Keys to Developing a More Efficient, Effective Defense at Lower Cost

This brief was co-published by the Stimson Center and Taxpayers for Common Sense.

Overview

Introduction

The Trump administration’s stated commitment to reducing waste and inefficiency across the federal government offers important opportunities for policymakers to address excessive Pentagon spending.

Not only will smart, targeted Pentagon budget cuts save tens of billions of dollars, but they will also strengthen national security. By eliminating dysfunctional weapon systems and unnecessary missions, policymakers will enable the Pentagon to focus on the most urgent national security challenges. The Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) may facilitate more intentional, effective national security spending by promoting the action items below.

They fall into four key categories:

- Cancelling or reducing spending on dysfunctional or unnecessary weapons systems.

- Making process changes that will encourage greater spending discipline.

- Reducing bureaucracy, including both government personnel and the department’s hundreds of thousands of private contract employees.

- Cutting excess basing infrastructure.

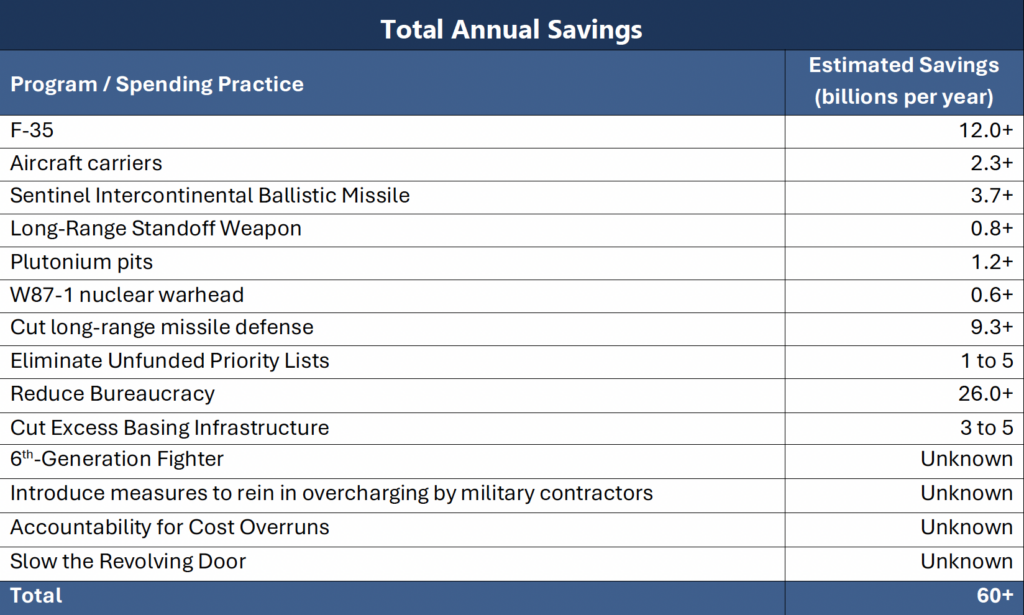

Conservatively, total annual savings from the changes outlined below would be at least $60 billion.1However, this is not a comprehensive list. Policymakers could achieve billions of dollars in additional savings by aligning military force structure with a more realistic grand strategy of restraint. Short of such a shift, the proposals below would advance a leaner and more effective Pentagon.

Rethinking Weapons Systems

F-35 combat aircraft – Estimated Savings: $12 billion or more per year.

In the mid-1990s, the Air Force touted the F-35 Lightning II program (then known as the Joint Strike Fighter) as a new, revolutionary approach to procurement that would create a next-generation system at a price considerably lower than its predecessor.

Yet, twenty-three years after the beginning of the program, the F-35 is plagued with cost and performance problems. It’s now projected to cost taxpayers more than $2 trillion over the course of its lifecycle, and its full mission capable rate, the percentage of time it can fly and perform all of its missions, is about 30 percent.2

The original sin of the F-35 program was the decision to give its variants widely different missions, from winning aerial dogfights, to dropping bombs, to providing close air support to troops on the ground, to landing on aircraft carriers, to conducting vertical/short takeoffs and landings (V/STOL). As a result, the F-35 does all of those things, but it does none of them particularly well. Add to this the fact that the F-35 program is the most expensive weapons program in the history of the Pentagon and calling it a bad bargain for the armed forces and the taxpayer is a vast understatement.

Preventing further wasteful investments in this underperforming platform would require policymakers to halt the F-35 program at current levels, at an estimated savings of over $12 billion per year.3 A combination of upgraded versions of the F-16 and F/A-18 and unpiloted aircraft can help fulfill the F-35’s missions at a lower cost to taxpayers.4

Sixth-Generation Fighters – Savings: Unknown

The Air Force and Navy are both in the relatively early stages of developing sixth-generation fighter aircraft, but those plans have come under scrutiny following the revelation that each fighter could cost roughly three times the cost of an F-35. Over the summer, the Air Force paused its program and launched a review due to both fiscal considerations and to ensure “that we had the right concept,” according to Air Force Secretary Frank Kendall.5 More recently, Air Force officials announced they would defer a final decision on the future of the program so that the Trump administration could weigh in.6

First and foremost, for both the Air Force and Navy programs, the Trump administration should examine the strategic need for a sixth-generation fighter and determine whether other capabilities like long-range fires, attritable drones, and ground-based air defenses can accomplish the same strategic goals at a lower cost.

If the administration determines that a sixth-generation fighter is necessary, then it must decide whether the fighter should be crewed or uncrewed. An uncrewed fighter would likely cost far less. It could also reduce risk to pilots and allow for maneuvering capabilities that would not be possible for a crewed fighter. But an uncrewed fighter would also come with risks, from greater vulnerability to cyber threats to ethical and technical concerns associated with autonomous weapons.

Another central question is how to avoid the mistakes of the F-35. Requiring design completion prior to production (“fly before you buy”) would help avoid the types of cost overruns, schedule delays, and performance issues associated with the F-35. Limiting the scope of a next-generation fighter’s missions could also help reduce costs and improve performance.

Meaningful estimates of the savings yielded by canceling the sixth-generation fighter program cannot be made given that it is so early in the program. However, there are indications that a crewed sixth-generation fighter may be triple the cost of an F-35. Policymakers could likely save tens of billions of dollars or more by ending the program.

Aircraft Carriers – Estimated Savings: $2.3 billion or more per year.

Modern aircraft carriers are enormously expensive and highly vulnerable to enemy attack in the form of modern, high speed missile systems. Their lasting power is a testament to pork barrel politics, not their military value. Indeed, aircraft carriers’ main selling point on Capitol Hill is the jobs they create in states like Virginia – home to Newport News Shipbuilding, a subsidiary of Huntington Ingalls and a major employer and economic contributor to the state. Policymakers, however, would do well to evaluate major acquisition programs by their strategic and military value, rather than their potential economic impacts. As Rep. Ken Calvert (R-CA) pointedly asked in recent comments on the waning value of aircraft carriers, “Will aircraft carriers be survivable in modern warfare when the Chinese right now have 1,200 operational hypersonic missiles that can be clustered at Mach 6, Mach 7?”7 The purpose of Pentagon spending is to build a military force capable of protecting the United States and its allies against attack, not to stimulate the economy. Further, Pentagon spending is a relatively poor jobs-creator.8

Given the increasing vulnerability of aircraft carriers, the United States could stop buying carriers like the Gerald R. Ford class carrier, which cost an astonishing $13 billion each at the time of its procurement in 2007 – over $20 billion each in 2024 dollars.9 By ceasing continued procurement of these aircraft carriers, the Pentagon can save about $2.3 billion in fiscal year 2025.10

The Sentinel ICBM – Estimated Savings: $3.7 billion or more per year; $310 billion total.

Replacing the land-based leg of the nuclear triad with a new generation of intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) is both costly and unnecessary. While ICBMs were once the most powerful and accurate weapons in our nuclear arsenal, advances in submarines and bombers have rendered them redundant, while advances in hypersonic technology have increased their vulnerability. Not only are ICBMs obsolete, they are also dangerous. As former Secretary of Defense William Perry and numerous other experts have noted, a president would only have a matter of minutes to decide whether or not to launch America’s ICBMs upon warning of an attack, greatly increasing the danger of an accidental nuclear war based on a false alarm.

The Sentinel is also hugely expensive. Last year, a 37 percent cost spike triggered a critical breach of the Nunn-McCurdy Act, forcing the Pentagon to review the program. The review concluded that a restructured program would in fact cost 81 percent more than anticipated.11 By continuing the program, the Pentagon is doubling down on a costly and antiquated approach to nuclear deterrence. The department can change course by canceling the program and working to retire the Minuteman III at the earliest opportunity. Should the program move forward, alternative approaches like reducing the number of deployed ICBMs or fielding a mix of Sentinel and Minuteman III ICBMs could save taxpayers billions of dollars.

Total acquisition costs for the Sentinel program in FY 2025 were $3.7 billion, which offers a highly conservative estimate for annual savings from cutting the program.12Accounting for the latest cost spike, cutting the program would save taxpayers an estimated $310 billion, given its lifecycle costs.13

The W87-1 Nuclear Warhead – Estimated Savings: $687 million or more per year; $15 billion total.

In keeping with our recommendation to cut the Sentinel ICBM, we recommend cutting the accompanying nuclear warhead, the W87-1. Cutting this warhead would save taxpayers an estimated $687 million per year, and up to $15.6 billion over the program’s lifecycle.14

Long-Range Standoff Weapon (LRSO) – Estimated Savings: $834 million or more per year.

The Long-Range Standoff Weapon (LRSO) is a nuclear-armed cruise missile designed to be launched by a long-range bomber. As former secretary of defense William Perry and former assistant secretary of defense Andy Weber have noted, “[b]ecause they can be launched without warning and come in both nuclear and conventional variants, cruise missiles are a uniquely destabilizing type of weapon.”15 Essentially, an adversary might mistake a conventionally-armed cruise missile for a nuclear-armed one, unintentionally sparking a potential nuclear confrontation. Former British defense secretary Philip Hammond underscored the risks when he noted that “a cruise-based deterrent would carry significant risk of miscalculation and unintended escalation.”16 Cancelling the program would save taxpayers an estimated $834 million per year.17

“Pit” Production Plant at the Savannah River Plant – Estimated Savings: $1.2 billion or more per year; $25 billion total.

Plutonium pits are essentially triggers that set off the chain of events leading to the explosion of a nuclear bomb. The NNSA is developing the capability to produce more pits via a major project at the Savannah River Plant in South Carolina. Pits may be needed to swap into nuclear warheads that are no longer “reliable’ – in other words, might not explode if launched. But the NNSA has more than enough pits in its current stockpile, so the Savannah River Project is unnecessary and enormously costly. Cancelling the Savannah River Plant would save taxpayers an estimated $1.2 billion or more per year, or $25 billion in total.18

Cut long-range missile defense – Estimated Savings: $9.3 billion or more per year.

The United States currently spends over $28 billion per year on what the Pentagon calls “missile defeat and defense,” which includes short-, medium- and long-range systems.19 Since the 1950s, the United States has wasted over $400 billion on overly ambitious, unworkable systems that cannot succeed in a realistic environment.20Indeed, the American Physical Society found in 2022 that no “system thus far developed has been shown to be effective against realistic ICBM threats” to the United States.21In the past, the Pentagon has concealed operational testing and evaluation reports on missile defense systems.22Testing is expensive, difficult, and time-intensive. As a result, there is political incentive to avoid testing missile defense programs in challenging environments – or to neglect testing altogether. Cutting investments in missile defense and defeat by one-third from current levels would save taxpayers $9.3 billion per year while still allowing for significant investments in systems that have shown some capability, like medium range interceptors.

Smarter Purchasing and Greater Budget Discipline

Introduce measures to rein in overcharging by military contractors – Savings: Unknown

Military contractors have overcharged the Pentagon for decades, in one recent case, by as much as 3,800 percent above the fair and reasonable price for a spare part.23 Still, the Pentagon lacks the leverage it needs to negotiate fair prices on military contracts. One key reform would be to strengthen requirements for military contractors to provide current, complete, and accurate cost and pricing data to Pentagon contract officers. Without this information, they risk flying blind in negotiations over the fair price of any given item.

Accountability for Cost Overruns – Savings: Unknown

The Nunn-McCurdy process mandates congressional notification and a review of major Pentagon programs experiencing critical cost growth of 25 percent or more. Currently, when a program experiences critical cost growth, the Pentagon is solely responsible for reviewing the offending program and certifying it to move forward. Policymakers can strengthen the process by empowering an independent commission to review programs experiencing critical cost growth to ensure unbiased reviews, and by requiring congressional approval of recertified programs. They can also expand the scope of Nunn-McCurdy to include cost growth in nuclear weapons programs managed by the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA), which are not currently covered by the Nunn-McCurdy Act. Savings from these changes to the Nunn-McCurdy process are difficult to estimate, but greater accountability measures for programs experiencing major cost growth would likely save taxpayers billions of dollars in the long run by creating disincentives for both the Pentagon and its contractors to underestimate costs.

Slow the Revolving Door – Savings: Unknown

The arms industry benefits greatly from the employment of former government officials as lobbyists. On average, the weapons industry has 800 lobbyists, the majority of whom passed through the revolving door.24 Policy makers may slow the revolving door and decrease undue corporate influence in defense policy by increasing the cooling off period for government officials leaving the government to enter the arms industry. Stronger recusal requirements would prevent Pentagon officials from favoring their former employers in the arms industry. A more accurate definition of a lobbyist would also include board members, company executives, ex-government officials and people who work in the venture capital field whose primary focus is funding defense startups. This proposal is similar to elements of the Department of Defense Ethics and Anti-Corruption Act of 2023, introduced by Sen. Elizabeth Warren.

Eliminate Unfunded Priorities Lists – Estimated Savings: $1 to 5 billion per year.

Since 2017, Congress has required the military service branches and combatant commands to submit “unfunded priority lists,” extrabudgetary wish lists of items the Pentagon did not include in its budget request. This circumvention of the Commander-in-Chief and the Pentagon’s civilian leadership fuels wasteful spending and can come at the expense of real priorities included in the President’s budget.25 Former Secretary of Defense Robert Gates strongly discouraged the use of these lists, while Former Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin explicitly supported repealing the statutory requirement for them.26

In Fiscal Year 2025, wish list requests exceeded $30 billion, over $5 billion of which made it into the House and Senate Defense Appropriations Bills.27 Some lawmakers are also pushing to expand these requirements to other agencies like the State Department and the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), which would further entrench bad budgetary practice.28

The President can urge Congress to repeal the requirements for these wish lists, and can also encourage military service leaders and combatant commanders to work within the normal budget process and submit empty lists to fulfil the congressional requirement, as some combatant commands already have.29 The United States needs a holistic approach to budgeting for national security, not the free-for-all generated by unfunded priority lists.

Cutting Bureaucracy – Estimated Savings: $26 billion per year by cutting spending in this category by 15 percent.

Service contracts account for about half of the Pentagon’s purchases. The majority of these contracts are for professional services like administrative or technical support, but service contracts also include IT support, equipment installation and maintenance, and medical services. Researchers project significant savings by trimming the department’s roster of over 500,000 private contractors, many of whom do jobs that are either redundant or can be done better or more cheaply by government employees. In one 2015 study, the Defense Business Board estimated $125 billion in potential savings, in part by significantly reducing service contracting.30 And an analysis by the Project On Government Oversight estimates that cutting spending on private contractors by 15 percent would save up to $26 billion per year.31

Cutting Excess Basing Infrastructure – Estimated Savings: $3 – $5 billion per year.

The Pentagon has said it has 19 percent excess basing capacity, meaning 19 percent more basing infrastructure than is necessary for national security.32 Addressing this excess capacity through targeted closures and realignments of U.S. military bases both domestically and abroad would save taxpayers billions of dollars and strengthen national security by focusing infrastructure investments where they are most needed.

The Base Realignment and Closure (BRAC) process has proven to be an effective means of addressing excess basing capacity in a fair way that takes into account the impacts closures and realignments can have on nearby communities. While base closures and realignments do come with some upfront costs, the last BRAC process, initiated under the Bush administration in 2005, led to annual taxpayer savings of about $3.8 billion.33 Twenty years later, another BRAC process is long overdue.

Conclusion

Contrary to popular belief in Washington, national security and fiscal discipline are not mutually exclusive. In fact, they are inextricably linked. Budgeting for U.S. national security needs today and into the future requires that policymakers tackle wasteful spending and inefficiencies across the board, and with the Pentagon budget closing in on $1 trillion per year, the United States cannot afford to ignore it. Thankfully, tackling Pentagon programs and practices that do not offer a good return on investment will not only save taxpayers billions of dollars—it will also help illuminate and sustain the U.S.’ greatest national security priorities.

Organizations

The Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft believes that efforts to maintain unilateral U.S. dominance around the world through coercive force are neither possible nor desirable. A transpartisan, action-oriented research institution, QI promotes ideas that move U.S. foreign policy away from endless war and towards vigorous diplomacy in pursuit of international peace.

The Stimson Center promotes international security and shared prosperity through applied research and independent analysis, global engagement, and policy innovation. For three decades, Stimson has been a leading voice on urgent global issues. Founded in the twilight years of the Cold War, the Stimson Center pioneered practical new steps toward stability and security in an uncertain world. Today, as changes in power and technology usher in a challenging new era, Stimson is at the forefront: Engaging new voices, generating innovative ideas and analysis, and building solutions to promote international security, prosperity, and justice.

Taxpayers for Common Sense is a non-partisan budget watchdog serving as an independent voice for American taxpayers. The organization’s mission is to ensure that the federal government spends taxpayer dollars responsibly and operates within its means.

Program

Entities

Citations

Most of the annual savings estimates in this document are based on acquisition costs for Fiscal Year 2025, which offer a rough and likely conservative estimate of yearly costs moving forward. ↩“The F-35 Will Now Exceed $2 Trillion As the Military Plans to Fly It Less.” United States Government Accountability Office. May 16, 2024. https://www.gao.gov/blog/f-35-will-now-exceed-2-trillion-military-plans-fly-it-less; “F-35 Aircraft: DOD and the Military Services Need to Reassess the Future Sustainment Strategy.” United States Government Accountability Office. Sep. 21, 2023. https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-23-105341.pdf ↩

“Program Acquisition Cost by Weapon System.” Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller)/Chief Financial Officer. March 2024. p. xv. https://comptroller.defense.gov/Portals/45/Documents/defbudget/FY2025/FY2025_Weapons.pdf ↩

“The Unaffordable F-35: Budget History and Alternatives.” Taxpayers for Common Sense. April 2014. https://www.taxpayer.net/wp-content/uploads/ported/images/Alternatives%20to%20the%20F35(1).pdf ↩

Marrow, Michael, and Valerie Insinna. “NGAD EXCLUSIVE: Air Force secretary cracks door for unmanned next-gen fighter.” Breaking Defense. July 22, 2024. https://breakingdefense.com/2024/07/ngad-redesign-air-force-secretary-cracks-door-forunmanned-option-exclusive/ ↩

Losey, Stephen. “Air Force defers NGAD decision to Trump administration.” Defense News. Dec. 5, 2024. https://www.defensenews.com/breaking-news/2024/12/05/air-force-defers-ngad-decision-to-trump-administration/ ↩

Bertuca, Tony. “Calvert calls for spending reviews that could cut aircraft carriers and tanks.” Inside Defense. Jan. 14, 2025. https://insidedefense.com/daily-news/calvert-calls-spending-reviews-could-cut-aircraft-carriers-and-tanks ↩

“Study says domestic, not military spending, fuels job growth.” Brown University. May 25, 2017. https://www.brown.edu/news/2017-05-25/jobscow ↩

“Navy Ford (CVN-78) Class Aircraft Carrier Program: Background and Issues for Congress.” United States Government Accountability Office. Dec. 13, 2024, https://sgp.fas.org/crs/weapons/RS20643.pdf#page=8. ↩

“Program Acquisition Cost by Weapon System.” Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller)/Chief Financial Officer. March 2024. p. xvi. https://comptroller.defense.gov/Portals/45/Documents/defbudget/FY2025/FY2025_Weapons.pdf ↩

“DOD Press Briefing Announcing Sentinel ICBM Nunn-McCurdy Decision.” U.S. Department of Defense. July 8, 2024. https://www.defense.gov/News/Transcripts/Transcript/Article/3830251/dod-press-briefing-announcing-sentinel-icbm-nunn-mccurdy-decision/ ↩

“Program Acquisition Cost by Weapon System.” Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller)/Chief Financial Officer. March 2024. p. xvi. https://comptroller.defense.gov/Portals/45/Documents/defbudget/FY2025/FY2025_Weapons.pdf ↩

“Ripe for Rescission: A Cost-Benefit Analysis of U.S. ICBMs.” Taxpayers for Common Sense. May 30, 2024.https://www.taxpayer.net/national-security/ripe-for-rescission-a-cost-benefit-analysis-of-u-s-icbms/ ↩

“NNSA Should Further Develop Cost, Schedule, and Risk Information for the W87-1 Warhead Program.” United States Government Accountability Office. September 2020. https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-20-703.pdf ↩

Perry, William, and Andy Weber. “Mr. President, Kill the New Cruise Missile.” Washington Post. Oct. 15, 2015. https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/mr-president-kill-the-new-cruise-missile/2015/10/15/e3e2807c-6ecd-11e5-9bfe-e59f5e244f92_story.html ↩

Ibid. ↩

“Program Acquisition Cost by Weapon System.” Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller)/Chief Financial Officer. March 2024. p. xvi. https://comptroller.defense.gov/Portals/45/Documents/defbudget/FY2025/FY2025_Weapons.pdf ↩

Leon, Dan. “NNSA seeks $1B boost for fiscal year 2025; Savannah River pit estimate soars.” Exchange Monitor. March 15, 2024. https://www.lasg.org/press/2024/ExchangeMonitor-BudgetBoost_15Mar2024.html ↩

“Defense Budget Overview: United States Department of Defense Fiscal Year 2025 Budget Request.” Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller)/Chief Financial Officer. March 2024. Revised April 4, 2024. https://comptroller.defense.gov/Portals/45/Documents/defbudget/FY2025/FY2025_Budget_Request_Overview_Book.pdf ↩

“Missile Defense: National missile defense: defense theology with unproven technology.” Center for Arms Control and Non-Proliferation. Accessed Jan. 8, 2025. https://armscontrolcenter.org/issues/missile-defense/. ↩

Hitchens, Theresa. “No US missile defense system proven capable against ‘realistic’ ICBM threats: Study.” Breaking Defense. Feb. 22, 2022. https://breakingdefense.com/2022/02/no-us-missile-defense-system-proven-capable-against-realistic-icbm-threats-study/ ↩

Lewis, George N. and Lisbeth Gronlund. “Debunking the Missile Defense Agency’s ‘Endgame Success’ Argument.” Arms Control Association. December 2002. https://www.armscontrol.org/act/2002-12/debunking-missile-defense-agencys-endgame-success-argument ↩

“Audit of the Business Model for TransDigm Group Inc. and Its Impact on Department of Defense Spare Parts Pricing.” Inspector General, U.S. Department of Defense. Dec. 31, 2021. p. 27. https://media.defense.gov/2021/Dec/27/2002914678/-1/-1/1/DODIG-2022-043%20508.PDF#page=35 ↩

“Political Footprint of the Military Industry.” Taxpayers for Common Sense. October 2024. https://www.taxpayer.net/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/Oct-2024-Political-Footprint-of-the-Military-Industry.pdf ↩

Murphy, Gabe. “Pentagon Budgeting Shouldn’t Look Like This.” The Hill. June 1, 2024. https://thehill.com/opinion/congress-blog/4697854-pentagon-budgeting-shouldnt-look-like-this/ ↩

Donnelly, John. “Pentagon comes out against law requiring military wish lists.” Roll Call. March 28, 2023. https://rollcall.com/2023/03/28/pentagon-comes-out-against-law-requiring-military-wish-lists/ ↩“Unfunded Priorities Lists for Fiscal Year 2025.” Taxpayers for Common Sense. March 27, 2024. https://www.taxpayer.net/national-security/unfunded-priorities-lists-for-fiscal-year-2025/; “Congressional Pentagon Budget Increases Up from Last Year.” Taxpayers for Common Sense. Sep. 12, 2024. https://www.taxpayer.net/national-security/congressional-pentagon-budget-increases-up-from-last-year/ ↩

“Kaine & Young Introduce Bill to Empower State Department and USAID to Counter People’s Republic of China, Other Threats.” Tim Kaine, United States Senator from Virgina. July 31, 2024. https://www.kaine.senate.gov/press-releases/kaine-and-young-introduce-bill-to-empower-state-department-and-usaid-to-counter-peoples-republic-of-china-other-threats ↩

Bertuca, Tony. “STRATCOM sends empty UPL to Congress.” Inside Defense. April 11, 2024. https://insidedefense.com/daily-news/stratcom-sends-empty-upl-congress ↩

“Transforming DoD’s Core Business Processes for Revolutionary Change.” Defense Business Board. Jan. 22, 2015. https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/AD1001666.pdf#page=3 ↩

“Spending Less, Spending Smarter: Opportunities to Reduce Excessive Pentagon Spending.” Project on Government Oversight. May 2019. https://www.citizen.org/wp-content/uploads/Defense-Savings-Options_20190515.pdf ↩

“Department of Defense Infrastructure Capacity.” Department of Defense. October 2017. https://federalnewsnetwork.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/101717_DoD_BRAC_Analysis.pdf ↩

“Military Base Realignments and Closures: Updated Costs and Savings Estimates from BRAC 2005.” United States Government Accountability Office. June 29, 2012. https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-12-709r.pdf ↩