You Can Go Home Again: A Proposal for Phased Military Withdrawal from Iraq and Normalizing U.S.–Iraq Relations

Executive Summary

March 2023 marks two decades since the U.S. invasion of Iraq. Saddam Hussein is long gone, memories of the post–invasion civil war are fading (from the American mind, at least), even as the large troop cohort that invaded Iraq, and later surged to stanch a spiraling insurgency that it helped create, have been redeployed. Parliamentary elections are routine, and the ISIS threat has been significantly degraded. The political and perceptual domestic and foreign costs of both intervention and withdrawal have, for the most part, already been incurred. The level of violence is much reduced and oil is flowing. The problems facing a new generation of Iraqis are largely economic, as massive protests in 2019 made clear, and a year–long effort to seat a government after the 2021 parliamentary election made it equally clear that the structure of Iraqi politics was both durable yet dysfunctional. The memory of the sectarian civil war that followed the U.S. invasion and the ISIS conquest of much of the country still looms large for Iraqis.

U.S. interests in Iraq are derived from an interest in regional stability and impel the continuation of an “advise, assist, and enable” mission in the near term. There is no need, however, to maintain a long–term military presence in the country. The United States must manage a delicate balancing act: While Iraq’s security forces have improved considerably, a sudden withdrawal of a substantial number of U.S. troops could halt or reverse these gains. On the other hand, the continued presence of U.S. troops in the medium term could erode Iraqi motivation to field a competent professional force and maintain readiness. With U.S. troops as a fail–safe against the rise of ISIS, Iraqi leaders might not be motivated to invest in their country’s defense. The perception that Washington is available to keep a lid on ISIS also frees up the IRGC (Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps), Iran–aligned militias, and the Gulf states to carry out their own agendas, which frequently run counter to U.S. interests.1

Disengaging militarily from Iraq will likely reduce U.S. influence in Baghdad and Erbil. Washington’s weight should not be exaggerated, but it is real and the presence of U.S. troops reinforces it. The new Iraqi government, led by Mohammed Shia al–Sudani, has publicly endorsed the U.S. military presence with the consent of his coalition partners. Nevertheless, bilateral diplomatic relations do not typically rely on U.S. deployed forces; normalization of the U.S.–Iraq relationship will ultimately entail the drawdown of U.S. forces. And as in all things, there will be diminishing returns to scale of the U.S. advise–and–assist program over time. The opportunity and transition costs of withdrawal will diminish proportionately.

The principal recommendation is to draw down the U.S. military presence over the next five years while helping Iraq to counter attempts by ISIS, or a similar iteration of the group, to exploit adverse social and economic conditions and destabilize the country.

We suggest the following steps to guide U.S. engagement with Iraq. It is based on our analysis of open–source data, academic literature, government and think–tank reports, and extensive interviews, conducted on and off the record, between May 2022 and February 2023 with current and former U.S. officials in the State Department, Pentagon, and White House, senior Iraqi security officials and politicians, community activists, and journalists. The principal recommendation is to draw down the U.S. military presence over the next five years while helping Iraq to counter attempts by ISIS, or a similar iteration of the group, to exploit adverse social and economic conditions and destabilize the country. The most the U.S. can reasonably expect to achieve is an improvement in the technical capabilities and professionalism of a select few elite units, while providing counsel to Iraq’s leaders, primarily through regular contact between the U.S. ambassador in Baghdad, Prime Minister al–Sudani, and other Iraqi stakeholders.

Recommendations

• Recognizing limits to the longer–term effectiveness and risks of advise and assist programs, begin to replace Operation Inherent Resolve, the current U.S. Central Command mission in Iraq, with a smaller contingent of advisors and special operators, consistent with a focused advise and assist program, organized around the Office of Security Cooperation–Iraq (OSC–I) based in Baghdad but with a small Title 10 mission under U.S. Central Command for the primary purpose of assisting with training and Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance (ISR).

• Withdraw all U.S. troops from Iraq within five years (except Marine Security Guards for the protection of the Embassy and OSC–I personnel under the U.S. Mission), recognizing that temporary combined training exercises, military delegations, and combined planning efforts using TDY personnel would be useful and should continue if both countries wish.

• Continue to develop the capacity of Iraqi partner forces, including the Counter Terrorism Service (CTS) and Federal Intelligence and Investigation Agency (FIIA), with an emphasis on mission planning and coordination, ISR, and combined arms capabilities. Push harder for coordination between these units and the Joint Operations Command for Iraq (JOC–I).

• Alternatives should be created for conducting training and joint military drills with Iraqi partner forces inside and outside of Iraq, including in neighboring countries and the United States, in order to compensate for the reduction of the quality of training for Iraq’s security forces as a result of the withdrawal. The NATO, Australia and New Zealand capacity building missions in Iraq should be stepped up as the U.S. effort draws down.

• In combination with European allies and regional partners, increase the resources necessary to mitigate the challenge posed by al–Hol and other ISIS dominated camps in Syria to support stability in northeast Syria.2

These recommendations offer a timeline for a significant reduction in U.S. troops toward a posture that is more focused on long–term training, similar to the U.S. military’s activities in other regional countries where relations are normalized, and the implementation of certain steps to ensure the degradation of ISIS in the short–term, the technical and organizational development of the most effective units within Iraq’s security forces, and a transition to more normalized U.S.–Iraq relations.

Introduction

The 20th anniversary of the U.S. invasion of Iraq raises the question, why are U.S. military forces still there? The Iraqi state appears to control the territory within its jurisdiction and its problems seem impervious to military solutions. A petrostate with such large reserves and a relatively small population has the resources to provide its citizens with a reasonable standard of living, adequate social services, a modicum of security, education for its youth, a functioning physical infrastructure, and a measure of administrative capacity to manage lesser issues, such as roadworks, and major ones, especially climate change. Yet none of these public goods appears to be available now, or in the foreseeable future. Given the rapid population growth and climate–induced migration from rural areas to the city, how Iraq will provide the necessary jobs and resources to support this growth is uncertain. The conundrum, of course, is that Iraq’s political structure precludes structural reforms.

Washington can contribute to Iraqi stability at the margins through economic and technical assistance, but it cannot engender stability

Moreover, sectarian distributional systems, such as Iraq’s, tend to create openings for meddlesome outside powers. Contending factions are eager to have the outsider’s thumb on the scale in their favor in local power struggles. In the Iraqi case, these outside powers include the United States, UAE, Qatar, Türkiye, and Iran. Saudi Arabia is important as well, but its impact on Iraqi politics and security is harder to discern. China is politically less significant in Iraq relative to other countries. Each has its particular interests and objectives vis–à–vis Iraq and each, to varying degrees, derogates from Iraqi sovereignty, while reinforcing adverse trends in Iraqi politics.

From the narrow perspective of this paper, this dour outlook raises two questions: Do Iraq’s seemingly intractable problems threaten U.S. interests, even obliquely? Does a continued U.S. presence in Iraq mitigate such a threat, and if so, does this outweigh its costs?

The answer to the first question is yes. To the degree that U.S. strategic interest is served by deprioritizing the Middle East region, instability in Iraq can impede this process. Feasible measures to stabilize Iraq now reduce the risk of instability in the future and therefore make military deprioritization a safer and more sustainable proposition. The risk to the broader strategic objective of deprioritizing the Middle East was illustrated by ISIS’s conquest of Iraqi cities in 2014. Although counterfactuals are generally unhelpful, it is not hard to imagine the impact on regional and European security had ISIS forced the removal or isolation of the Iraqi government. Under these conditions, whatever administrative capacity accumulated since the asteroid of the U.S. invasion struck Iraq would likely evaporate. A brutal civil war could recur, radiating transborder violence and inviting renewed outside intervention, which, in turn, would increase the wavelength of radiating violence — and involuntary migrants — to Europe and beyond. In this scenario, based on numerous discussions with current U.S. policymakers, the return to Iraq of a large U.S. expeditionary force under existing authorities would likely be a foregone conclusion. From a purely U.S. perspective, such a crisis would saddle an already brittle domestic political scene with yet another burden.

Would a continuing U.S. presence, especially on the modest scale endorsed here over the medium term, mitigate this threat? Again, we are in the realm of conjecture. At this juncture, ISIS in Iraq has been largely subdued. ISIS in Syria has not. This can be inferred from the 466 ISIS operatives killed in Syria by U.S. Central Command and its partner forces in 2022. The relatively open border between Iraq and Syria is a factor in any assessment of ISIS’s potential for resurgence in Iraq. It is also a problem that might be ameliorated through use of advanced surveillance and reconnaissance technologies. But the flawed governance that generated conditions for ISIS may hobble the state’s ability to respond to a cascading revolt in the future. This is exacerbated by the fact the Syrian state has no presence in the areas of the country where ISIS remains a threat that could spill over into Iraq.

The United States can improve Iraqi military capabilities such that a violent challenge by ISIS or similar groups to the Iraqi state can be contained or defeated.

Washington has limited influence on the quality of Iraqi governance or the integrity of its political process. Senior officials in the Biden administration clearly grasp this. Their low profile during the prolonged political crisis of October 2021 to October 2022 reflected the infeasibility of intervening publicly and intensively in that yearlong impasse. The U.S. embassy’s chief of mission statement, which emphasizes economic reforms and the impending tragedy of climate change, tacitly acknowledges these limits. Washington can contribute to Iraqi stability at the margins through economic and technical assistance, but it cannot engender stability. Robert Ford, the former Deputy U.S. Ambassador to Iraq, cautioned against the U.S. allowing itself to be sucked into Iraq’s political bargains.3

The United States can, however, improve Iraqi military capabilities such that a violent challenge by ISIS or similar groups to the Iraqi state can be contained or defeated. The ultimate purpose of U.S. military advice, training and assistance is simply to keep armed opposition groups in check and, if that effort fails, support an Iraqi military response that stanches an opposition offensive and relieves besieged population centers. Even in this limited respect, advise, assist and enable efforts do not typically produce miracles. Indeed, the U.S. track record in Latin America, East and sub–Saharan Africa, Syria and Afghanistan is uninspiring. But the purpose of the current program, or the proposed scaled down version, is not transformative. Rather the objective is to give Iraqi forces enough of an edge to keep ISIS, or like–minded challengers, down.4

This begs the question, for how long? An open–ended commitment undermines Iraq’s incentive to develop and maintain an independent capability, especially in the realm of logistics and, in the case of the Peshmerga, something as fundamental as the military payroll. It will encourage Iraqi government corruption and mismanagement since U.S. troops are viewed as a fail–safe against a complete collapse of security conditions à la 2014.5 An open–ended commitment also jams a future U.S. administration wishing to withdraw to focus on other priorities, as it will face accusations of betrayal, weakness, irresponsibility and loss of credibility. These disincentives lead to interventions that, in effect, never end. On the other hand, a predefined duration of the commitment invites adversaries to wait out the clock, while undermining the host country’s forces morale and commitment to fight.

The Islamic State is not an existential threat to the United States, but U.S. counterterrorism officials warn that it aims to carry out attacks against Americans at home and abroad.

These competing concerns are valid in principle but irreconcilable in practice. The prudent course therefore is to stipulate a time limit with a medium–term horizon of five years. This timeframe is sufficient for further incremental gains in Iraqi capabilities, particularly intelligence gathering, targeting, and mission planning, and far enough out to make waiting out the clock impractical for adversaries. It is also enough time to reduce collateral but important problems, particularly the fate of detainees at al–Hol and other ISIS holding camps in Syria managed by partner forces, which General Joseph Votel (retd.), who led USCENTCOM from March 2016 to March 2019, called “powder kegs for the next generation [of terrorist]” in an interview for this report.6 Likewise, it affords the Iraqi government a meaningful opportunity to enact necessary reforms or, at a minimum, improve the standard of living in sensitive areas susceptible to revolt. Splitting the difference has a checkered reputation as a policy outcome; sometimes, however, it is the best of all options — especially for an outside power attempting to hedge against inconvenient uncertainties. The cost to the United States of its current level of effort is quite small; 2,500 soldiers and Marines is an infinitesimal fraction of the total force. Given the size of this investment, even if the expected benefits are small, many voices in government believe the effort might still be worth making in the short–term.

The Islamic State is not an existential threat to the United States, but U.S. counterterrorism officials warn that it aims to carry out attacks against Americans at home and abroad. If such attacks were successful and believed to have originated in Iraq, our interviewees assessed that the U.S. response would entail much higher troop levels than is now the case. Hence they see a value in even a small deployment that can help detect and thwart such conspiracies.

The following analysis wrestles with these questions from an historical perspective and lessons learned since the U.S. withdrawal from Iraq in 2011, an analysis of current U.S. interest in a stable Iraqi state and U.S. capacity to protect its interest given the constraints imposed by domestic Iraqi politics and competing U.S. interests elsewhere. It warns of the inability of a long–term U.S. military deployment to positively address Iraq’s underlying structural deficiencies or advance U.S. interests, and instead offers a more sustainable path forward.

What Are U.S. Interests in Iraq?

Core U.S. interests in the region are to prevent any outside power from asserting hegemony and maintaining unimpeded flows of oil and gas. At this moment, there is no looming would–be hegemon and there are no near–to–medium term impediments to the flow of fossil fuels. Regional instability, however, is perceived as a threat to these core interests because it provides openings for outside powers and could, if left unchecked, drive energy prices upward. To the degree instability stirs jihadist activism, it could result in attacks against Americans. Although such attacks are not strategic in effect, U.S. political dynamics can cause them to be treated as though they were, driving large scale responses that do not serve U.S. interests.

U.S. interventions in the region, particularly the invasion of Iraq in 2003, have themselves become an accelerant of the very things they were intended to cure.

Regional stability is a general term, but includes concerns over terrorism, intra–state conflict, and mass migration. U.S. interventions in the region, particularly the invasion of Iraq in 2003, have themselves become an accelerant of the very things they were intended to cure. Interventions are costly and, where temporarily successful, solve a near–term problem at the expense of longer–term interests because getting out is harder than getting in. Since these aims are asserted to justify intervention, their elusiveness makes it hard to justify disengagement. In the post–war period, exit strategies devolved to cutting losses through hastily executed if unavoidable withdrawals. Although the domestic political costs to these departures have generally been less than anticipated, with the significant exception of Vietnam, they raise concerns about international perceptions of U.S. credibility, resolve, and even competence, which in turn heightens anxieties about deterrence and alliance cohesion. The lesson is clear: to the extent that the U.S. can reinforce stability, it must do so in limited, discrete ways and with an eye toward an orderly withdrawal.

Current State of Play

The United States has begun withdrawing from the Middle East and Central and South Asia, maintaining fewer troops in the regions than it did at the height of U.S. intervention between 2005–12, as other global interests have assumed greater importance. Washington’s partners and regional countries anticipate this trend will continue. The political and perceptual domestic and foreign costs of withdrawal have, for the most part, already been incurred. The U.S. military presence in the region has faded since the vast expansion of regional activism between the Reagan era and Obama’s first term. Large numbers of U.S. personnel — up to 20,000 — still circulate through the Persian Gulf region on rotating deployments; 2,500 troops remain in Iraq in the post–combat phase of the war against ISIS and 900 in Syria, where the U.S. fight against ISIS drags on.

Policymakers in the White House and Pentagon view the U.S. ground and air presence in Iraq and Syria as a means of suppressing ISIS’s ability to destabilize Iraq, to the extent that the United States would be impelled to intervene on a larger scale and with much greater violence. Although this paper is focused on Iraq, U.S. planners regard Iraq and Syria as a unified theater of operations because of the highly permeable border between them. The desire to prevent ISIS from once again flowing from Syria into Iraq has been a factor in the U.S. military presence in Syria, which increasingly looks to be a long–term feature of its regional footprint. The U.S. CENTCOM mission in Syria is also dependent on logistical support from Iraq. “Our ability to withdraw from Syria, as President Trump ordered in December 2018, was 100 percent dependent upon Iraq for success,” explained General Joseph Votel.7

The United States remains the most important enabler of Iraq’s security forces and largest single donor of humanitarian assistance to Iraq. The security it signifies in post–ISIS Iraq is the linchpin for many other missions which further U.S. interests in the country, including the United Nations Assistance Mission for Iraq (UNAMI) and World Food Programme, which had 652,774 beneficiaries in 2021.8 Germany, Japan, Canada, and various European countries donate tens of millions of dollars to Iraq annually.9 This support reflects the perceived security interests that some of Washington’s closest partners have in a stable Iraq.10 It was not long ago that ISIS wreaked havoc in European cities at levels not felt in the United States. A severe downturn in Iraq’s security and governance could complicate the delivery of such aid or end it altogether.

There is of course a surfeit of risks to Iraqi stability. Fiscal rigidity, corruption, hidden arrears, low labor force participation and high unemployment, an environmental crisis that is eroding food and water security, an internal migration from the impoverished countryside to cities lacking adequate infrastructure or labor markets and suffering from the worst effects of climate change, increased costs due to the Ukraine conflict, and dwindling social capital owing to the collapse of its educational system all suggest that Iraq’s budget surplus from oil, which has increased as a result of the war in Ukraine, will go just so far.11 This reality is exacerbated by the allure of expanding public sector jobs as a quick fix. The United States has a substantial USAID presence in Iraq consistent with Iraq’s status as a middle–income country, but its structural difficulties are well beyond Washington’s ability to help.

Al–Qaeda in Iraq’s Metamorphosis into ISIS

Resistance to the U.S. occupation formed quickly following the March 2003 invasion and creation of the Coalition Provisional Authority. U.S. troops’ restrictions on movements, excessive use of force, and killing of civilians fueled the formation of the insurgency. In parts of Baghdad and southern Iraq it was led by Moqtada al–Sadr, scion of a prestigious Shi’a clerical dynasty in Iraq. Within the Sunni–majority provinces, former Baathists and regime security forces formed one wing of the resistance and a loose coalition of Islamist and tribal insurgencies formed another.12 These Sunni groups worked together at varying times and overlap was common. Al–Qaeda in Iraq (AQI) was formally established in September 2004 and, for Washington, became the most organized and feared element of the Sunni insurgency. They were labeled “dead enders,” a term that carried a dual meaning. The one was that they had nothing to lose and were therefore profoundly committed to violent resistance and the other that they represented a soon–to–be–extinct species, pulverized by the juggernaut of democracy. In November 2005, some leaders in the heavily Sunni governorate of al–Anbar formed the Provincial [Anbar] Security Council to challenge the power grabs and excessive violence of AQI. But AQI launched a campaign of assassinations that dismantled tribal resistance. The group rebranded itself as the Islamic State of Iraq (ISI) in the summer of 2006 and shortly afterward announced the revival of the caliphate.

The formation of the “Anbar Awakening” movement was announced in September 2006. It too consisted of tribal leaders intent on fighting the ISI. The U.S. military encouraged the Iraqi government to deputize Anbar Awakening militiamen and provide them with salaries. This, combined with the firepower of U.S. Marines and soldiers, enabled the Anbar Awakening to oust AQI and its ISI offshoot from Anbari cities and towns by 2007. The Sunni–led militia known as the Sons of Iraq achieved similar successes in parts of Baghdad and other Sunni–majority governorates. These victories were the context for the U.S. decision to formally suspend its combat operations in August 2010. Plans for a full U.S. withdrawal were then made per the Strategic Framework Agreement and the Security Agreement with Iraq signed in 2008. The Obama administration and the Iraqi government of Nouri al–Maliki engaged in dialogue in a last–ditch effort to reach an agreement on an updated Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA), but by October 2011 the Iraqi government had rejected the idea. Without a SOFA, keeping U.S. troops in Iraq became untenable.13 The most violent phase of the Islamist insurgency was, however, just around the bend. Abu Bakr al–Baghdadi would announce the formation of ISIS and its new cross–border emirate on April 8, 2013. Ramadi, Fallujah, and Mosul quickly fell into ISIS hands thereafter.

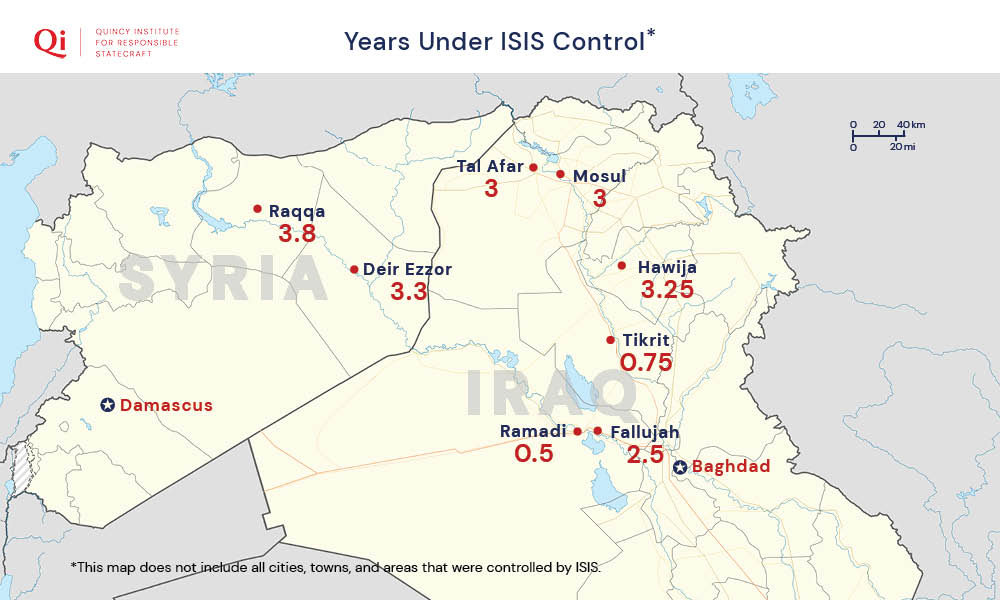

Conventional accounts of the rise of ISIS focus on President Obama’s decision to withdraw remaining U.S. troops from Iraq in 2011. A calendar–based timeline left Iraqi army units inadequately prepared to defend Iraqi cities and severed Washington’s eyes and ears on the ground and in the sky, which allowed the ISIS threat to gain strength before the United States could swing back into action.14 Several Iraqi cities lived under ISIS’ black flags for over two years, while the group planned and inspired deadly terrorist attacks abroad.

The suppression of the Islamic State of Iraq (ISIS’s predecessor) in 2008 owed more to domestic Iraqi developments than to Washington’s control of events on the ground. AQI’s founding leaders were Jordanian and Egyptian but the majority of its deputies and rank and file were Iraqi.15 Many foreign fighters participated in this “jihad” but were nonetheless a minority of the combatants. The leaders of the Anbar Awakening tribes and Sons of Iraq militia that fought ISI had strong reasons to do so: the insurgents were usurping their authority, taking over the informal economy, and disrupting a political order that vested authority in tribal sheikhs. The U.S. military applied political leverage in Baghdad and was a force multiplier on the battlefield. But Sunni resistance to AQI and its offshoots was the product of an organic Iraqi movement.

The unraveling of the Anbar Awakening and Sons of Iraq was likewise a product of Iraqi domestic politics and the impact of sectarianism. According to the U.S. Army history of the war, the blame lay with Prime Minister Nouri al–Maliki’s decision to arrest and kill members of the Sons of Iraq, arrest high–ranking Sunni political rivals and use the Special Tactics Units as a “hit squad” to eliminate other political rivals,16 while excluding those with links to the Ba’ath party, and effectively engineering the government formation after the 2010 parliamentary election results.17 This verdict is overly harsh. Maliki still had strong Sunni allies and Sunnis were overrepresented in his government. The Arab Spring inspired a Sunni sectarian wave and some of the Sahwa leaders ultimately rejected the legitimacy of any Shi’a–led government in Baghdad. Other Sunni tribal leaders of the Anbar Awakening perceived themselves to be in an impossible position just as ISIS was coalescing.18 If the tribes sided with the Iraqi government against ISIS militants, then they appeared as stooges of oppressive Shi’a politicians, but if they chose to break from Baghdad, then their resources and de jure legitimacy within the Iraqi government disappeared. This gave ISIS an edge.

Washington played an “essential moderating role among the rival Iraqi political groups,” but its control over the Iraqi government was limited.19 “Americans knew about the drawback of Nouri al–Maliki but looked the other way,” according to Robert Ford, who served as deputy U.S. ambassador to Iraq from 2008–10.20 The Anbar Awakening focused on AQI and later the Islamic State of Iraq as immediate threats, but always viewed itself as the protector of Sunnis against overreach and abuse by a Shi’a–dominated government in Baghdad. Maliki brought these fears to life and, by doing so, discredited Awakening leaders aligned with him in Anbar, Salah al–Din, and other governorates. AQI possessed the focus and discipline to exploit these divisions.

The Maliki government, the U.S. command in Baghdad, and the Obama administration failed to fully grasp the extent of the ISIS threat on the horizon.21 U.S. risk assessments focused on conflict between Arabs and Kurds, and on Iranian influence.22 Both the State Department and U.S. military commanders overemphasized the importance of Iran. In summer 2009, the U.S. military estimated that all Sunni resistance groups combined had no more than 3,500 fighters and possibly as few as 1,450 and by spring 2010 the figures for AQI alone were as low as 1,000 fighters.23 The Maliki government refused to accept that AQI was responsible for a series of suicide bomb attacks beginning in summer of 2009 and instead chose to scapegoat alleged Baathists and the Syrian government.24 Maliki prioritized electoral politics as ISIS began to take Iraqi cities with ease in late 2013. Some Shi’a militia commanders warned Maliki of the coming threat but they were ignored at first. The capture of Mosul, Iraq’s third largest city, necessitated the implementation of decisive measures by Baghdad, Washington, and Tehran alike.

The rise of ISIS presented an existential threat to the state of Iraq. Its AQI predecessor had occupied neighborhoods and highways, but ISIS effectively controlled entire governorates. President Obama initially viewed ISIS as a threat to Iraq, but not one of grave consequence to the United States or its close partners.25 His attitude changed as ISIS began to execute U.S. citizens, inspire attacks abroad, and engage in brutal crimes in Iraq. Obama worried that ISIS’s growing ability to engage in transnational terrorism could produce ripples far greater than the attacks themselves. He observed, “[i]t is not just the threat they pose to the homeland, but it is the distortionary effect they could have on our politics if we have an attack here.”26

In 2014, these developments led to the launch of Operation Inherent Resolve (OIR) to liquidate the ISIS threat. For the next three years, intense fighting to liberate Iraq’s cities was led by an unlikely, and sometimes uncoordinated, loose coalition of U.S. troops, regular Iraqi army, federal police, specialized units such as the Counter Terrorism Service, and Iran–aligned militias organized as the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF). It culminated in the retaking of Mosul, which saw U.S. troops in direct action and at least two fatalities. Iraqi security forces took heavy casualties with 1,320 killed and 6,880 wounded during the nine–month long battle.27 The recapture of Mosul from ISIS marked a decisive blow to their self–styled caliphate, but Washington’s delayed entry into the fight hurt U.S.–Iraq relations and boosted favorable perceptions of Iran, which not only fostered the PMF but sent some of its most senior commanders to the frontline.

Iraq’s Security Forces Today

Iraq has a hybrid army composed of both regular and paramilitary units.28 The regular military units, such as the Iraqi Army and the Iraqi Air Force, are professional military forces. The paramilitary units, on the other hand, are often made up of irregular volunteers. These units, such as the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF), are equipped by the government, but operate somewhat independently of the regular military; some of them receive training and funding from Iran. They are, however, formally in a chain of command culminating in the prime minister, with the exception of resistance factions that exist as Shi’a paramilitary units outside of the prime minister. The federal police also function as a powerful paramilitary force and played a large role in fighting ISIS.

The Islamic State’s takeover of Mosul, and the subsequent collapse of Iraq’s security forces, necessitated a restructuring of the country’s armed forces. In the early months of 2014, many units within Iraq’s security forces collapsed or fled in the face of the ISIS advance. This led to the formation of the PMF and greater importance of the Counter Terrorism Service (CTS).

The impetus for the PMF was Grand Ayatollah Ali al–Sistani’s June 2014 fatwa calling for citizens to fight ISIS. Although the majority of the PMF units are Shi’a, Sunni units do exist and have been effective in preventing the resurgence of ISIS. Some of these militias were newly formed and others had existed since before the U.S. invasion in 2003. Although the PMF are part of Iraq’s force structure and under the command of the prime minister, they operate in parallel to the regular military.

The CTS is a specialized branch of the Iraqi security forces trained and equipped for counter–terrorism operations. It was formed in the aftermath of the 2003 U.S.–led invasion of Iraq and has played a key role in the fight against ISIS and other terrorist groups in the country. The CTS proved particularly effective in the fight against ISIS under Lieutenant General Abdul–Wahab al–Sa’adi. It played a consequential part in the liberation of Mosul. “The Iraqi response was largely built around the CTS with whom we stayed partnered after our withdrawal in 2011. This small investment meant a lot in 2014,” said General Joseph Votel.29 The CTS also works with the Federal Intelligence and Investigation Agency (FIIA) which, apart from collecting intelligence, also plays a role in counter–terrorism and is subject to the oversight of the Prime Minister’s Office. While the CTS has been an essential partner in the battle against ISIS, our discussions revealed that the CTS is increasingly hesitant to conduct operations in heavily PMF– controlled areas lest it run afoul of powerful Iran–backed stakeholders. Ambassador Tueller shared that the CTS’s approach to reigning in PMFs is often to find a way to avoid conflict, or as he described it, “in many cases, it’s well, let’s find a way to not step outside the bar tonight.”30

During General Votel’s tenure as CENTCOM commander, he discussed with Iraqi Prime Minister Haider al–Abadi the potential of transitioning the PMF militias into a corps of engineers focused on public works; however, this did not come to fruition.31 Recent reporting indicates that the PMFs are increasingly making use of the Ministry of Defense’s resources to train and develop their officers.32 It is yet to be determined whether this will be used to bolster the PMFs as an autonomous body that challenges the authority of the state, or to incorporate them into its command structure.

The U.S. Footprint in Iraq Today

Approximately 2,500 U.S. troops remain in Iraq today. In 2022, U.S. Central Command conducted 313 total operations against ISIS, mostly partnered with local forces, killing 466 ISIS fighters in Syria and at least 220 in Iraq.33 The United States has been using military force in Iraq and Syria under the authority of the Authorization for Use of Military Force (AUMF) passed by Congress in 2001 in the wake of 9/11 and the AUMF passed in 2002, which was specific to Iraq. Consecutive U.S. presidents have also relied on their Article II powers to justify continued counter–terrorism activities in Iraq and Syria even without the AUMFs.34 Today, U.S. troops remain in Iraq at the invitation of the Iraqi government based on the U.S.–Iraq Strategic Framework Agreement that was first signed in 2008. Prior to becoming Assistant Secretary of State for Near Eastern Affairs, Barbara Leaf described the framework as having “elegantly wrapped the U.S. military mission in legality.”35 Washington and Baghdad’s commitment to the Framework Agreement was reinforced during the Strategic Dialogue initiated by the Trump administration in June 2020 and concluded by the Biden administration in July 2021. Prime Minister Mohammed Shia al–Sudani reaffirmed Iraq’s request for the continued presence of U.S. advisors without specifying a timetable.36

Approximately 2,500 U.S. troops remain in Iraq today.

Operation Iraqi Freedom was the name of the military operation launched by the United States and the coalition in 2003 to remove the government of Saddam Hussein from power. The ground operation was launched on March 20, 2003, and officially ended on December 18, 2011, when the last U.S. troops left Iraq (although they would return in 2014). The United States continued to deploy advisors and trainers to assist the Iraqi military in its efforts to maintain security and stability after the end of Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF), but the failure to reach a new Status of Forces Agreement meant that a Office of Security Cooperation–Iraq, which was supposed to number in the thousands, was reduced to approximately 200 U.S. military personnel.37

Operation Inherent Resolve (OIR) is the military campaign the United States and the coalition have conducted against ISIS since 2014. It began when the United States and its allies began conducting airstrikes against ISIS targets in Iraq. Over the following years, the operation expanded to include the deployment of U.S. and allied ground troops to Iraq and Syria, as well as the training and support of local forces. By the end of 2021, U.S. combat operations in Iraq formally ended and transitioned to a mission to advise, assist, and enable Iraqi partner forces.38 As of 2022, ISIS has been largely suppressed, and Iraqi–led operations have entered a new phase focused on stabilization and reconstruction in areas formerly controlled by the group, while continuing to raid small holdout positions in sparsely inhabited areas in the west and ungoverned spaces along the boundary separating the Kurdistan Region from the rest of Iraq.

The 2,500 U.S. troops remaining in Iraq today are organized under OIR and the Office of Security Cooperation in Iraq (OSC–I). The primary function of U.S. troops in Iraq today is to train and advise Iraq’s security forces to increase their ability to operate independently. OIR “hangs its hat” on the Iraqi Joint Operations Command for Iraq (JOC–I) which is responsible for planning and conducting military operations, as well as coordinating the efforts of various Iraqi security forces.39 But the JOC–I is generally unwilling to coordinate with the Counter Terrorism Service, which leads to complications.40 The JOC–I prefers airstrikes over artillery due to the risk of collateral damage, but Iraqi pilots still lack the confidence to conduct their own targeting. This is also true for the CTS, which remains heavily reliant on the United States for Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance (ISR). The U.S. military presence in Iraq also serves as the linchpin for the D–ISIS campaign in Syria, where U.S. troops are still involved in direct combat and stationed at bases in the northeast and southeast, where they work with Syrian partners.

The United States cannot substitute for the political legitimacy of the host country’s government, the will of its armed forces to fight, or the national pride required to defeat an insurgency.

The United States faces two major challenges in providing security force assistance and building partner forces in Iraq and Syria. The principal–agent problem presents the United States with conflicting interests between itself and its partner, varying risk thresholds, and limited monitoring and control.41 Excessive reassurance to partner forces can cause them to believe U.S. support will never decrease, while insufficient reassurance is demoralizing and reduces the U.S. importance in calculations. Additionally, the messaging from U.S. leaders to justify continued deployments of U.S. troops and high expenditures to taxpayers often exaggerates the importance of the recipient country, leading it to believe it is vital to U.S. interests and too important to be left behind. Both of these dysfunctions were apparent in the collapse of Afghanistan’s security forces during the U.S. withdrawal. Washington’s partners in Baghdad also create a challenge, as Iraqi leaders perceive a well–trained and structured military as a threat to their power. To counter this, Saddam Hussein and Nouri al–Maliki both implemented strategies to weaken the regular army and incorporate the most reliable units and personnel into their direct command.42

The United States cannot substitute for the political legitimacy of the host country’s government, the will of its armed forces to fight, or the national pride required to defeat an insurgency. Previous attempts at partner force building have been hindered by a common set of challenges: a lack of non–commissioned officers, ghost soldiers, weak motivation, and human rights abuses.43 While cases such as Korea44 and El Salvador45 may be cited as examples of successful security force assistance, the importance of political factors is often underestimated. The United States has been unable to transfer legitimacy to the governments it has established in its post–9/11 wars, and an insurgency is often able to take advantage of the legitimacy vacuum left by the state.

Despite the widely accepted notion that nation–building is a futile endeavor, U.S. doctrine still holds aspirations for it.46 Yet security assistance should not be considered a miniature version of nation–building. While focusing on elite units such as the Afghan Commandos and Iraq’s Counter Terrorism Service47 has resulted in competent partners, they are not going to replace the machinery of the state. The most the United States can reasonably expect to achieve is an improvement in the technical capabilities and professionalism of a select few elite units, while providing counsel to Iraq’s leaders, primarily through regular contact between the U.S. ambassador in Baghdad and Prime Minister al–Sudani.

Iraq’s Domestic Politics: Fleeting Alliances and Rivalries

Iraq is a federal parliamentary republic with an elected unicameral legislature called the Council of Representatives. The president is elected by the Council of Representatives and appoints the prime minister, who is the head of government. Government formation is typically a time–consuming process of log–rolling. It took 156 days after the 2005 elections, 249 days in 2010, 131 days in 2014, 144 days in 2018, and 382 days after the most recent October 2021 elections to form a government. Coalition governments form disjointed administrations, as ministries are assigned as part of political compromises, resulting in competition between ministries to serve the interests of different political parties and individual leaders, rather than achieving a unified national agenda.

Most political parties in Iraq are formed along ethnic and sectarian lines that are sometimes paired with a particular Islamist or secular ideological leaning. More precisely, most of Iraq’s political parties are organized along Arab, Kurdish, and Turkmen ethnic lines, and Sunni and Shi’a sectarian lines. These might be Islamist, secular, populist, or some combination of the three in their ideological orientation. Since the 2010 elections, new coalitions have been formed that bridge sectarian divisions.48 Some of Iraq’s political parties and coalitions can also be differentiated by the closeness of their relations with foreign powers, in particular Iran and the United States. For example, the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) and the Shi’a political bloc known as the Coordination Framework have closer ties to Iran than do their respective political rivals. The Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP), on the other hand, is particularly close to the United States. Even these relationships are complicated. For example, former president Barham Salih is a PUK politician, but worked closely with U.S. officials, and Moqtada al–Sadr, who leads the Sadrist movement, has at times sought refuge in Iran while also challenging its influence.

The return of exiled Shi’a parties

In 2003, the United State’s decision to remove Saddam Hussein from power altered the existing power dynamics in Iraq, which had disproportionately favored the country’s Sunni Arabs. The Shi’a make up a majority of Iraq’s population, with estimates ranging from 55 to 60 percent.49 The political power of this small majority is magnified by the fact that the remaining Sunni population is divided between Arabs (24 percent), Kurds (15 percent ), and Turkmen (1 percent), whereas most of Iraq’s Shi’a are Arab.50 The Coalition Provisional Authority’s Iraqi Governing Council featured a majority of Shi’a to reflect the nation’s demographics, establishing a consociational structure in which parties campaigned on the basis of ethnic or sectarian identity and the ability to capture state resources for their communities rather than on the allocation of resources that would advance both communal and national objectives.

The U.S. occupation facilitated the return of exiled movements, including the Supreme Council for Islamic Revolution in Iraq (SCIRI), the Badr Organization, and the Dawa Party. Iraq’s new sectarian order, Dawa’s astute parliamentary politics, and its good relations with Washington contributed to three of its politicians attaining the office of prime minister by 2018. The absence of a militia also enabled Dawa’s rise to power, as it was initially perceived as not posing a threat to those with armed wings. Dawa’s followers have become informally divided between two of these former prime ministers — Nouri al–Maliki and Haider al–Abadi. Iraq’s other returned Shi’a parties were less politically agile and more prone to splintering. SCIRI changed its name to the Islamic Supreme Council of Iraq (ISCI) in 2007 and later shifted toward less revolutionary positions under the leadership of Ammar al–Hakim. In 2017, al–Hakim left ISCI to form the al–Hikmah (National Wisdom) Movement, which seeks to transcend sectarian boundaries while maintaining its Shi’a roots. The Badr Organization emerged from SCIRI in 1982 and split from it fully in 2012.

Unlike Dawa, however, other Shi’a political movements expressed their power outside of electoral politics through militias, which they often integrated into the Iraqi government structure to extract resources and protect their interests. For example, in 2005, Bayan Jabr, a former Badr commander, was appointed as Iraq’s Interior Minister, bringing an estimated 16,000 Badr militia fighters into the security forces of the Ministry of Interior; some of these formed the Special Police Commandos.51 Badr officers and fighters remain integrated in Iraq’s Ministry of Interior.52 At the same time, they also form a large part of the PMF. The emergence of ISIS and Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani’s fatwa to mobilize Shi’a men to resist the group ushered in a new player in Iraq’s factional Shi’a politics, the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF). This coalition of Shi’a militias, many of which have been receiving support and training from Iran, was formed to counter ISIS, and has since become deeply entrenched in Iraq’s economic, political, and social fabric. Former Prime Minister Adel Abdul Mahdi officially incorporated the PMF into the Iraqi state’s command structure, but they remain largely autonomous.

Moqtada al–Sadr, intra–Shi’a political conflict, and the 2021 elections

The Sadrist movement in Iraq, led by firebrand cleric Moqtada al–Sadr, has its roots in the religious network of organizations and charities established by his father, Ayatollah Mohammed Sadeq al–Sadr. His assassination by the Saddam regime in 1999, while other Shi’a leaders had fled the country, valorized the Sadr family name among Iraq’s Shi’a underclass, and underwrote the movement’s resurgence following the U.S. invasion in 2003.

Following 2003, Moqtada leveraged his family’s reputation to create one of the most influential Shi’a political movements in the country. Religious legitimacy, however, remains with the Najaf–based Grand Ayatollah Ali al–Sistani, the highest–ranking Shi’a cleric in Iraq. The Sadrists’s emergence as a formidable homegrown political movement led to tensions with returning elites. Sadr’s militia, the Mahdi Army, also tested the U.S. military in the early 2000s. In 2014, the Mahdi Army was renamed the Saraya al–Salaam (Peace Companies), and subsequently engaged in the fight against ISIS. Since 2009, Sadr positioned the movement as an expression of Iraqi nationalism and open to coalition building.

This paid off in the run–up to the 2021 Iraqi parliamentary elections. Moqtada al–Sadr formed his own multi–ethnic and cross–sectarian coalition, which included Sunni politician Mohammed al–Halbousi and his Taqqadum party, as well as Masoud Barzani’s Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP). Sadr hoped this coalition would allow him to grab power by forming a majority government. The coalition did win the majority of seats in the October 2021 elections, but the Coordination Framework, a political bloc that includes the political representatives of the PMFs, impeded the formation of a government. The Framework’s obstruction was abetted by a Supreme Court ruling that removed the option of electing a president through a simple majority in a second parliamentary vote if the first vote failed to pass by a two–thirds majority, which was the case. As a result, Sadr’s coalition was unable to form a government as it could not command the required two–thirds majority.

In response to the impasse, Sadr ordered the resignation of all 73 of his MPs and sent his followers to occupy the parliament building, leading to a violent protest. It appeared he was hoping the Sunni and Kurdish blocs of his coalition would also resign. Instead, they defected from Sadr’s coalition and the 73 parliamentary seats he vacated reverted to the Coordination Framework. The political process went forward with Mohammed Shia al–Sudani’s appointment as prime minister. The Sadrist challenge was conclusively turned aside and, barring any surprises, there will not be an election for another three years.

Moqtada Sadr’s stance against Iran–aligned militias won praise from those who viewed him as a wedge against Iran’s influence, or as an opponent of an allocative political structure that had outlived its usefulness.53 A more accurate view might be that he is immune to any influence, including that of his own advisors, and engaged in a power grab.54 Ambassador Tueller assessed that an interest in avoiding a violent intra–Shi’a conflict is a rare point of commonality between Tehran and Washington in Iraq.55

Arab Sunni political stagnation

The Arab Sunni community experienced a profound reversal of fortune in 2003. De-Ba’athification, a U.S. policy that removed members of Saddam Hussein’s ruling Ba’ath Party from government, and the demobilization of the Iraqi military weakened the very institutions that were essential to the reconstruction of the Iraqi state.

De–Ba’athification also removed a secure source of income for tens of thousands of Arab Sunnis employed by the state — an Iraqi iron rice bowl. The purged soldiers returned home with arms and ammunition, which later proved to be useful for insurgents. The response to the ascendance of the Shi’a in Baghdad was to reject electoral politics until the late 2000s. In 2005, the turnout for the parliamentary elections in Mosul, a predominantly Sunni city that would later be captured by ISIS, was only 10 percent.56

In the current political landscape, Arab Sunni power depends on the ability of individual politicians to navigate coalition dynamics and cultivate relationships with their Shi’a counterparts. Sunni politicians can have a substantial impact on Iraq’s parliamentary politics, as Mohammed al–Halbousi showed in the last election. Nonetheless, many Sunnis clearly believe they do not benefit in proportion to their needs and numbers.57 How much of this is due to discrimination in the corridors of power versus the nature of the system can be difficult to assess. Southern Iraq, which has a large Shi’a population, is poorly served, even in major cities such as Basra.58 And outside the cities, in, say, the marshes where climate change has decimated the local fishing industry, the central government has been absent.

Iraqi Kurdistan: The runner–up in the post–2003 political order

The KDP and PUK have long been rivals. In the 1990s, they fought a civil war for control of the region. The conflict ended in 1998 with the signing of the Washington Agreement, which established a power–sharing arrangement between the KDP and PUK, with the KDP controlling the northern part of the region and the PUK controlling the south. Significant friction exists between them, and Washington is still viewed by both parties as a mediator whose influence is necessary to maintain intra–Kurdish cooperation.59

The U.S. invasion of 2003 and removal of Saddam Hussein eliminated the primary threat faced by Iraqi Kurds. But it also forced the KRG to grapple with federalism, disputed territories, and the new political order emerging in Baghdad. The fight against ISIS was a boon for the Kurdish independence movement in that the Peshmerga were able to move into previously disputed territory, including Kirkuk. Warm relations between Washington and Erbil and significant U.S. financial support for the Peshmerga has not always translated into U.S. influence over the KRGs actions. In 2017, despite strong protest from Washington, a non–binding Kurdish independence referendum was held in the KRG. The referendum, which was pushed by the KDP with some misgivings from the PUK, was overwhelmingly approved, with 92.7 percent of voters casting their ballots in favor of independence.

In response, the central government of Iraq, with the support of the PMF, launched a military operation and retook control of Kirkuk. The status of the disputed territories and legal disputes of the sale of oil and natural gas remains a thorn in KRG–Baghdad relations. Kurdish leaders firmly believe that Washington’s prolonged military and diplomatic presence in Iraq is essential in order to safeguard their autonomy and further their objectives in relation to Baghdad. Washington continues to view the KRG as the most dependable and secure region of Iraq, thus overlooking rampant corruption and lack of reform.

The Tishreen movement and non–reform

Approximately 70 percent of Iraq’s population is under the age of 30 and nearly half is younger than 18. According to the World Bank, 36.9 percent of Iraqi youth are not in education, employment, or training and even those with jobs are typically underemployed.60 In October 2019, the Tishreen movement in Iraq inspired thousands of young people to protest corruption, lack of job opportunities, and inadequate public services. Demonstrations in Baghdad, Basra, Nasiriyah, and Najaf were met with a violent response from the Iraqi security forces. Hundreds were killed and thousands injured. An Iraqi government pledge to form an independent commission to investigate the deaths of protesters and other reforms has yet to be fulfilled.

The Tishreen movement garnered much enthusiasm from Iraqis eager for reform and some Western commentators who viewed it as a spur to genuine transformation. But without effective leadership, it failed to evolve from a grassroots protest movement to a political party. Many Tishreenis refused to engage in a tainted political process, making it difficult to channel discontent into programmatic change.61 Whether the demographic youth bulge will seriously threaten the political order, or be disempowered by brain drain, unemployment, and cynicism is unclear. In the interim, however, Tishreeni discontent is not to be discounted.

Executing a Withdrawal and Normalizing U.S.–Iraq Relations

U.S. military planners are well–equipped to handle the logistics and costs directly associated with the withdrawal of troops and equipment from Iraq and the gradual transfer of facilities to the Iraqi government, and these considerations fall outside the scope of this paper. This paper recommends specific actions to enable the withdrawal of U.S. troops, place the U.S. Mission in Iraq back at the core of U.S.–Iraq relations, and plan for contingencies to protect U.S. interests within a five–year timeline.

These actions fall under three broad categories:

• Furthering the continued development of Iraqi partner forces.

• Establishing a sustainable post–OIR assistance and training framework.

• Defining and advancing U.S. diplomatic objectives.

Continue to develop Iraqi partner forces

Since its inception in 2014, Operation Inherent Resolve (OIR) has been divided into four phases: Degrade (2014–15), Counterattack (2015–16), Defeat (2017–20), and Normalize (2020–present).62 The desired end states of OIR are classified, but the 2022 Campaign Plan of Combined Joint Task Force — Operation Inherent Resolve (CJTF–OIR) defined the general conditions as “ISIS is unable to resurge in Iraq and Syria; the ISF is able to independently provide security and stability in Iraq; and eastern Syria is stable and secure.”63 This paper has identified the desired end state as a short–term U.S. interest that requires an equivalent level of resources, without the need for a permanent presence of U.S. troops. Over the next five years, the U.S. focus should be on enabling Iraqi partner forces to achieve an acceptable level of competence and readiness, with the utmost emphasis placed on operating independently from mission planning to execution. When it comes to security force assistance, the perfect is very much the enemy of the good.

Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance (ISR) is the U.S. military’s “most critical enabler” of its Iraqi partner forces.64 Published assessments have concluded that the ability of the Counter Terrorism Service, a key U.S. partner in the battle against ISIS in Iraq, to “independently execute the targeting cycle is limited.”65 In the last reported quarter, CJTF–OIR evaluated that the CTS have moderate competency when conducting operations against ISIS independently; however, with the support of the Coalition, the CTS are often effective. Members of U.S. Security Force Assistance Brigades are also deployed as advisors to Iraqi and Peshmerga units to focus on more rudimentary skills according to interviews with senior U.S. military officials.66

The U.S. focus should be on enabling Iraqi partner forces to achieve an acceptable level of competence and readiness, with the utmost emphasis placed on operating independently from mission planning to execution.

In contrast to many other countries, Iraq’s security forces report to multiple chains of command within the Ministry of Defense and Ministry of Interior. Additionally, the Counter Terrorism Service operates independently as a cabinet–level entity reporting directly to the prime minister. Supporting and liaising with Iraq’s security forces is particularly challenging due to this disjointed and polyhierarchical structure. The U.S. military should, therefore, focus on the CTS and Federal Intelligence and Investigation Agency, with an emphasis on mission planning and coordination, ISR and targeting, and limited combined arms capabilities. This will require greater U.S. pressure on the Joint Operations Command for Iraq (JOC–I) and units like the CTS to coordinate. U.S. advisors should also consider what standard operating procedures and technology are most likely to be adopted independently by partner forces. Attempting to instill best practices that require indefinite U.S. hand–holding or replicate the culture and capabilities of elite U.S. units in partner forces has proved ineffective.

Establishing a sustainable assistance and training framework

Currently, U.S. troops remain in Iraq in a training and advisory role, with the majority of troops operating under the Combined Joint Task Force — Operation Inherent Resolve. As Operation Inherent Resolve enters its final phase, steps should be taken to transition to a smaller contingent of advisors and special operators, consistent with a focused advise and assist program, likely organized around the Office of Security Cooperation–Iraq (OSC–I) based in Baghdad under its Title 22 mission. Simultaneously, OIR should transition to a smaller Title 10 mission of a few hundred personnel, who will provide training and sustain ISR capabilities.67

OSC–I was established in December 2011 as a Security Cooperation Organization (SCO), which is a DOD element located in foreign countries that is responsible for executing security cooperation and security assistance management functions.68 It is a Title 22 organization that has received some Title 10 funding and straddles the divide between the U.S. Mission in Iraq and the Department of Defense.69 OSC–I, a part of the U.S. Mission in Iraq that reports to the embassy’s Chief of Mission, sometimes operates as a bridge between the mandates of Title 10 and Title 22, and exists at the crossroads of the Department of Defense and State Department’s mission, particularly in the context of the ongoing D–ISIS campaign.

The authors of this paper are mindful of the limitations of OSC–I , or any SCO, and lessons learned from OSC–I’s experience in Iraq between 2010–14. Established in December 2011 amid a failed negotiation of a new Status of Force Agreement (SOFA) with Iraq and an increasingly defiant Prime Minister Nouri al–Maliki, OSC–I was understaffed and disconnected from the U.S. Mission in Iraq.70 OSC–I was expected to compensate for the loss of a Title 10 mission while under a Title 22 mandate, which was very difficult.71 Nevertheless, OSC–I maintained the connective tissue between the Iraqi security forces and U.S. government after the last U.S. combat troops left Iraq in 2011.72 The presence of OSC–I enabled the U.S. military and Iraqi security forces to rapidly respond to the threat posed by ISIS in 2014. But it is imperative to avoid repeating the errors made in 2011 by expecting OSC–I to execute activities outside of its Title 22 mandate and those for which it was not designed.

OSC–I cannot replicate the capabilities of CJTF–OIR, and it is not reasonable to expect it to. A U.S. military presence in Iraq primarily led by OSC–I would represent a genuine transition away from a U.S.–Iraq relationship centered on military ties. But to be effective after OIR comes to an end, OSC–I will require a broad mandate so it can engage with the various elements of Iraq’s security forces across different ministries and agencies. It will also require enough manpower to conduct routine and enhanced end–use monitoring of the Iraqi security force’s inventory of Stinger surface–to–air missiles, night–vision devices, and other sensitive weapons systems. The Department of Defense should consider implementing preferential leave policies for unaccompanied tours to encourage OSC–I staff to volunteer for consecutive rotations. If safety conditions improve, then accompanied tours should be considered at OSC–I and other SCOs. Lastly, OSC–I will require a small Title 10 CENTCOM component consisting of no more than several hundred troops that can operate in parallel, and at the invitation of the Iraqi government, by providing training and enhanced ISR capabilities to specialized Iraqi units like the CTS. This small Title 10 component will succeed OIR and act as a glidepath to enable Iraq’s partner forces to develop greater mission planning, combined arms, and ISR capabilities before U.S. troops leave within five years. By maintaining distinct Title 22 and Title 10 missions, the United States can provide the most effective support to Iraqi partner forces while minimizing the number of troops in the country, as each mission can be tailored to the specific requirements, thus avoiding a bloated OSC–I or burdening it with tasks beyond its capabilities. By no means should any U.S. troops in Iraq be used in combat.

During this transitional period, Iraqi partner forces will likely require sustained training from the United States and its coalition allies. They will also need assistance through ISR to adequately prevent a regeneration of ISIS or a similar group. In 2011, upon the assumption of the responsibilities of Multi–National Security Transition Command — Iraq (MNSCTC–I) by OSC–I, it was evident that the organization was overstretched and unable to provide adequate training. The Jordan Operational Engagement Program (JOEP) could serve as a potential model to be replicated, albeit with a more focused and robust structure. Established in 2014, the JOEP provides 14–week individual and collective training sessions in marksmanship, tactical first aid, map reading, land navigation, battle drills, improvised explosive devices, and other combat skills to the Jordanian Armed Forces (JAF).”73 The DoD Global CT Train and Equip Program (Sections 1206 & 2282) was approved in early FY 2015 by Congress, with $11.2M in support dollars allocated to support the JOEP.74 Training of partner forces in the region undertaken through Operation Spartan Shield also provides a potential model, as does U.S. military support for the UAE, which includes Title 22 and Title 10 components.75

The major expenditures of the U.S. defense budget in Iraq encompasses the direct costs of Operation Inherent Resolve, the Counter ISIS, Train and Equip Fund (CTEF), and formerly Title 10 support for the Office of Security Cooperation–Iraq, though this has been transferred to other agencies in recent years. In FY 2022, $7 billion was enacted for Operation Inherent Resolve and $5.5 billion was requested for FY 2023.76 This budget refers to direct costs of the advise, assist, and enable mission with local partner forces in Iraq and Syria. For comparison, $27.3 billion was enacted for FY 2022 for “Other Theater Requirements and Related Missions” in the Middle East, South Asia, Horn of Africa, and Guantanamo. An overall reduction of –$1.5 billion in USCENTCOM’s operational budget request from FY 2022 to 2023 was attributed to the shift towards an advise, assist, and enable role in Iraq.77

A smaller contingent of advisors and special operators, as outlined in this paper, and the transition to a more targeted advise and assist program, with the OSC–I as its core and a smaller Title 10 component over the course of five years, could result in future budgets of hundreds of millions of dollars, rather than billions. Transitioning from OIR as it exists today to a smaller Title 10 component in Iraq alone would likely save billions.

The other two largest components of future expenditures would be direct support for the OSC–I and the continuation of the Counter ISIS, Train, and Equip Fund (CTEF). The Department of Defense requested $36.8 million to support OSC–I in FY2018, $45 million in FY 2019, $45 million in FY 2020, $44 million in FY 2021, and $30 million in FY 2022.78 Funding of OSC–I has transitioned from the Department of Defense to other agencies. In the last four reported quarters, $563 million has been spent on Iraq–specific CTEF expenditures.79 Figures 1 and 2 illustrate the quarterly and annual distribution of CTEF funds in Iraq, with stipends to pay the salaries of Peshmerga personnel representing the largest single expenditure. The agreement struck by Baghdad and Erbil on the 2023 federal budget provides for Peshmerga salaries, so U.S. funding might no longer be required.

To reduce the long–term risks of an open–ended intervention, recentering U.S.–Iraq relations around the U.S. diplomatic mission in the country, ending Operation Inherent Resolve, and transitioning to a smaller train and advise mission organized around OSC–I and a small Title 10 component over the next five years is a necessary trade–off, even though it may result in short–term operational risks. A successful transition will require the U.S. military to devise innovative strategies, such as sustaining counterterrorism operations through ships, monitoring potential threats via surveillance and censors, and acting as a bridge between the Iraqi security forces and other regional and international stakeholders to provide support. The Ukraine war has offered valuable insights into how a limited U.S. advisory mission can significantly empower a militarily undeveloped nation. While not all of these lessons can be applied to Iraq, some can. These goals will be best served by avoiding direct confrontation with Iran or Iran aligned militias, unless they attack U.S. infrastructure or personnel.80 Most importantly, U.S. diplomacy within Iraq and the region must be dynamic, calculated, and bold.

Defining and advancing U.S. diplomatic objectives

U.S. diplomacy in Iraq will be best served by engaging with all actors within Iraq’s government and society to the extent they are willing to engage, former foes and current antagonists included. The U.S. Mission should speak directly to Iraq’s people about issues that matter to them, such as the economy, climate change, and education. This requires the United States to seek new ways to distribute non–military assistance directly to Iraqi recipients and direct aid to projects and NGOs that support the interests of younger Iraqis; and effectively communicate to everyday Iraqis how U.S. support improves their lives.

Conclusion: A Way Forward for U.S.–Iraq Relations

As Iraq enters 2023, its government has achieved a degree of stability, though it has proven to be largely ineffective at day–to–day governance. The sectarian tensions that have plagued the country have abated, but the presence of Shi’a militias in predominantly Sunni areas, the perception of an unequal distribution of resources, and instability in Syria all contribute to a fragile peace.81 Iraq’s economy is far from its potential, with the majority of its young population excluded from the wealth enjoyed by a select few elites. Only Iraqis can resolve these problems. The United States does, however, have the ability to help the Iraqi government contain an ISIS resurgence that might be facilitated by this biblical list of intractable problems. U.S. policymakers should avoid the self–fulfilling prophecy of a withdrawal predicated on conditions they can never attain. But just five–and–a–half years ago, ISIS controlled much of Iraq’s third largest city; a resurgence is well within the realm of possibility. It is therefore in the U.S. interest to continue to buttress Iraq’s security in the near term while simultaneously planning for a phased off–ramp from the current mission.

U.S. diplomacy within Iraq and the region must be dynamic, calculated, and bold.

In discussions with U.S. policymakers about the U.S. interest in Iraq, two themes frequently appear in addition to countering ISIS. One is that a U.S. military presence in Iraq hems in Iranian efforts to dominate the political space. This, in turn, invokes a second theme, which is the presumed U.S. interest in sustaining its own influence in key capitals on the Arab side of the Persian Gulf. These themes are linked by a reputational concern that drives U.S. security strategy more generally. But maintaining a U.S. military presence for these reasons is fallacious at best. No small U.S. military presence is likely to overcome Iran’s influence in Iraq, which is based on deep communal, cultural and geographical connections and which Tehran views as a vital interest. The linkage between a continued U.S. military presence in Iraq and Gulf Arab confidence in the United States qua security guarantor is also overstated, insofar as Saudi and Emirati foreign policy appears to have discounted the U.S. factor already.

Staying the course without developing a clear exit strategy increases the probability of a hastily executed withdrawal in the future.

Committing to an open–ended U.S. military presence in Iraq at current troop levels may be an attractive course of action for policymakers given its low upfront cost and the relative stability of the status quo. It also allows for a rapid increase of troops should the need arrive. This discounts, however, long–term uncertainties relating to Iraq’s political development, U.S. domestic politics, and the emergence of new military threats that would make even a minimal footprint in Iraq untenable. Staying the course without developing a clear exit strategy increases the probability of a hastily executed withdrawal in the future. U.S. interests in Iraq compel the continuation of an “advise, assist, and enable” mission in the medium term but do not warrant an extended U.S. military presence.

Executing a medium–term drawdown while sustaining support in the short–term is a difficult needle to thread for U.S. policymakers and military planners. The U.S. experience in Afghanistan and redeployment of troops to Iraq in 2014 gives U.S. leaders pause over their inability to anticipate events. But the circumstances of Iraq and Afghanistan are so different that few insights can be gleaned from a comparison. The writ of the state extends to nearly all of Iraq. While Mosul’s rapid fall demonstrated that this is not to be taken for granted, Iraq in 2023 is a far cry from Afghanistan in 2021. ISIS and the Afghan Taliban both took advantage of poor governance, communal grievances against the central government, and a legitimacy crisis, but that is where the similarities end. The Taliban’s ideology and strategic discipline confined the movement’s ambitions largely to Afghanistan itself. This in turn lowered the threat perceptions of outside actors. The Taliban also proved adept at diplomatic outreach and negotiations. None of this can be said about ISIS.

U.S.–deployed forces in Iraq now hover around 2,500, down from 158,000 in 2008 and a peak of 495 U.S. military installations across the country. They are a legacy of an interventionist era. Their numbers have declined as U.S. perceptions of its capacities and interests have converged with undeniable geopolitical realities. The fragility of Iraq and the permeability of its borders, however, make renewed violence both possible and transmissible. The U.S. assistance and training mission has improved the Iraqi government’s ability to maintain order and lower the risk of broader conflict that could create immense political pressure to pull significant U.S. troops back in.

The proposal outlined here — small in size, limited in duration, and leveraging allied participation — offers a glide path toward a normalized, non–military relationship with the Iraqi state.

Unlike Afghanistan, a severe setback in Iraq will have a corresponding negative political valence at home. The strategic stakes will be bid up in a partisan competition for political advantage. This actuality puts a premium on practical things the United States can do to help Iraq stay on an even keel. The proposal outlined here — small in size, limited in duration, and leveraging allied participation — offers a glide path toward a normalized, non–military relationship with the Iraqi state.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Quincy Institute for supporting multiple research trips in Iraq and the United States and to professors F. Gregory Gause, Marsin Alshamary, and Nir Rosen for their critique of the draft text. We are also indebted to Mohammed Dhia al Sharwani who helped facilitate research trips to Baghdad and Erbil in the spring and fall of 2022.

Program

Entities

Citations

Iraq’s Shi’a population, outside of elites, generally does not share the perception that the United States did much to defeat ISIS in Iraq. ↩

This refers to the resources needed to run the camps in a humane manner and repatriate former ISIS families to Iraq, Syria, other Middle Eastern countries, and Europe. ISIS is also present in Deir ez–Zor and has a covert presence in Raqqa, hoping to wait out a U.S. withdrawal. ↩

Robert Ford was U.S. ambassador to Syria from 2011 to 2014 and deputy U.S. ambassador to Iraq from 2008–10. QI interview, October 2022. ↩

In a QI interview General Joseph Votel (retd.) explained, “the nature of our current mission in Iraq is really focused on [improving the capabilities of] Iraqis and not so much on ISIS.” ↩

The Peshmerga are the military force of the semi-autonomous Kurdistan Regional Government. ↩

QI interview with General Joseph Votel, Nov. 10, 2022. ↩

QI interview with General Joseph Votel, Nov. 10, 2022. Votel added that the Syria mission would be severely compromised if the United States withdrew from Iraq, but the al–Tanf component of the mission could be supported from Jordan so long as the Jordanians would continue to cooperate. Votel assessed that a drawdown in Iraq would probably occur in tandem with a drawdown in Syria. ↩

World Food Programme. “Annual Country Report 2021: Iraq.” 2022. https://www.wfp.org/operations/annual-country-report?operation_id=IQ02&year=2021#/22518. ↩

United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs Financial Tracking Service. “Iraq 2021,” 2022. https://fts.unocha.org/countries/106/donors/2021?order=total_funding&sort=desc; see also Jalabi, Raya. “International help for Iraq.” Reuters, March 21, 2018. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-iraq-mosul-official-help/international-help-for-iraq-idUSKBN1GX19I. ↩

Matthew Tueller, who served as U.S. ambassador to Iraq from June 2019 to June 2022, emphasized in a QI interview, “what isn’t fully appreciated is of course since 2014 our presence there has enabled this global coalition. More than 90 countries and international institutions, organizations have signed up to be part of this global coalition to defeat ISIS. And it’s really only in Iraq where they’ve got that global force. About 12 of the countries actually contribute to presence on the ground. And of course, without the U.S. there in that enabling role, both just in terms of logistics and presence, but also the political enabling, that would dissipate immediately.” QI interview with Ambassador Matthew Tueller, October 6, 2022. ↩

While the Ukraine conflict has increased the prices of some goods it has also led to a bloated budget due to high oil prices. ↩

Stansfield, Gareth. Iraq. Malden. Polity Press, 2016. 182–3. ↩

U.S. officials interviewed for this paper believed that negotiating a SOFA is still not tenable, but the Strategic Framework Agreement is sufficient. According to Robert Ford, U.S. ambassador to Syria from 2011–14 and deputy U.S. ambassador to Iraq from 2008–10, a new SOFA is unlikely but Tehran will tolerate a U.S. presence so long as there are no permanent bases and it is not used as a launch pad against Iran. According to Khalid Al–Yaweir, U.S. officials should focus less on reaching a final agreement with the Iraqi government and instead agree on some things but leave the door open to further negotiations. QI interview with Khalid Al–Yaweir, October 17, 2022. ↩

40 percent of U.S. Central Command’s ISR in Iraq was sent to Afghanistan. ↩