaders gradually coming to power who recognize that deepening commercial relations with Russia — while also seeking robust trade to Europe — is a path toward securing both their own fortunes and greater national prosperity.64 Nonetheless, both scenarios (which are not mutually exclusive) would be almost unimaginable absent an agreement among Ukraine, Russia, and the West to end the war.

Apart from specific war aims, Russia has other reasons to want a bargain with the West. The degree to which Russia is barred from meaningful discourse with the United States and Europe deepens its dependence on China and circumscribes the role it can play in a multipolar world order.65 So long as Western sanctions remain in place, Russia will have little to no commercial involvement in European markets and no seat in European councils overseeing security matters, nor will individual Russians enjoy the benefits of travel to European destinations. For a state that has for centuries looked to the West culturally and bridged East and West politically, Russia’s presently narrow geopolitical options must be to some degree discomfiting.

Getting Russia to the table

States typically seek negotiated ends to war when they doubt continued fighting will advance their goals and fear it might damage them. As they see the correlation of forces tilting toward Russia over time, Ukraine and the West are at the early stages of drawing such conclusions.66 By contrast, Russia has no compelling short–run need to compromise with Ukraine and the West anytime soon, as it has reasons at present to believe continued fighting will improve its position.67 However, as discussed above, Russia has long–term security interests that could be advanced more effectively through a negotiated settlement than by continual warfare and complete exclusion from the European security order. Under such circumstances, how might the United States draw Russia into a diplomatic process that preserves Ukraine’s independence, provides it with acceptable security, and mitigates the dangers of confrontation between Russia and the West in Europe?

The obstacles to such an endeavor are formidable. Levels of trust between Russia and the West are at rock bottom. Years of bloodshed have stoked intense mutual hatred between many Ukrainians and Russians, and Vladimir Putin has become politically radioactive in both the United States and Europe. Powerful political voices in Russia, Ukraine, and the West denounce calls for diplomacy and press those in power to double down on demonstrations of military strength.68 Meanwhile, the window for mutual compromise is narrowing, as the possibility that Ukraine might collapse under Russia’s military and economic pressure grows and the danger the United States will prove politically incapable of sustaining high levels of assistance mounts.

The first (though not necessarily the biggest) challenge will be to bring Russia to the negotiating table. A key prerequisite for negotiations will be continued Western assistance to Ukraine, without which Ukraine might collapse and Russia’s incentives to compromise would diminish. However, such assistance should be designed to create incentives for negotiation, rather than aimed at driving Russian forces off Ukrainian territory, which as discussed earlier in this paper is now all but impossible. Assistance which sustains Ukraine’s ability to defend itself by blocking or impeding Russian advances and to contend with Russia airstrikes will be critical to persuading Moscow that compromise would be a less costly and more effective path to achieving its goals than continued fighting.

A key prerequisite for negotiations will be continued Western assistance to Ukraine, without which Ukraine might collapse and Russia’s incentives to compromise would diminish.

A second prerequisite will be re–invigorating direct communication between Washington and Moscow. Neither state’s ambassador has been withdrawn, but neither has significant interaction with the host government; one of the ways Washington can signal its interest in diplomatic engagement with Russia is to reach out to Russia’s ambassador to talk while indicating that we are prepared to discuss the full range of issues in our bilateral relationship in the context of progress toward a settlement in Ukraine. Washington should supplement this step by seeking a strictly confidential channel of discussions between envoys with the respective trust of the White House and Kremlin. Such a “back channel” was critical to the successful resolution of the Cuban missile crisis, and it would help assure Russian skeptics that Washington is serious about finding terms of a settlement that would be acceptable to Ukraine, the United States, and Moscow.

Such steps might begin to address Moscow’s not altogether unreasonable concern that Ukraine and the West might intend to use negotiations merely to buy time for rearmament and enable a future Ukrainian offensive in the war — a fear that is parallel to the same concern about Russia expressed by Western critics of diplomacy.69 Francois Hollande’s and Angela Merkel’s admission last year that the French–German sponsorship of the “Minsk 2” plan for settling the war in the Donbass in 2015 was in fact a cover for Ukraine to build its military capabilities has attracted considerable attention in Russia, deepening doubts that the West would bargain in good faith.70 The combination of such distrust with Moscow’s likely belief that it can advance many of its war aims unilaterally means that Russia is unlikely to agree to a mutual ceasefire as a first step toward a settlement. To underscore its seriousness about diplomacy, Washington will likely have to indicate that it is prepared to discuss the issue of NATO membership for Ukraine in the context of a broader agreement on ending the war and managing broader threats to European security.

Indicating to Moscow that we might consider accepting Ukraine’s military neutrality would go some distance toward convincing the Kremlin that we intend to do more than play for time in negotiations. It would also signal that we recognize the war is about more than territory and other bilateral disputes between Russia and Ukraine and includes broader issues about Europe’s security architecture that cannot be addressed absent direct U.S. involvement.

Given Putin’s other war objectives, however, it cannot be guaranteed that this move alone would bring the Russians to the table. To do that, we will probably need to enlist the help of two sets of players on whom Moscow is increasingly dependent: the Global South and China. Neither of these actors could or would attempt to coerce Russia into ending the war by aligning with efforts, such as the proposed Ukrainian “peace formula,” which are effectively ultimatums that do not allow for any accommodation of Russian negotiating positions.71 Indeed, they have mixed feelings about the Russian invasion: few want to see either a clear Russian defeat or Western triumph in the war, having sympathy both for Ukraine’s plight and for the Kremlin’s complaints about American stewardship of the world order.

Both players, however, could help bring pressure on Russia to demonstrate that it is willing to seek a reasonable settlement in Ukraine. Key players in the Global South, including Brazil and South Africa, have launched tentative efforts to promote negotiations.72 These players could provide the United States with a means of escaping from the diplomatic cul-de-sac that its categorical opposition to compromise with Russia over the European security order has created. In meetings with various Global South diplomats urging a settlement of the war, Putin has repeatedly insisted that Russia is open to negotiations and blamed Ukraine and the West for refusing talks. Ukraine’s formal ban on negotiations with Russia, coupled with the Biden administration’s slogan that it will discuss “nothing about Ukraine without Ukraine,” has enabled such rhetoric.73 Should Washington endorse calls from the Global South for talks, it would in effect call Russia’s bluff, pressing Putin to demonstrate his alleged openness.

It might also ease an acute political problem in Ukraine. Were Zelensky independently to call for negotiations, he would open himself to potentially destabilizing attacks from Ukraine’s political right wing, which strongly opposed his efforts early after his election in 2019 to find a compromise with Russia and end the war in the Donbass. It is highly improbable that Zelensky or any Ukrainian president could survive initiating talks with Russia absent public pressure from Washington on which to pin blame.

Deepened American engagement with China over settling the war in Ukraine could also constrict Putin’s room for diplomatic maneuver over the war. Beijing has already called for a settlement and appointed a special peace envoy.74 While China is no doubt pleased that assistance to Ukraine has drained American stockpiles of weapons that might otherwise be available for defense of Taiwan, continued fighting will only incentivize expanded military production in the United States and Europe. At this stage, Beijing is almost certainly concerned that perceptions of its sympathy for Russia in the war could jeopardize its economic relations with Europe and prompt greater European involvement in Asian security affairs.75 Beijing’s admonitions to Russia about nuclear use over Ukraine also suggest that it worries about prospects for escalation into direct clashes between Russia and the West, with potentially severe consequences for China.

Thus, while it is true that its broader strategic partnership with Russia means that China is unlikely to press Russia for a unilateral ceasefire or withdrawal from Ukraine, it nonetheless has strong reasons to want a negotiated peace in the war that addresses key Russian security concerns while preserving Ukrainian independence and sovereignty.

Because Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has greatly increased its economic and geo–strategic dependence on Beijing, Moscow would be unlikely to object publicly to Chinese talks with the West over settling the war.76 Yet any prospect that China might do so would be concerning for the Kremlin, just as Ukraine has been wary of possible U.S.–Russian negotiations without Ukrainian participation. The combination of growing U.S. flexibility with deepening Chinese involvement might be sufficient to bring Putin to the negotiating table.

At the table

The question of who should sit at the negotiating table is critical. As noted earlier, any bilateral negotiation between Russia and Ukraine would almost certainly fail. Should Zelensky seek such talks on his own initiative, he would run a grave risk that domestic political opponents would push him from power. For its part, Russia is convinced that the United States, not Ukraine, is the key to any durable settlement. Ukrainian representatives are in no position to negotiate over the broader contours of Europe’s security architecture, which the Kremlin regards as the central issue of the war, and which pivots on the policies of the United States and its influence over NATO allies.

Similarly, any attempt to reach a U.S.–Russian bargain and impose it on Ukraine would also fail. Several issues in the war — such as territory and the treatment of ethnic and cultural Russians living in Ukraine — are bilateral matters between Moscow and Kyiv that do not involve the United States (though minority rights will be an issue for the EU in negotiations on Ukrainian membership). Just as Ukraine could not ensure American compliance with any deals it tried to forge with Moscow over broader European security matters, Washington could not guarantee Kyiv’s support for any bargain with Russia that it might attempt to strike over Ukrainian territory.

These realities suggest the need for a negotiating framework with variable geometry. Some aspects of the war will require direct Ukrainian–Russian negotiations, including on such matters as delineating and protecting borders (which will almost certainly take years if not decades to officially work out, and may — as in Cyprus — have to be shelved indefinitely). Others will require trilateral or multilateral discussions, such as negotiating limitations on Ukrainian military holdings, American and Western military involvement in Ukraine, and Russian military deployments in occupied Ukrainian territory and the adjacent region. Still other aspects, such as economic reconstruction and providing security assurances to Ukraine, will require broader international involvement.77

The organization of such talks could parallel the “baskets” approach taken by the Helsinki talks in the 1980s, with participation in each basket varying.78 A security basket would address arms control, confidence– and security–building measures (CSBMs), demining, and other military matters. An economic basket would handle such issues as economic reconstruction, sanctions relief, and war reparations. A human dimension basket could discuss prisoners of war, war crimes, ethnic minorities, and other related matters.

Contours of a compromise

To be effective and enduring, any settlement must address key concerns of Ukraine, Russia, and the West.

- For Ukraine, this means reliable assurances that it will not be vulnerable to another Russian invasion and has a viable path to reconstruction and economic prosperity.

- For Russia, this means reliable assurances that Ukraine will not be an ally of the United States or host NATO weapons or forces.

- For the United States and Europe, this means reliable assurances that Moscow will not parlay military success in Ukraine into broader threats to Russia’s neighbors or to NATO member states.

Given the difficulty of negotiations, it is impossible to predict in advance the details of a settlement. However, contrary to the claims of those who reject diplomacy, a settlement that addresses all of these concerns is possible in principle. In fact, Ukraine and Russia moved some distance toward such a compromise under Turkish and Israeli mediation in March and April 2022, when the two sides outlined a draft agreement that traded Ukrainian neutrality for multilateral security guarantees and began to zero in on limits for Ukrainian military holdings, prior to Ukraine’s renouncing negotiations with Russia and betting that it could drive back Russian forces from occupied territories.80

Given Russia’s growing military advantages since that time, Moscow would almost certainly drive a harder bargain today, particularly as it relates to caps on Ukrainian military holdings. But the fundamental bargain — Ukrainian neutrality and a multilateral arms control regime in return for Ukrainian independence and a path toward economic prosperity — remains the most promising means of addressing all sides’ key interests and incentivizing mutual compliance with terms of a settlement.

Although Ukraine’s position in the war is eroding over time, both Ukraine and the West still retain leverage in attempting to advance their interests.81 The threat of deeper American military involvement in Ukraine — either by intervening more directly in the fighting or by providing more advanced weapons to Kyiv — is something that Moscow clearly wants to preclude. Making clear to the Kremlin that Washington might have no alternative to such involvement absent a settlement would serve as a powerful incentive for Russian compromise. In parallel, the prospect of gradually easing Western sanctions in return for progress in forging and implementing a settlement would add a sweetener for a deal.

Both Ukraine and the West still retain leverage in attempting to advance their interests.

The biggest incentive for Russian compromise would be geopolitical: the prospect of gradually regaining a recognized diplomatic role in European security affairs that would reduce its dependence on China and provide greater geostrategic autonomy in dealing with both West and East.82 In this regard, provisions for securing Ukraine’s neutrality may offer a creative way to allow Russia to earn its way into the halls of European diplomacy. With U.S. and perhaps Chinese involvement, negotiators could build upon Ukraine’s 2022 proposal for establishing an international group of guarantors that would include the permanent members of the UN Security Council, as well as such states as Germany, Italy, Poland, and Turkey.83 These states could eventually expand their functional cooperation in securing and guaranteeing Ukraine’s neutrality into addressing broader issues in European security affairs and provide a path for translating Russian compliance with a Ukraine settlement into restoring Russia–West dialogue more generally.

Russia’s good faith implementation of a settlement in Ukraine could allow those guarantors to evolve over time into a formal body, smaller and more functional than the consensus–based, 57–member Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe. Europe has long lacked an operational forum similar to the Concert of Europe in which key powers could find pragmatic ways to balance competing interests and prevent brewing crises. The prospect of involvement in such a body could serve as a significant incentive for Moscow to strike a compromise over Ukraine’s independence and pursue a broader détente with the West.

Russia would certainly demand some form of cap or limitation on Ukraine’s military holdings and the weaponry stationed in the country. This aligns with Russia’s “demilitarization” goal in Ukraine and its perceived vital security interests. Such caps would require U.S. involvement as well.84 To preserve Ukraine’s security, any caps on Ukrainian military resources should be paired with complementary ceilings on Russian military forces that are geographically positioned to threaten Ukraine.

The goal should be to establish mutually applicable ceilings on both Russian and Ukrainian weapons inside defined geographic zones, coupled with transparency, notification, and inspection requirements. This could be modeled loosely on the approach taken in the now defunct Adapted CFE Treaty. Crucially, in this treaty Russia agreed to limitations on weaponry that Russia could station on its own territory in the North Caucasus and near Ukraine. Kyiv’s strongest leverage in such negotiations will be U.S. involvement and willingness to help rebuild and modernize Ukraine’s military — which would provide a strong backstop if Russia did not agree to verifiable limitations on its own forces.85 Further, as was demonstrated in the lead–up to the 2022 invasion, U.S. satellite technology and surveillance capability would provide powerful methods of rapidly verifying Russian compliance with an agreement around the positioning of its own military forces.86

The question of Ukraine’s territorial delineation is a particularly thorny problem, and one that is highly unlikely to be resolved through official compromise. It is also not an appropriate matter for non–Ukrainian countries to determine unilaterally. The failure of Ukraine’s counteroffensive in 2023 to break through Russian defenses and recapture Russian–occupied territory means that Ukraine will almost certainly not be capable of recovering all the land under its 1991 borders, and Russia will be loath to surrender at the negotiating table land that it regards as Russian for which it has sacrificed considerable blood and treasure.87 The best one might hope for would be to establish a settlement process in which agreeing on borders is not a prerequisite for ending the fighting, similar to the wars in Cyprus and the Korean peninsula. Ukraine’s 2022 proposal in fact envisioned such an approach, positing a 15–year consultation period on the status of Crimea that would come into force only after a complete ceasefire.88

Finally, there is the frequently expressed concern among some Western commenters that any negotiated peace would somehow embolden Russia to engage in further aggression toward neighboring countries.89 The chances that Russia might parlay some kind of victory in Ukraine into new invasions in Europe are in fact quite low. In Ukraine, Russia has had a formidable challenge conquering territory on its immediate border, on terrain it knows well, with the benefit of short supply lines and years of intelligence preparation. It is difficult to imagine that Russia could successfully invade a NATO state, for which NATO would very likely have advance intelligence warning and would almost certainly invoke an Article V defense. It would also involve much longer supply lines and much less favorable conditions. Nor are there any signs that Russians desire such a war. In fact, Russia has gone to great lengths to avoid direct clashes with NATO in its invasion of Ukraine.

Conclusion – U.S. Policy Steps

The discussion above gives a sense of specific policy steps the United States could take to pave the way toward the negotiating table. These steps include:

- Restoring defensive aid to Ukraine: It is important to lift the question of aid to Ukraine out of its current political morass and establish that the United States will aid Ukraine’s self-defense unless and until Russia comes to the negotiating table. However, aid should not be targeted at goals that are militarily impractical and signal hostility to any negotiated settlement, such as the complete defeat of Russia. The alignment of the intent, level, and type of aid with the goal of a negotiated solution should reduce political opposition to aid, which is currently driven in part by the fear of an endless war and unlimited costs.

- Open a confidential diplomatic back channel to Russia: Washington should seek mutually trusted envoys from the United States and Russian side who could begin private communication around the possibility of negotiations.

- Privately indicate that the United States is open to discussing NATO membership for Ukraine: As discussed above, this would be a powerful signal to Russia of Western seriousness in seeking peace. It would also carry little if any practical cost given that the reality of Western actions show that the United States and other NATO members do not wish to involve their own forces in a Ukraine conflict.

- Reach out to China and the Global South to discuss the parameters of a negotiated compromise in Ukraine: Such outreach would also be private, but could have a powerful effect in demonstrating our seriousness to Russia in seeking a settlement.

- Change U.S. public rhetoric: Our public rhetoric should indicate openness to negotiations rather than the belief that peace can be obtained purely by ultimatum or coercion, or that conflict should be sustained indefinitely.

Even if the United States embarks seriously on an effort to create a path to negotiations, the process of compromise will not be easy or simple. But the alternatives — for Ukraine and the world — will be far worse.

Program

Citations

Mick Ryan, “Russia’s Adaptation Advantage,” Foreign Affairs, February 5, 2024, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/ukraine/russias-adaptation-advantage ↩

Anatol Lieven, “The Perilous Pursuit of Complete Victory in Ukraine,” The American Prospect October 19, 2023, https://prospect.org/world/2023-10-19-perilous-pursuit-victory-ukraine/ ↩

Anatol Lieven, “Why the Russians are losing their military gambit in Ukraine,” Responsible Statecraft, March 28, 2022, https://responsiblestatecraft.org/2022/03/28/why-the-russians-are-losing-their-military-gambit-in-ukraine; Bradley Martin et al., “Russian Logistics and Sustainment Failures in the Ukraine Conflict,” RAND Corporation, January 1, 2023, https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA2033-1.html; Seth G. Jones, “Russia’s Ill-Fated Invasion of Ukraine: Lessons in Modern Warfare,” CSIS, June 1, 2022, https://www.csis.org/analysis/russias-ill-fated-invasion-ukraine-lessons-modern-warfare ↩

Mick Ryan, “Russia’s Adaptation Advantage,” Foreign Affairs, February 5, 2024, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/ukraine/russias-adaptation-advantage ↩

Liana Fix and Michael Kimmage, “A Containment Strategy For Ukraine,” Foreign Affairs, November 28, 2023, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/ukraine/containment-strategy-ukraine ↩

Henry Foy, James Politi and Ben Hall, “The West wavers on Ukraine,” Financial Times, December 8, 2023, https://www.ft.com/content/2447a4b4-bbff-4439-a96c-e3c5404ed105 ↩

Alexander Baunov, “The danger of losing focus on Russia’s war against Ukraine,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, January 17, 2024, https://carnegieendowment.org/politika/91398; Stephen Collinson, “Ukraine’s US lifeline is hanging by a thinning thread,” CNN, December 5, 2023, https://www.cnn.com/2023/12/05/politics/us-ukraine-aid-congress-analysis/index.html ↩

Sam Meredith, “EU leaders say they can’t fully replace US support to Ukraine as funding fears grow,” CNBC, October 5, 2023, https://www.cnbc.com/2023/10/05/russia-war-eu-says-europe-cannot-replace-us-support-to-ukraine.html ↩

Katie Bo Lillis, Natasha Bertrand, Haley Britzky and MJ Lee, “Grim realization sets in over state of Ukraine war as funding fight continues in Washington,” CNN, January 19, 2024, https://www.cnn.com/2024/01/19/politics/grim-realization-ukraine-washington-funding-fight/index.html ↩

Lauren Sforza, “Senate Republican says US needs to accept Ukraine will ‘cede some territory’ to Russia,” The Hill, December 10, 2023, https://thehill.com/homenews/senate/4352409-senate-republican-says-us-needs-to-accept-that-ukraine-will-cede-some-territory-to-russia/ ↩

Alexander J. Motyl and Dennis Soltys, “Stasis is not Stalemate in the Ukraine War,” The National Interest, November 29, 2023, https://nationalinterest.org/feature/stasis-not-stalemate-ukraine-war-207592; Timothy Snyder, “We must ditch the ‘stalemate’ metaphor in Ukraine’s war,” Financial Times, October 20, 2023, https://www.ft.com/content/5791ec24-3aa0-4a98-a89f-f955c3abcde5 ↩

David Brenan, “Ukraine ‘running rings around Russia’ amid Crimea wins: ex-General,” Newsweek, October 8, 2023, https://www.newsweek.com/ukraine-running-rings-around-russia-crimea-wins-black-sea-general-ben-hodges-sevastopol-1832739; Luke Coffey and Peter Rough, “The shortest path to victory in Ukraine goes through Crimea,” Foreign Affairs, December 8, 2023, https://foreignpolicy.com/2023/12/08/ukraine-russia-war-aid-congress-biden-victory-counteroffensive-crimea ↩

Basil Germond, “Ukraine war a stalemate on land but not at sea,” Asia Times, November 24, 2023, https://asiatimes.com/2023/11/ukraine-war-a-stalemate-on-land-but-not-at-sea/ ↩

Connor Echols, “Russian hawks push Putin to escalate as US crosses more ‘red-lines’,” Responsible Statecraft, September 12, 2023, https://responsiblestatecraft.org/atacms-ukraine-russia-putin/ ↩

Leonie Cater, “NATO chief warns Ukraine allies to prepare for a long war,” Politico, September 17, 2023, https://www.politico.eu/article/nato-chief-jens-stoltenberg-warns-ukraine-allies-to-prepare-for-long-war/ ↩

“Ukraine faces a long war: a change of course is needed,” The Economist, September 21, 2023, https://www.economist.com/leaders/2023/09/21/ukraine-faces-a-long-war-a-change-of-course-is-needed; Lawrence Freedman, “What should Ukraine do next?” Substack, November 29, 2023, https://samf.substack.com/p/what-should-ukraine-do-next ↩

Sam Skove, “In race to make artillery shells, US, EU see different results,” Defense One, November 27, 2023, https://www.defenseone.com/business/2023/11/race-make-artillery-shells-us-eu-see-different-results/392288/ ↩

Jen Judson, “US Army awards $1.5 billion to boost global production of artillery rounds,” Defense News October 6, 2023, https://www.defensenews.com/land/2023/10/06/us-army-awards-15b-to-boost-global-production-of-artillery-rounds/; Mike Stone, “US Army says it needs $3 billion for 155 mm artillery rounds,” Reuters, November 7, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/business/aerospace-defense/us-army-says-it-needs-3-billion-155-mm-artillery-rounds-production-2023-11-07 ↩

Simon Shuster, “Volodymyr Zelensky’s Struggle to Keep Ukraine in the Fight,” Time, November 1, 2023, https://time.com/6329188/ukraine-volodymyr-zelensky-interview/?utm_source=substack&utm_medium=email; Roman Olearchyk, “Manpower becomes Ukraine’s latest challenge as it digs in for a long war,” Financial Times, November 26, 2023, https://www.ft.com/content/25711074-5e1a-494a-9d7c-ccb535f671d5 ↩

Veronika Melkozerova, “Bloodied and exhausted: Ukraine’s effort to mobilize more troops hits trouble,” Politico, January 11, 2024, https://www.politico.eu/article/defense-ukraine-mobilization-bill-parliament-kyiv-balance-justice-security-war-economic-survival-russia-putin-zelenskyy/; Abdujalil Abdurasulov and Megan Fisher, “Ukraine MPs reject bid to crack down on draft dodgers,” BBC, January 11, 2024, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-67949900 ↩

John Hudson, “Ukraine informs U.S. about decision to fire top general,” Washington Post, February 2, 2024, https://www.washingtonpost.com/national-security/2024/02/02/zaluzhny-zelensky-white-house/ ↩

Olena Harmash and Tom Balmforth, “ ‘At what cost?’ Ukraine strains to bolster its army as war fatigue weighs,” Reuters, November 28, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/at-what-cost-ukraine-strains-bolster-its-army-war-fatigue-weighs-2023-11-28/ ↩

Stefan Wolf and Tatyana Malyarenko, “A Russian spring offensive would wrong foot Ukraine,” Asia Times, January 13, 2024, https://asiatimes.com/2024/01/a-russian-spring-offensive-would-wrongfoot-ukraine/ ↩

Olena Harmash, “Zelenskiy orders Ukraine to strengthen northern defenses,”Reuters, June 30, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/ukraines-zelenskiy-orders-moves-strengthen-northern-military-sector-2023-06-30/ ↩

Tom Wilson and Chris Cook, “The West’s russia oil ban, one year on,” Financial Times, December 10, 2023, https://www.ft.com/content/69d83a44-1feb-4d6b-865d-9fb827b85578; Henry Foy, “Can the EU uphold its promises to support Ukraine ‘as long as it takes’?” Financial Times, December 11, 2023, https://www.ft.com/content/d5035b51-1a15-4093-938f-55a5e98fd69d ↩

Marc Santora, “‘They Come in Waves’: Ukraine Goes on Defense Against a Relentless Foe,” The New York Times, February 4, 2024, https://www.nytimes.com/2024/02/04/world/europe/ukraine-defense-east.html; Nate Ostiller, “Ukrainian offensive ‘did not achieve desired results’, Zelensky says,” Kyiv Independent, December 1, 2023, https://kyivindependent.com/zelensky-war-has-entered-new-phase/ ↩

Valerii Zaluzhnyi, “Ukraine’s army chief: The design of war has changed,” CNN, February 1, 2024, https://www.cnn.com/2024/02/01/opinions/ukraine-army-chief-war-strategy-russia-valerii-zaluzhnyi/index.html ↩

Gideon Rachman, “Transcript: Is the balance tilting towards Russia in Ukraine?” Financial Times, November 16, 2023, https://www.ft.com/content/412c6c23-1bb4-42e0-a703-dfe7f0f5f10e ↩

David Lawder, “Yellen says US would be ‘responsible for Ukraine’s defeat’ if aid fails in Congress,” Reuters,December 5, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/world/us/yellen-says-us-would-be-responsible-ukraines-defeat-if-aid-fails-congress-2023-12-06 ↩

Olena Harmash, “Will Western aid plug Ukraine’s gaping budget deficit in 2023?” Reuters, December 5, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/will-western-aid-plug-ukraines-gaping-budget-deficit-2024-2023-12-05/ ↩

Matina Stevis-Gridneff and Monika Pronczuk, “The E.U.’s $54 Billion Deal to Fund Ukraine, Explained,” The New York Times, February 1, 2024, https://www.nytimes.com/2024/02/01/world/europe/eu-ukraine-hungary.html ↩

Daryna Krasnolutska, “New aid to Ukraine drops to lowest level since war began,” Bloomberg, December 7, 2023, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-12-07/new-aid-to-ukraine-drops-to-lowest-level-since-war-began ↩

Peter Caddle, “Win or lose, Brussels has fumbled the war in Ukraine,” Brussels Signal December 28, 2023 at https://brusselssignal.eu/2023/12/win-or-lose-brussels-has-fumbled-the-war-in-ukraine/; John Bacon, “‘We’re pretty much done’; Unwavering support for Ukraine begins to waver,” USA Today October 13 2023, at https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/world/ukraine/2023/10/03/ukraine-aid-support-russia-war/71032800007/ ↩

Gwendolyn Sasse, “Time is of the essence in defending Ukraine,” Financial Times December 20, 2023 at https://www.ft.com/content/36ba12ed-7a0f-4a3a-870e-b38363ad92d9. For an example of such promises, see Ursula von der Leyen’s speech to the World Economic Forum in Davos, January 16, 2024 at https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2024/01/ursula-von-der-leyen-full-speech-davos/ ↩

Henry Foy, James Politi and Ben Hall, “The West wavers on Ukraine,” Financial Times December 8, 2023 at https://www.ft.com/content/2447a4b4-bbff-4439-a96c-e3c5404ed105 ↩

Alexander Baunov, “The danger of losing focus on Russia’s war against Ukraine,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, January 17, 2024, https://carnegieendowment.org/politika/91398 ↩

Sam Meredith, “EU leaders say they can’t fully replace US support to Ukraine as funding fears grow,” CNBC, October 5, 2023, https://www.cnbc.com/2023/10/05/russia-war-eu-says-europe-cannot-replace-us-support-to-ukraine.html ↩

European Council conclusions, 14 and 15, European Council December 15, 2023, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2023/12/15/european-council-conclusions-14-and-15-december-2023/ ↩

“Ukraine 2023 Report,” European Commission, August 11, 2023, https://neighbourhood-enlargement.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2023-11/SWD_2023_699%20Ukraine%20report.pdf ↩

The Republic of Cyprus was able to join the EU despite Turkish occupation of its northern part because – since Turkey had achieved all its goals and Cyprus was incapable of resistance – Turkish forces halted their advance on August 18 1974 and no further significant conflict occurred. ↩

Figures at https://www.macrotrends.net/countries; Transparency International Corruption Perception Index 2021, https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2021/index/ukr ↩

Nahal Toosi, “Leaked U.S. strategy on Ukraine sees corruption as the real threat,” Politico, October 2, 2023, https://www.politico.com/news/2023/10/02/biden-admin-ukraine-strategy-corruption-00119237 ↩

Thomas Graham, “Hurdles on the Way to Ukraine’s EU Membership,” Council on Foreign Relations January 17, 2024, https://www.cfr.org/article/political-hurdles-ukraines-way-eu-membership?utm_source=tw&utm_medium=social_owned. ↩

In Germany, polls in late 2023 suggested that a slim majority (52 percent) of Germans still supported early EU membership for Ukraine, but this is before the concrete issues involved have been presented to the German public. “Political Barometer November 2023,” Forschungsgruppe Wahlen, November 24, 2023, https://www.forschungsgruppe.de/Aktuelles/Politbarometer/. ↩