Desecuritizing the Belarusian Balcony: Principles for U.S.–Belarus Relations

Executive Summary

This brief outlines a low-cost, low-risk roadmap for sustained U.S. engagement with Belarus that could help to stabilize NATO’s volatile eastern flank, enabling the U.S. to retrench from the European continent and focus on other theaters.

In light of governance concerns voiced by Western officials on the heels of the 2020 Belarusian presidential election, and especially since Belarus provided support to Russian troops in the opening weeks of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, the E.U. and U.S. have adopted a strictly punitive approach to Belarus. Essentially, Belarus has been viewed as an appendage of Russia.

However, this approach misses opportunities for the West to take advantage of inherent divisions between the interests of Belarus and Russia. As outlined in previous Quincy Institute research, President Aleksandr Lukashenko of Belarus has long wished to develop a “multi-vector” foreign policy for his country.

Such a policy would permit Belarus to maneuver between the East and West to best safeguard its own national sovereignty and interests. While Belarus has moved significantly closer to Russia in recent years, this pivot has in part been in reaction to Western hostility. Lukashenko likely remains open to some degree of cooperation with the West, and has signaled that he does not wish to increase participation in the Russia–Ukraine War.

While it is almost certainly impossible to fully remove Belarus from the Russian camp, exploring ways for Belarus to triangulate between Russia and the West could offer significant benefits for U.S. interests and for regional stability. This brief recommends that the Trump administration explore the following bargain with Belarus:

- In exchange for a Belarusian commitment not to abet, facilitate, or engage in aggression against any NATO state, the U.S. should promise that it will not engage in any effort at an external change of government in Belarus.

- To firm up the U.S.–Belarus relationship, the U.S. should consider sectoral sanctions relief, including in the Belarusian civilian aviation sector, and U.S. engagement in other non-military investment opportunities, such as the Belarusian electric vehicle industry. The U.S. should also work to restore Belarus’ access to international financial institutions.

- The U.S. should mediate border issues between Belarus, Poland, and Lithuania toward the goal of deescalation on NATO’s eastern flank.

- The U.S. should encourage Belarusian efforts both to facilitate Russia–Ukraine peace talks, such as exchanges of prisoners of war and bodies of fallen soldiers, and to contribute to Ukraine’s postwar reconstruction.

Introduction

The White House’s decision to reengage Belarus, marked by Gen. Keith Kellogg’s June visit to Minsk, reflects a welcome recognition that the policy inherited by President Donald Trump from the previous administration has been counterproductive.1

The underlying reasons for this shift are as clear as they are compelling. The U.S. did not articulate and pursue a discrete Belarus policy for the vast majority of the post–Soviet period. Washington’s approach to Belarus has instead been dictated by shifting regional priorities, including efforts toward nonproliferation, democratization, and competition with Russia. The latter, in particular, has made it difficult to assess Belarusian interests in ways that make productive engagement possible.

Since the Soviet collapse, American strategic discourse has too easily resorted to the belief that Belarus must be forced to choose between Russia and the West, and that Minsk should be isolated as long as it takes for it to make the “correct” choice. This approach never fully took into account the geopolitical realities confronting Belarus and misread President Aleksandr Lukashenko’s chief foreign policy objective, which was to triangulate between Russia and the West in a bid to preserve Belarusian sovereignty on the best possible terms.2

Contrary to long-held assumptions, Lukashenko has always maintained — and continues to be guided by — a grand strategy of shaping Belarus as a multi-vector state that, though aligned with Russia in certain respects, is nonetheless free to cultivate its own relationships with Western countries based on Belarusian national interests. Belarus demonstrated a clear capacity for geopolitical flexibility after the Georgia and Ukraine crises in 2008 and 2014, respectively, but its continued ability to maneuver between East and West hinges on reciprocal positive signals from the U.S. and European capitals.3

Yet relations between Minsk and the West reached new lows after the Belarusian presidential election of 2020, which prompted a wave of condemnation from Western officials stemming from rule of law and civil society concerns. Belarus’ role in providing passage and logistical support to Russia in its 2022 invasion of Ukraine spurred a larger diplomatic rift between Belarus and the West. Washington joined most European countries in imposing a maximum-pressure program aimed at isolating Belarus, forcing Lukashenko to abandon his long-standing geopolitical balancing act between East and West and to instead double down on his ties with Russia, China, and much of the non–Western world.

The West has diminished its own leverage and undermined its regional posture by adopting a punitive and ultimatum-based stance toward Belarus, hurting American interests in the process.

The U.S. can neither effectively nor conclusively retrench from Europe and reallocate scarce resources to other theaters, as the Trump administration seeks to do, as long as NATO’s eastern flank is rent by conflict and volatility. The Russia–Ukraine War remains by far the most pressing regional problem, but there cannot be long-term stability on NATO’s eastern flank while Belarus remains locked in an escalatory spiral with its neighbors. Yet the Belarus crisis need not be a thorn in America’s side; a format for a win-win diplomatic resolution is ripe for the taking. Moves to rip Minsk out of Moscow’s orbit have been counterproductive and dangerous to regional stability because they ignore or try to override Belarusian geopolitical realities instead of working within them. The administration’s strategic vision toward NATO’s eastern flank is best advanced by an approach that treats Belarus neither as a potential bulwark against Russia nor as Moscow’s appendage, but instead one that embraces multi-vector politics as an attractive option not just for Belarus but for other post–Soviet states between Russia and Europe.

The logic and history behind Belarus’ long-standing attempts to carve out a niche as a geopolitically flexible actor in Eastern Europe, and the extent to which Belarus has been able to effectively play this role in prior years, were covered in depth in a previous Quincy Institute brief.4

This paper offers a policy roadmap for engaging Belarus as a sovereign actor that, like a number of other post–Soviet states, maintains close ties to Russia but nevertheless has its own reasons for seeking better relations with the West. The U.S., in turn, has clear reasons for resetting relations with Belarus and can do so in low-cost, low-risk ways that generate an immediate windfall for American diplomatic, economic, and security interests in the region.

Belarus as a European actor

It is admittedly counterintuitive to ascribe a central significance to U.S.–Belarus relations. It can be argued, not wholly without justification, that Belarus is chiefly a European concern, and that the onus should be on E.U. leadership and individual European states to correct the ineffective approach of the past decade. A number of intervening aspects should be considered here. To the extent that the U.S. has played a key role in enabling and sustaining the maximum-pressure sanctions on Belarus, Washington is as much a stakeholder in this as Brussels. The E.U. resolved to punish Minsk for its role in providing passage and logistical support to Russian troops in the opening weeks of Russia’s invasion by adopting a practice of “mirroring” its Russia sanctions program against Belarus.

While there is a creeping realization among European diplomats that the current policy has not borne any fruit, the political linkage that Brussels first established between Russia and Belarus makes it difficult for Europe to reform its approach to Belarus without feeding into the perception that E.U. leaders are wavering in their commitment to isolate Russia for “as long as it takes.”

The Trump administration operates under an entirely different set of assumptions about the Russia–Ukraine War and the region more broadly. It is seeking to end the conflict through a negotiated settlement that generates the conditions for a U.S.–Russia rapprochement, and, in stark distinction to the previous administration, it is not beholden to a broader democratizing agenda that treats the Lukashenko government as ipso facto illegitimate and unacceptable. The U.S. is thus ideally positioned to break the current diplomatic deadlock with a framework for reengaging Belarus. The E.U. posture toward Belarus would be rendered increasingly untenable by an initial U.S.–Belarus thaw that includes diplomatic normalization and sanctions relief, giving European leaders the political cover they need to build on the space created by proactive U.S. diplomacy.

Belarus’ most pressing foreign policy challenges lie not with Brussels but with two of its neighbors, Poland and Lithuania, which have increasingly adopted policies since 2020 that treat Belarus as a security threat and inveterately hostile actor.5Deescalation between Belarus and its NATO neighbors is squarely in Europe’s security interest, but European leaders have tied themselves to Baltic and Polish attempts to securitize Belarus in a way that compromises their ability to facilitate constructive engagement with Minsk. This, too, opens a space for mediation that only the U.S., as an offshore balancer with outsized influence within the NATO alliance, can fill.

The administration’s June overture to Belarus sent a clear message that Washington regards the present state of U.S.–Belarus relations as suboptimal and is interested in working with the Lukashenko government to improve them. Minsk’s decision to release 15 more prisoners, including a prominent opposition leader, follows a sequence of similar actions since 2025 intended in part to signal goodwill to the Trump administration.6The diplomatic momentum generated by contacts between Washington and Minsk — leading to Kellogg’s visit to Minsk and lengthy meeting with Lukashenko — is substantial, but it is equally important to acknowledge that these nascent efforts will run into a diplomatic dead end unless accompanied by a larger framework for sustained, long-term engagement.

The Russia factor

U.S. reengagement with Belarus, if framed accurately, can complement rather than clash with the Trump administration’s efforts to deescalate tensions with Russia. Washington should convey to Moscow, as early and clearly as possible, the thinking behind what it is looking to achieve. The goal is not and should not be to force Belarus’ Euro–Atlantic integration, which would spur aggressive Russian counterbalancing behavior and, if taken far enough, risk direct Russian military intervention.7Nor should the U.S. look to repeat the mistakes of the past by conditioning reengagement on a rollback of Russia. Rather, the U.S. should engage Belarus as a sovereign multi-vector state that, like Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan, seeks amiable relations with the West in ways that do not alter the regional security landscape so as to increase NATO’s offensive power against Russia. Indeed, it’s the other way around: This model for bilateral engagement is beneficial for the U.S. precisely because it allows the West to resolve regional security concerns without extending the Western security umbrella or upsetting the regional balance of power in any way.

Principles for U.S. policy toward Belarus

The first point of departure in any effort to reset the U.S.–Belarus relationship is to assess interests, incentives, and points of friction. Belarus is a key staging ground between NATO and Russia, making it an actor of outsized importance on issues of both nuclear and conventional force posture in the region. One prerequisite for ensuring regional stability is to foreclose potential challenges stemming from this Belarusian “balcony” facing the West to the greatest extent possible.8Previous Western attempts to accomplish this vital task have failed because they conceptualized Belarus’ future in binary terms as either an appendage of Russia or as a full-fledged member of the Euro–Atlantic community. Belarus, within this strain of political thought, should be democratized and eventually absorbed under the Western security umbrella to act as a bulwark against Russia on NATO’s eastern flank. This posture, far from stabilizing the region, has exacerbated security spirals between Belarus and its neighbors, encouraged aggressive Russian balancing behavior, and prompted Minsk to offset Western pressure by developing deeper ties with Moscow and Beijing.9

The chief lesson of the past five years has been that attempts to turn the Belarusian balcony on Russia have been counterproductive to any genuine sense of long-term U.S. or NATO interests in the region. The goal should, instead, be to desecuritize the balcony to the greatest extent possible by treating Belarus less as part of any bloc and more as the pivot player that it has long aspired to be.

Lukashenko — not unlike his counterparts in Azerbaijan and the Central Asian states — has long pursued the working concept of a multi-vector foreign policy that aims to maneuver between East and West to preserve Belarus’ independence on the best possible terms.10U.S. policy should aim to engage Belarus precisely along these lines — as a sovereign actor seeking to maintain constructive relations with the West without severing its well-established historical ties to Russia. The kind of relationship that can emerge from this arrangement falls well short of the post–1991 geopolitical orientation chosen by Poland, the Baltic states, and other eastern flank countries that saw their future firmly as part of the Euro–Atlantic — i.e., Western — community. Yet, far from a liability, it is advantageous from the perspective of U.S. interests to be able to pursue a limited liability relationship with Belarus that requires no new security commitments and offers the U.S. a low-cost, low-risk outlet for staying engaged in the region.

Belarus insulated itself from the imposition of Western sanctions after 2020 by doubling down on its economic ties not just with Russia but with China and much of the non–Western world.11Minsk’s strategy for mitigating the pain caused by Western sanctions has allowed China to establish a firm economic foothold in the geographical center of Europe, including in critical sectors such as manufacturing, transportation, and biotechnology.12This highlights not just the ways in which the Western sanctions program failed to achieve its intended results, but puts into focus the negative externality that ceding relatively large and critically positioned markets to China can hamper U.S. global competitiveness. By contrast, Belarus’ reintegration into Western markets would unlock its potential as a logistics hub between Europe and Asia, giving U.S. and European firms a fresh access point to the Eurasian northern corridor and providing additional freight transit routes to parts of Asia. A more diversified Belarusian economy thus offers a range of direct and indirect benefits for American and European economic interests.

Belarus’ foreign policy since 2020 has been centered on state preservation. This approach has two prongs: fending off ongoing challenges stemming from Western punitive measures and pursuing a long-term grand strategy that positions Belarus as a sovereign state actor in Eastern Europe. It is perhaps unsurprising, considering the pressures Belarus has come under, that the latter goal has been largely overshadowed by the immediate demands of the former.13Western attempts to isolate Minsk left it with little choice but to double down on security, political, and economic ties with Russia, something it previously resisted in favor of a more diversified approach. Multi-vector politics is by definition impossible in a setting where Belarus is completely blocked by one of two sides — in this case, the West — from acting as a pivot player.

Yet there remain clear indications that Minsk has not wavered in its desire to restore a constructive relationship with the West — its only real hedge against what would otherwise be Belarus’ one-sided reliance on Russia. “I want us to have normal relations. On my side there is only one thing: Don’t interfere in our garden,” Lukashenko said. “Do not interfere with our lives, and we will be good partners. We are ready for anything that does not contradict our interests and the interests of our allies. If you do not bend us over your knees, we will quickly reach an agreement.”14

Despite the substantial Russian military buildup on its territory, Belarus has foreclosed the possibility of entering hostilities against Ukraine and repeatedly stipulated that its security relationship with Russia does not extend beyond obligations of collective defense.15Belarus has also scaled back a major round of upcoming military exercises with Russia as a show of goodwill aimed at promoting regional deescalation.16

Belarus has no interest in letting itself be used by Russia in a war of aggression against its NATO neighbors, something Minsk recognizes would have catastrophic implications for Belarusian statehood. Put differently, Minsk and the West have a shared interest in working toward the kind of regional stability that can come from desecuritizing the Belarusian balcony.

Belarus maintains a variegated table of interests toward Europe. Though Minsk unquestionably benefits from visa facilitation agreements, certain forms of sanctions relief, and other legal items that can be agreed only on an E.U. level, its immediate and most pressing policy priority is to repair relations with its Polish and Lithuanian neighbors. There are several reasons for this. Border flows with these two countries are one of the lifelines of the Belarusian economy, and sustaining a format not just for deconfliction but stable defense dialogue is in the core security interest of all three countries.17Finally, to the extent that Poland and the Baltics bear an outsized role in supporting and sustaining the E.U.’s maximum-pressure policy against Minsk, Belarusian leaders calculate that steps toward a détente with these eastern flank states would generate spillover effects for its relations with the E.U. and its Franco–German core.

Belarusians generally see themselves as part of a common Western cultural sphere, and, though Minsk will never fully relinquish the economic ties with non–Western states that it has painstakingly cultivated since 2020, Belarus has a substantial economic interest in diversifying its consumer and producer markets with access to Western capital, goods, and financial institutions. Belarusian consumption and spending patterns prior to the imposition of full-scale Western sanctions suggest quite clearly that, everything being equal, many Belarusians will opt for Western, including American, products if given the choice.18

A roadmap for constructive U.S.–Belarus engagement

The U.S. diplomatic portfolio is rife with foreign conflicts where a deal, if one is to be struck at all, must be forced with a mix of outside pressure and cajolement. A potential U.S.–Belarus reset is not one such instance. To the contrary, there is such an impressive degree of overlap in core interests and so few diplomatic sticking points that a settlement, if approached holistically and pragmatically, can be reached relatively swiftly.

There need not be a “grand bargain” between Washington and Minsk in the sense of a single draft agreement that simultaneously resolves all the economic, security, political, and diplomatic components of what a reset would entail. The White House should, however, work with its Belarusian counterparts to arrive at a roadmap that outlines the steps to be taken by each side in a group of separate but functionally interrelated policy clusters. It should be clearly communicated to the Belarusian side that this is a reciprocal process; namely, that the U.S. is committed to repairing bilateral ties, but that sustained long-term progress hinges on Belarus’ ability to implement and abide by the packages agreed between U.S. and Belarusian negotiators.

Security cooperation

The first and most crucial element of these agreements, which opens a path to constructive engagement in all other areas, is the security cluster. It is important here to approach negotiations with a realistic assessment of where exactly U.S. interests lie and what Belarus is willing to do. Any agreement contingent on the ejection of Russian troops and weapons systems or the closure of Russian military bases on Belarusian territory is a nonstarter for Minsk. Even if it were somehow accepted by Belarus, such an arrangement would carry serious unintended consequences. Namely, it would jeopardize Washington’s negotiating posture with Moscow not just over Ukraine but in the broader U.S.–Russia deconfliction and normalization track that President Trump is pursuing, and it would incentivize aggressive Russian balancing behavior that would likely cancel out, in its destabilizing effects, any strategic benefits gained by a reduction of Russia’s force posture in Belarus. Even subtle security limitations, such as the closure of Belarusian airspace to Russian military assets, remain a red line for Minsk and thus should not be part of the negotiations.

Fruitful cooperation should instead start from the larger principles of European security on which Minsk and Washington agree. Belarus has repeatedly claimed that it harbors no aggressive intentions toward its Western NATO neighbors.19It would be a major boon for U.S. regional interests to secure this commitment as part of a written agreement. Belarus should formally commit not to abet, facilitate, or engage in aggression against any NATO state. This commitment should extend to hybrid cross-border operations, including any paramilitary groups operating out of Belarusian territory. This formula goes a long way in neutralizing any direct threats to NATO posed from the Belarusian balcony, and it does so without risking a security spiral with Russia or compromising the White House’s ability to engage Moscow on Ukraine and other issues. Indeed, such an agreement does not contradict any of Belarus’ current treaty obligations to Russia, which are purely defensive.

These agreements should be bolstered by an array of verification and confidence-building measures, including more robust deconfliction dialogue between Belarus and NATO and the ability of both sides to act as observers in certain military exercises. Washington and Minsk should restore a format for cooperation in a host of security-adjacent areas, including but not limited to anti-terrorism, human trafficking, drug threats, and other forms of international crime.20Washington should consult with allies about restoring Belarus’ participation in NATO’s Partnership for Peace program, which offers a ready-made blueprint for cooperation in these areas. Other opportunities include disaster management, search and rescue, emergency assistance, and scientific cooperation.21

The U.S. should, as part of its commitment to build a cooperative relationship with the Belarusian government, promise in turn that it does not and will not engage in any externally-induced change of government in Belarus. The White House should further clarify that, while it cannot prevent private actors from conducting lobbying activities in Washington related to Belarus, the only formal relationship it recognizes is the official one between the U.S. and Belarusian governments.

This set of agreements would defuse the historical driving points of tension between Belarus and the U.S., facilitating a format for effective wider reengagement.

Economic ties

The Belarus sanctions program, as outlined above, has achieved none of its intended results and left U.S. interests worse off in tangible ways. This does not mean that sanctions should be lifted without any preconditions, though here, too, it is important to exercise prudence. Any sanctions relief that is explicitly premised on the egress of non–Western firms from Belarus will be rejected. The U.S. should instead posit that, because it is the first and, for the foreseeable future, only Western country to take a decisive step toward economic reengagement, it is reasonable for U.S. companies to be offered preferential terms for doing business in Belarus. Precise arrangements will vary across and even within industries, but possible formats include tax breaks, grants, and subsidized land access for U.S. manufacturers that set up shop in Belarus. Such arrangements can generate a particularly attractive business climate for U.S. automakers. Belarus is heavily engaged in the electric vehicle industry, both on the consumption and production sides.22This specialization creates a unique potential space for many U.S. companies that have branched into electric vehicles, some of which are manufactured abroad at competitive prices.23

U.S. firms can invest in or help develop Belarus’ globally competitive potash sector and other resources as part of a revenue-sharing scheme that can be expanded, if relations proceed along a constructive track, into a U.S.–Belarus investment fund.24Belarus’ civilian aviation sector has been severely impacted by sanctions, setting the table for attractive opportunities in aircraft leasing, servicing, the export of spare parts, and cooperation in related areas.25A loosening of restrictions on Belarus’ aviation sector would be contingent on a mutually agreed understanding, subject to verification, that any aircraft or spare parts sold by the U.S. to Belarus will not be resold, donated, or otherwise transferred to any non–Belarusian entity.

Sanctions relief is best handled in a graduated, sectoral format that paves the way for relevant U.S. firms to do business in Belarus, starting with products, services, and industries that offer the most lucrative investment opportunities and do not hold any military application. The U.S. should also offer to help restore Belarus’ access to international financial institutions, particularly development organizations, in exchange for preferential terms on the arrangements discussed above.

Belarusian officials and the broader population remain skeptical that the U.S. is willing to commit itself to a long-term policy of bilateral reengagement. Removing some targeted sanctions against individuals on the Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons list, as well as freezing certain sectoral sanctions, would demonstrate good faith in the opening stages of negotiations without compromising U.S. leverage.

Promoting dialogue on humanitarian issues

As President Trump noted in May, it should not be a goal of U.S. policy to remake the world in America’s image. “In the end, the so-called ‘nation-builders’ wrecked far more nations than they built — and the interventionists were intervening in complex societies that they did not even understand themselves,” Trump said. “As I have shown repeatedly, I am willing to end past conflicts and forge new partnerships for a better and more stable world, even if our differences may be very profound.”26

This sense of healthy pragmatism is continuously applied by U.S. diplomacy around the world, including in the post–Soviet space with countries such as Azerbaijan and the Central Asian states. There is no reason why the same sensibility cannot serve as a guiding principle for a successful U.S.–Belarus reset.

Nevertheless, it is important to acknowledge that Western attempts to democratize Belarus through pressure and isolation have failed to yield human rights progress over the past five years. Insofar as these punitive measures have severed Belarus’ connection with the West and forced it to deepen ties to non–Western countries, the sanctions have progressively disincentivized the government from entertaining domestic reforms. The record of the past several decades unambiguously reflects that periods of rapprochement, rather than sustained pressure, have historically been accompanied by human rights progress inside Belarus.27President Lukashenko’s decision to release scores of prisoners on the eve of Gen. Kellogg’s visit to Minsk further underscores the positive feedback loop between constructive engagement and human rights.28

Yet it is neither in the U.S. nor in the Belarusian interest to allow a potential human rights track to be derailed into a tit-for-tat scheme whereby Minsk releases a certain number of prisoners in exchange for specific kinds of sanctions relief. This kind of relationship is undesirable because it generates perverse incentives to prevent a human rights dialogue from taking off, and it threatens to overshadow the advancement of more pressing U.S. interests in the security and economic clusters. It should be recognized as a point of policy departure that the Lukashenko government will not release all prisoners charged in connection with political cases. Elevating this as a central issue is unnecessary and counterproductive in the scope of what the U.S. should be trying to achieve, and, if presented as a hard precondition for substantive progress in other areas, would become a diplomatic poison pill for bilateral reengagement.

It is, however, prudent not to dismiss this issue altogether from the perspective of paving the way for a broader sociocultural reset between Belarus and the West. The most productive way forward is to engage Belarusian leaders in the spirit of the 1975 Helsinki Accords, which carved out a separate space for respectful, open-ended dialogue on civil society issues in addition to economic and security issues. This dialogue, which can be supported by Track 2/1.5 working groups in Belarus, Europe, and the U.S., should proceed at its own pace and without being linked to other U.S. policy priorities toward Belarus and the region.

U.S. mediation between Belarus and NATO’s eastern flank

Belarus’ hostile relations with its Polish and Lithuanian neighbors cannot be a matter of indifference to U.S. interests, as one of the central reasons for engaging Minsk in the first place is to promote regional stability. Warsaw and Vilnius have blamed the Lukashenko government for facilitating large volumes of migrant inflows through adjoining countries as a way of destabilizing the European Union.29Warsaw has attempted to secure its side of the border through heavy-handed measures that have drawn the ire of European officials and outside observers.30The border crisis has left Poland, which stands to benefit substantially from a normalization of cross-border trade and transit, with few good options. Meanwhile, a creeping militarization of the Polish–Belarusian border, replete with accusations of airspace violations and hybrid sabotage operations, presents tangible risks of feeding into a security spiral on NATO’s eastern flank.31

There is much too great a deficit in trust and goodwill between Belarus and its Western neighbors, especially amid the Russia–Ukraine War, for these issues to be effectively addressed in a bilateral way — or trilateral, between Belarus, Poland, and Lithuania. The grievances accumulated between these countries since 2020 require a kind of outside mediation that the European Union is not well-positioned to provide.32This opens a diplomatic space for the U.S., which has a vested interest in deescalation on NATO’s eastern flank and is the only other stakeholder with the bandwidth to fill such a role.

The U.S. should discreetly convey to Polish and Lithuanian allies that it is in the interest of all parties to resolve their differences in a forward-thinking, solution-oriented way. Washington should offer not just to host separate dialogues between Belarus and its Western neighbors, but to take the additional step of proposing an initial set of deconfliction measures. If Belarus guaranteed to do its part in putting a complete, verifiable end to irregular migrant outflows and any other malign hybrid activity from its territories, then its neighbors should commit to a roadmap for streamlining border crossings, including removing bottlenecks that have led to wait times of up to several days for freight traffic.33This arrangement complements and would be supported by the larger desecuritization measures that would be negotiated bilaterally between the U.S. and Belarus. A defusion of tensions between Belarus and its neighbors would not just be inherently beneficial for American interests but, to the extent that the U.S. is the only country with the diplomatic resources to drive this process forward, would offer the White House additional leverage in its other dealings with Minsk.

Belarus, Russia, and the Ukraine peace process

Any policy that explicitly conditions U.S.–Belarus normalization on an end to the war in Ukraine, or on Minsk playing a central role in softening the Kremlin’s terms for a settlement, is counterproductive to what the U.S. is trying to achieve with its opening to Belarus. Simply put, establishing this type of direct linkage neither improves Washington’s posture with Minsk nor benefits its negotiating position with Russia. Lukashenko does not have the leverage to pressure Moscow into diplomatic or battlefield concessions that it is otherwise not inclined to make. Indeed, the leverage mostly runs the other way. Belarus is much too economically, politically, and militarily dependent on Russia to play a driving role in breaking the current diplomatic logjam between Moscow and Kyiv.

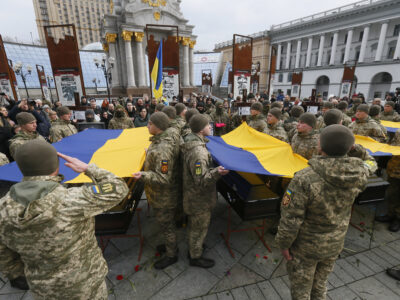

This is not to suggest that Minsk has no role to play in bringing the war closer to an end and supporting a durable settlement over the long haul. It would be constructive for President Lukashenko to publicly endorse, even if in broad brushstrokes, President Trump’s efforts to secure a negotiated settlement between Russia and Ukraine and to reaffirm Minsk’s availability as a back channel and platform for contacts between Russia and Ukraine. Subsequent rounds of formal Russia–Ukraine peace talks are unlikely to be held in Minsk, but there is an important technical-diplomatic niche to the peace process that Belarus is well-positioned to fill. This includes ongoing Belarusian efforts to facilitate exchanges of prisoners of war and bodies of fallen soldiers.34

The nonaggression provisions outlined above create the conditions necessary for much-needed confidence-building between Belarus and Ukraine, opening a space for future cooperation on regional deconfliction and border security. In the longer term, Belarus has a potentially significant humanitarian and economic role in supporting Ukraine’s postwar reconstruction through resumption of trade, energy cooperation, development, and joint investment in Ukraine’s manufacturing sector, opening logistics routes for access to the Baltics, and support for Ukrainian refugees.

Ukraine borders three non–NATO states — Russia, Moldova, and Belarus — and is on hostile footing with two of them. Russia–Ukraine ties have been ruptured by the invasion in ways that cannot be quickly or easily addressed, but Ukraine’s relationship with its Belarusian neighbor, if buttressed by a broader rapprochement between Minsk and the West, can be shifted to a positive track that not only benefits both countries but helps promote regional stability without demanding a greater commitment of U.S. or NATO resources.

Conclusion

The administration has outlined a bold vision of American retrenchment away from Europe to free up U.S. resources for other theaters, particularly the Indo–Pacific. The first and most conspicuous part of this approach is to promote a program of not just burden sharing but burden shifting, leading to the eventual reshoring of European defense capabilities. Yet the U.S. continues to maintain a constellation of interests and commitments in Europe, and it will prove impossible for it to extricate itself as Europe’s chief security provider over the long term if NATO’s eastern flank remains a perpetually volatile battleground between Russia and the West. Increased European deterrence therefore has to be accompanied by concrete steps, most of which can be taken only by the U.S., to stabilize the region with the aim of avoiding future security spirals. This requires adopting a fresh approach to the “in-between” post–Soviet countries — Moldova, Belarus, Armenia, and Georgia — that have not joined NATO. Rather than framing relations with these states as an exclusive choice between Euro–Atlantic integration and Russia, U.S. interests would be better served by building constructive relationships with these actors on their own terms, in ways that are mutually beneficial and do not saddle the U.S. with additional commitments in a region where vital American interests are not at stake. Nowhere is this opportunity more pronounced and readily available than with Belarus, which has long sought precisely that kind of flexible relationship.

Program

Entities

Citations

Andrew Higgins and Tomas Dapkus, “Trump Sends Envoy to Belarus, Courting Ties with Russia’s Close Ally,” New York Times, June 21, 2025, https://www.nytimes.com/2025/06/21/world/europe/trump-belarus-envoy-russia.html. ↩

Mark Episkopos, “Rethinking the U.S.–Belarus Relationship,” Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft,” May 13, 2024, https://quincyinst.org/research/rethinking-the-u-s-belarus-relationship/#. ↩

Neil MacFarquhar, “World Leaders Meet in Belarus to Negotiate Cease-Fire in Ukraine,” New York Times, Feb. 11, 2015, https://www.nytimes.com/2015/02/12/world/europe/meeting-of-world-leaders-in-belarus-aims-to-address-ukraine-conflict.html; “Belarus Says Won’t Recognise Georgia Regions Yet,” Reuters, Sept. 8, 2008, https://www.reuters.com/article/economy/belarus-says-wont-recognise-georgia-regions-yet-idUSL8687256/. ↩

Episkopos, “Rethinking the U.S.–Belarus Relationship.” ↩

Anna Maria Dyner, “The Border Crisis as an Example of Hybrid Warfare,” PISM, Feb. 2, 2022, https://www.pism.pl/publications/the-border-crisis-as-an-example-of-hybrid-warfare; Elena Giordano, “Lithuania Takes Belarus to The Hague for Weaponizing Migration,” Politico, May 20, 2025, https://www.politico.eu/article/belarus-lithuania-the-hague-smuggling-migrants-borders/. ↩

Mark Trevelyan, “Lukashenko Frees 15 More Prisoners on Eve of Belarus Election,” Reuters, Jan. 24, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/belarusian-leader-lukashenko-pardons-15-more-people-eve-election-2025-01-24/; Michele Kelemen and Charles Maynes, “Belarus Has Released 3 from Prison, Including an American and a Journalist,” NPR, Feb. 12, 2025, https://www.npr.org/2025/02/12/g-s1-48479/belarus-prisoners-released-american-white-house. ↩

Episkopos, “Rethinking the U.S.–Belarus Relationship.” ↩

Balázs Jarábik, “Is There a Chance for Re-Engagement between Belarus and the E.U.?,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, June 18, 2025, https://carnegieendowment.org/russia-eurasia/politika/2025/06/belarus-eu-relations?lang=en. The Belarusian “balcony” refers to Belarus’ geostrategic position as a buffer and military staging ground between Russia, Ukraine, and NATO’s eastern flank. The balcony can, and historically has been, used to threaten Russia or its Western neighbors depending on the regional geopolitical configuration. Although Moscow maintains escalation dominance and an asymmetry of interest, both Russia and the West have an interest in mitigating potential threats emanating from the Belarusian balcony. ↩

Episkopos, “Rethinking the U.S.–Belarus Relationship.” ↩

Yauheni Preiherman, “Can Belarus Survive without a Multi-Vector Foreign Policy?,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Jan. 21, 2021, https://carnegieendowment.org/posts/2020/11/can-belarus-survive-without-a-multi-vector-foreign-policy?lang=en. ↩

Anna J. Davis, “Belarus Cultivates Family-Style Relations with the People’s Republic of China,” Jamestown Foundation, June 13, 2025, https://jamestown.org/program/belarus-cultivates-family-style-relations-with-the-peoples-republic-of-china. ↩

Wang Qi and Bai Yunyi, “China, Belarus Maintain Close Exchanges at All Levels: FM on Lukashenko’s Visit,” Global Times, June 3, 2025, https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202506/1335359.shtml. ↩

Dara Massicot et al., “Cooperation and Dependence in Belarus–Russia Relations,” RAND, June 20, 2024, https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA2061-3.html. ↩

“Lukashenko: ‘I Want Normal Relations with the West on One Condition: Do Not Interfere in Our Garden,’” BelTA, Feb. 16, 2023, https://www.belta.by/president/view/lukashenko-ja-hochu-normalnyh-otnoshenij-s-zapadom-odno-uslovie-ne-lezt-v-nash-ogorod-550636-2023/. ↩

Frederik Pleitgen, Zahra Ullah, Claudia Otto, and Rob Picheta, “Belarus Claims It Won’t Send Troops to Ukraine Unless It Is Attacked, as Tensions Escalate at Border,” CNN, Feb. 16, 2023, https://www.cnn.com/2023/02/16/europe/belarus-ukraine-troops-russia-border-intl/index.html. ↩

Yauheni Preiherman, “Belarus Downsizes Zapad–2025 to Reduce Escalation Risks,” Jamestown Foundation, June 11, 2025, https://jamestown.org/program/belarus-downsizes-zapad-2025-to-reduce-escalation-risks/. ↩

Hélène Bienvenu, “Relations between Poland and Belarus Are as Tense as Ever,” Le Monde, March 6, 2023, https://www.lemonde.fr/en/international/article/2023/03/06/relations-between-poland-and-belarus-are-as-tense-as-ever_6018280_4.html#. ↩

Bob Deen, Barbara Roggeveen, and Wouter Zweers, “An Ever Closer Union? Ramifications of Further Integration between Belarus and Russia,” Clingendael, August 2021, https://www.clingendael.org/publication/ramifications-further-integration-between-belarus-and-russia. ↩

Заседание Совета Безопасности [Security Council Meeting],” Pravo, July 7, 2023, https://pravo.by/novosti/obshchestvenno-politicheskie-i-v-oblasti-prava/2025/july/89359/. ↩

“Belarus, USA Keen to Exchange Experience in Combating Illegal Drug Trade,” March 2, 2020, BelTA, https://eng.belta.by/society/view/belarus-usa-keen-to-exchange-experience-in-combating-illegal-drug-trade-128645-2020/; “Belarus and the United States,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Belarus, https://mfa.gov.by/en/bilateral/america/usa_canada/usa/. ↩

“Relations with Belarus,” NATO, Aug. 28, 2024, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/topics_49119.htm. ↩

“Number of Electric Cars in Belarus Doubles in 2024,” BelTA, Dec. 19, 2024, https://eng.belta.by/economics/view/number-of-electric-cars-in-belarus-doubles-in-2024-164072-2024/; “BelGee Launches Production of Electric Cars,” BelTA, May 20, 2025, https://eng.belta.by/economics/view/belgee-launches-production-of-electric-cars-168166-2025/. ↩

Emmet White, “Chevrolet Is Axing the Blazer EV Lineup’s Range Champ, the Rear-Wheel-Drive RS,” Road & Track, June 10, 2025, https://www.roadandtrack.com/news/a65022848/chevrolet-discontinues-rear-wheel-drive-blazer-ev/; George Barta, “2025 Cadillac Optiq Production Now Under Way,” GM Authority, Oct. 14, 2024, https://gmauthority.com/blog/2024/10/2025-cadillac-optiq-production-now-under-way/. ↩

“Belarus’ Potash Fertilizer Exports Reach Pre-Sanction Level — Lukashenko,” Interfax, May 23, 2025, https://interfax.com/newsroom/top-stories/111615/. ↩

Gleb Stolyarov, Filipp Lebedev, and Alexander Marrow, “Exclusive: Sanctions-Hit Belarus Looks to Gambia to Boost Its Depleted Air Fleet,” Reuters, March 26, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/business/aerospace-defense/sanctions-hit-belarus-looks-gambia-boost-depleted-fleet-2025-03-26/. ↩

“In Riyadh, President Trump Charts the Course for a Prosperous Future in the Middle East,” The White House, May 13, 2025, https://www.whitehouse.gov/articles/2025/05/in-riyadh-president-trump-charts-the-course-for-a-prosperous-future-in-the-middle-east/. ↩

“Belarus: E.U. Suspends Restrictive Measures against Most Persons and All Entities Currently Targeted,” Council of the E.U., Oct. 30, 2015, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2015/10/29/belarus/. ↩

Andrius Sytas and Mark Trevelyan, “Lukashenko Frees Husband of Exiled Belarus Opposition Leader in U.S.–Brokered Deal,” Reuters, June 21, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/belarus-opposition-leader-tsikhanouski-freed-jail-his-wife-says-2025-06-21/. ↩

Kacper Pempel and Maria Kiselyova, “‘Go Through. Go,’ Lukashenko Tells Migrants at Polish Border,” Reuters, Nov. 26, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/lukashenko-tells-migrants-belarus-poland-border-he-wont-make-them-go-home-2021-11-26/. ↩

“Poland Needs to Respect Its International Human Rights Obligations on the Belarusian Border, Says Commissioner O’Flaherty,” Council of Europe, Sept. 23, 2024, https://www.coe.int/en/web/portal/-/poland-needs-to-respect-its-international-human-rights-obligations-on-the-belarusian-border-says-commissioner-o-flaherty; “Poland: Brutal Pushbacks at Belarus Border,” Human Rights Watch, Dec. 10, 2024, https://www.hrw.org/news/2024/12/10/poland-brutal-pushbacks-belarus-border. ↩

Vadim Kushnikov, “Belarusian Helicopters Breach Polish Airspace,” Militarnyi, Aug. 1, 2023, https://militarnyi.com/en/news/belarusian-helicopters-breach-polish-airspace/; “Poland Neutralises Sabotage Group Linked to Belarus and Russia,” Reuters, Sept. 9, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/poland-neutralises-sabotage-group-linked-belarus-russia-2024-09-09/. ↩

George Barros, “Belarus Warning Update: Lukashenko Accuses Poland of Preparing Catholic Sectarian Subversion,” Institute for the Study of War, Nov. 2, 2020, https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/belarus-warning-update-lukashenko-accuses-poland-preparing-catholic-sectarian. ↩

“Poland Says Entry of Trucks from Belarus Slowed by Sanctions,” Reuters, July 11, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/poland-says-entry-trucks-belarus-slowed-by-sanctions-2024-07-10. ↩

“Russia and Ukraine Swap More POWs in Second Exchange in Two Days,” Reuters, June 20, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/russia-ukraine-swap-more-pows-second-exchange-two-days-2025-06-20/; Paul Adams and Laura Gozzi, “Families of Missing Ukrainians Gather as Prisoner Exchange Begins,” BBC, June 9, 2025, https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c20q4wgx5xxo; “Chinese-Built Belarusian Large Agro-Industrial Complex Put into Operation,” National Development and Reform Commission, Nov. 22, 2022, https://en.ndrc.gov.cn/netcoo/goingout/202211/t20221122_1343217.html. ↩