Restraint and Diplomacy in Arctic Policy: Cooperation Amid U.S.-Russia-China Tensions

Executive Summary

In recent years, the Arctic has become the site of both great-power cooperation and competition. While the 2025 Alaska summit between Presidents Putin and Trump reflected a thaw in U.S.–Russia relations, U.S. interest in acquiring Greenland has cast doubt on continued U.S. cooperation with both Russia and China in the region. This brief details how a combination of restraint and proactive diplomacy in the Arctic — built upon shared interests and a recognition of competitive coexistence — will best serve the United States.

The second Trump administration has called for American Arctic dominance, viewing the region as an energy source and as an opportunity to monopolize resources and to establish its Western Hemisphere force posture. Russia views the Arctic through a similar lens of resources and sovereignty, as it ramps up its military presence while intensifying efforts to extract natural resources. China’s influence in the region has steadily increased, as it collaborates with Russia, while advancing scientific research, sustainable development, and multilateral climate cooperation.

The United States has come to see increasing Russia–China collaboration in the Arctic as a threat to U.S. national interests. But rather than responding to this deepening relationship through unilateralism, the U.S. should recognize that competitive coexistence and trilateral cooperation are more beneficial. This approach avoids zero-sum confrontation and minimizes accidental escalation while maintaining U.S. force projection, maximizing resource extraction, and promoting scientific collaboration. Toward this end, this brief recommends that the Trump administration:

- Establish trilateral maritime safety and search-and-rescue, SAR, operations, a system that exchanges real-time information, conducts joint training exercises, and invests in port and coast guard infrastructure. Such cooperation would lower shipping costs, improve safety, and encourage economic development — goals shared by the United States, Russia, and China.

- Institutionalize direct, reliable U.S.–Russia–China communication channels, including a dedicated Arctic hotline for incident reporting and a security digital platform for real-time vessel tracking. Such transparency minimizes the chances of miscalculation, particularly with nuclear assets in the region.

- Revitalize the Arctic Council to enable communication among the three major powers, the eight Arctic states, and Indigenous representatives.

- Initiate a trilateral arms control framework, using reductions in Arctic military exercises as a springboard for broader arms control and security arrangements.

Introduction

The Arctic has emerged as a critical region in international politics. Recent diplomatic events demonstrate the region’s growing importance. The 2025 Alaska summit between President Trump and Russian President Vladimir Putin exemplified renewed diplomacy and the potential for Arctic issues to play a role in the stabilization of U.S.–Russia relations.1The emerging Ukraine peace process and the February 2025 meeting between Secretary of State Marco Rubio and Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov in Saudi Arabia included Arctic cooperation as goals.2The region’s strategic value has increasingly become linked to wider security and diplomatic efforts.

However, the Arctic’s perceived role as a bastion of cooperation has not been immune to disruption. President Trump’s threats against Greenland — first issued in 2025 and again early this year — triggered an international crisis after Trump refused to rule out the use of military force to annex Greenland and threatened punitive tariffs on eight European countries unless Denmark ceded the territory. Trump reversed his position at the 2026 World Economic Forum and announced he had reached a “framework of a future deal” on Greenland.3The crisis underscored how easily great-power posturing can destabilize a region long characterized by diplomatic restraint and multilateralism. Such rhetoric marks a significant departure from the Arctic’s history as a relatively peaceful zone of cooperation, even when Cold War rivalries ran high.

The Arctic Council, established in 1996, became a symbol of this “exceptionalism,” bringing together the eight Arctic states (Canada, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Russia, Sweden and the United States), Indigenous representatives, and observers to advance sustainable development and environmental stewardship. Although the council’s work was effectively put on hold since the start of the war in Ukraine in 2022, the legacy of pragmatic engagement endures, and the Arctic continues to offer opportunities for renewed diplomacy.4

Meanwhile, China’s expanding role adds complexity. Beijing has invested in Arctic shipping, expanded its scientific research, and deepened its security and economic cooperation with Russia. China’s Polar Silk Road initiative, which extends its Belt and Road ambitions into the Far North, aligns with Moscow’s efforts to commercialize Arctic shipping.5

These developments have triggered anxiety in Western capitals about the prospect of a China–Russia axis challenging the established order. They also present new avenues for trilateral engagement. If managed carefully, the interlinking interests of the U.S., Russia, and China could create a framework for meaningful cooperation.

This policy brief outlines an Arctic strategy rooted in restraint and proactive diplomacy. At its core, the U.S.–Russia–China “Arctic strategic triangle” defines the region’s dynamics: U.S.–Russia rivalry, China–Russia partnership, and U.S.–China competition all converge here, amplifying both the risks of confrontation and the incentives for collaboration.6In this context, building trust offers a rare chance to reduce the likelihood of conflict and promote stability.

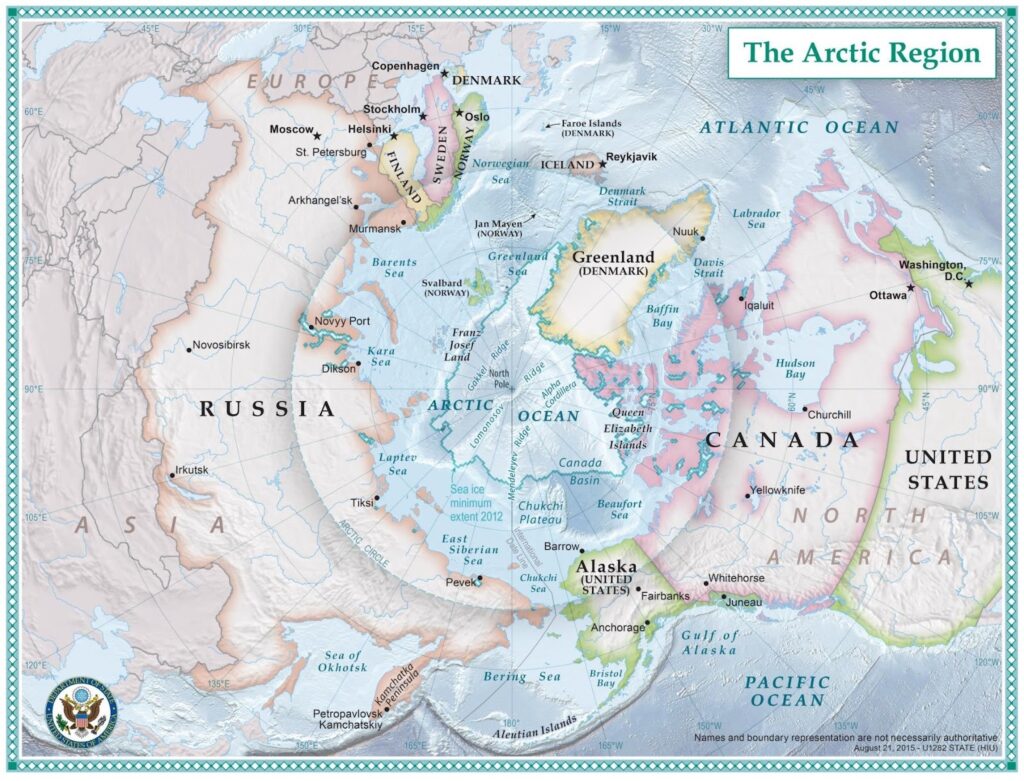

Figure 1. The Arctic Region

To move from rhetoric to results, all three powers should consider recalibrating their approaches. The U.S. should resist the temptation to frame the Arctic as a theater of military posturing and instead prioritize dialogue, confidence-building, and scientific research. Russia should moderate its assertiveness and demonstrate a willingness to compromise, especially on issues affecting maritime navigation. China should temper its rapid regional expansion and clarify its intentions to Arctic states and Indigenous communities. If each actor can exercise restraint and seek common ground, the Arctic could become a proving ground for great-power cooperation rather than yet another region of zero-sum competition.

The following sections present each state’s interests and narratives shaping their Arctic policies, pathways for trilateral cooperation, and the sources of mistrust. In general, these obstacles are longstanding security dilemmas and divergent interpretations of each other’s activities.

The brief concludes with policy recommendations, informed by the author’s on-the-ground engagement with American, Russian, and Chinese experts, diplomats, scientists, and businessmen. Security competition in the Arctic is not an imperative. Through creative diplomacy and mutual accommodation, the region can serve as a laboratory for peaceful coexistence and shared problem-solving.

U.S. Arctic priorities

America’s approach to the Arctic has evolved dramatically over decades, reflecting shifting threat perceptions and environmental imperatives. President Clinton’s 1994 Presidential Decision Directive 26 marked a turning point, articulating the first comprehensive U.S. policy for the Arctic and Antarctic.7

The directive emphasized environmental protection, sustainable development, and partnership with Russia, reflecting the optimism of the post–Cold War era. This cooperative ethos was institutionalized through U.S. leadership in co-founding the Arctic Council and supporting scientific collaboration on climate and ecology.

Under President Bush, the 2009 National Security Presidential Directive 66 maintained this cooperative tone but introduced security dimensions, focusing on missile defense, resources, and freedom of navigation.8

President Obama’s Arctic policy emphasized accelerating climate change. The 2013 National Strategy for the Arctic Region outlined goals to safeguard U.S. security, support the rights and well-being of Indigenous peoples, and deepen international cooperation.9

During President Trump’s first term, Arctic strategy was still oriented toward international cooperation but placed greater emphasis on the challenges posed by Russian and Chinese ambitions. The administration framed the region as a contested space, where the U.S. must compete to preserve its influence and prevent the emergence of rival blocs.10

President Biden’s 2022 National Strategy for the Arctic Region marked a return to earlier priorities, focusing on climate resilience, environmental justice, and Indigenous leadership.11At the Biden–Putin summit in Geneva in 2021, both presidents reaffirmed the Arctic as a zone of peaceful cooperation, even as bilateral relations strained elsewhere.12Indeed, the optimism of this period gave way to tension produced by the war in Ukraine.

The Department of Defense’s 2024 Arctic Strategy identified China–Russia collaboration as the main long-term threat to U.S. interests in the region.13President Trump’s second administration doubled down on calls for American Arctic dominance, sparking debates over the risks of militarization and the wisdom of abandoning restraint.

Trump’s controversial proposal to purchase Greenland from Denmark escalated into a series of direct threats early this year, with the president asserting that the island’s vast reserves of strategic minerals are too critical to be left under Danish control, particularly as both China and Russia ramp up their activities in the region. The Trump administration has escalated its pressure campaign against Denmark through threats of economic coercion and military force, though has seemingly backed off for the moment. This posture signals a shift toward a zero-sum mindset, one that prioritizes American control over energy and resources.

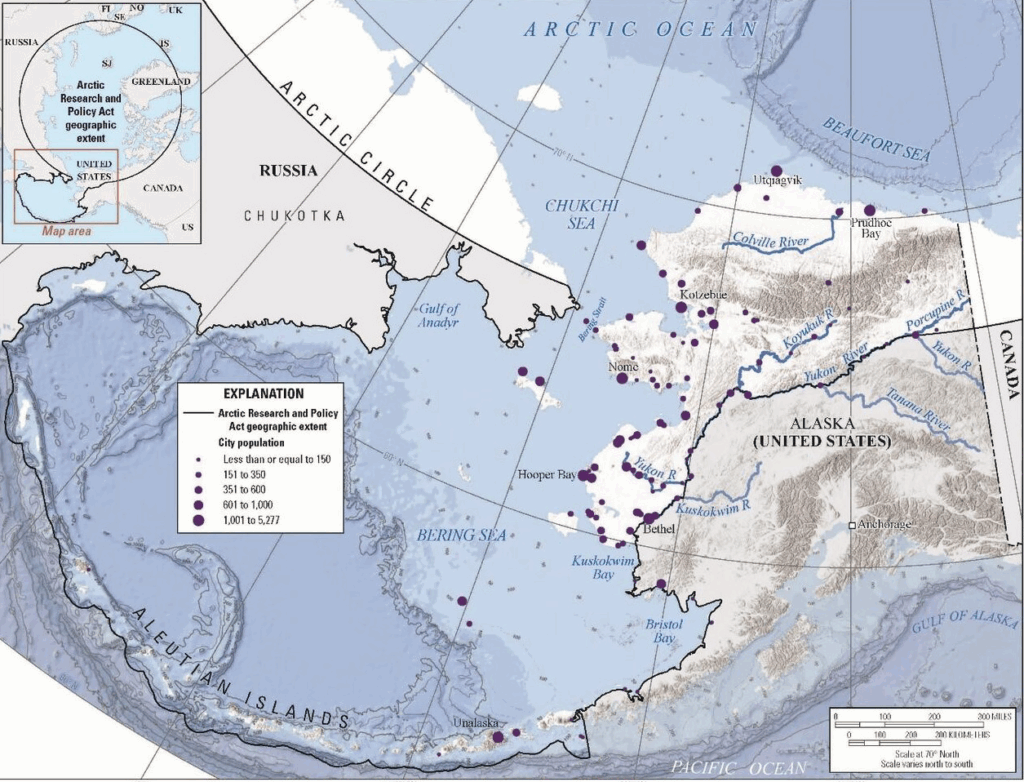

Figure 2: The Arctic Research and Policy Act Region — Bering Sea

This pivot was further exemplified by the administration’s decision to withdraw from the Paris Climate Accord, setting American energy production and economic growth above international commitments to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.14The move signaled a willingness to risk environmental fallout, particularly in the ecologically sensitive Arctic, for the sake of domestic interests.

Concurrently, Trump officials have explored unconventional collaborations, even considering leasing Russian nuclear-powered icebreakers to develop Alaska’s natural gas fields.15Resource competition is a central theme, with Trump expressing a strong interest in rare earth minerals in Russia and Greenland, aiming to reduce U.S. dependence on Chinese supply chains and block Chinese investment in Arctic mining.

The evolution in U.S. policy reflects the broader challenge facing all Arctic stakeholders: how to balance legitimate security concerns with the imperative to preserve the region as a space for dialogue and cooperation.

Looking forward, a more nuanced U.S. strategy might embrace the philosophy of “competitive coexistence.” This approach recognizes the inevitability of great-power rivalry but seeks to manage and contain it, leveraging opportunities for collaboration in areas of shared interest.16The 2021 National Intelligence Council’s Global Trends 2040 report sketches out such a scenario, envisioning a world where the U.S. and China sustain robust economic ties that stabilize relations despite simmering security disputes.17In the Arctic, this model could translate into selective partnerships with Russia and China on issues like sustainable development, scientific research, and maritime safety, leaving broader competition to other regions.

Russia’s Arctic priorities

Russia’s Arctic interests have evolved alongside broader shifts in its foreign policy, but certain priorities have persisted. Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev’s 1987 Murmansk speech was a foundational moment. His portrayal of the Arctic as a “zone of peace” advanced the myth of “Arctic exceptionalism” — the idea that the region should remain insulated from global geopolitical rivalries.18

This narrative set the tone for decades of Russian engagement, emphasizing mutually beneficial cooperation. Even today, Russia continues to support consensus-based Arctic collaboration, despite being effectively isolated from the other Arctic states, which are all NATO members as of 2024.

Dmitry Medvedev’s presidency, from 2008 to 2012, saw Russia embrace multilateralism and cooperative economic development. Russia’s 2008 Arctic strategy articulated a commitment to building cross-border partnerships, including with NATO states, and Medvedev frequently highlighted the importance of shared responsibilities and global norms.19

Putin’s return to the presidency in 2012, however, marked a recalibration. While Russia continued to participate in multilateral cooperation, it simultaneously ramped up military modernization, prioritized sovereignty over the Northern Sea Route, and intensified efforts to exploit the region’s resource wealth.

Despite facing escalating Western sanctions following the war in Ukraine, Moscow maintains a commitment to cooperation and argues for separating Arctic affairs from wider geopolitical disputes. Russia has remained a member of the Arctic Council, largely because it is on equal footing with the U.S. in an institution both countries co-founded. Russia continues to seek multifaceted cooperation with the U.S., underscoring the region’s unique status as an area of concurrent competition and cooperation.

Russia’s Arctic strategy is focused on using the Arctic as a strategic energy and natural resource base, managing the Northern Sea Route, supporting scientific research and cooperative projects, improving the lives of Arctic residents, and securing Russia’s economic interests and sovereignty in the region with a comprehensive military presence.20

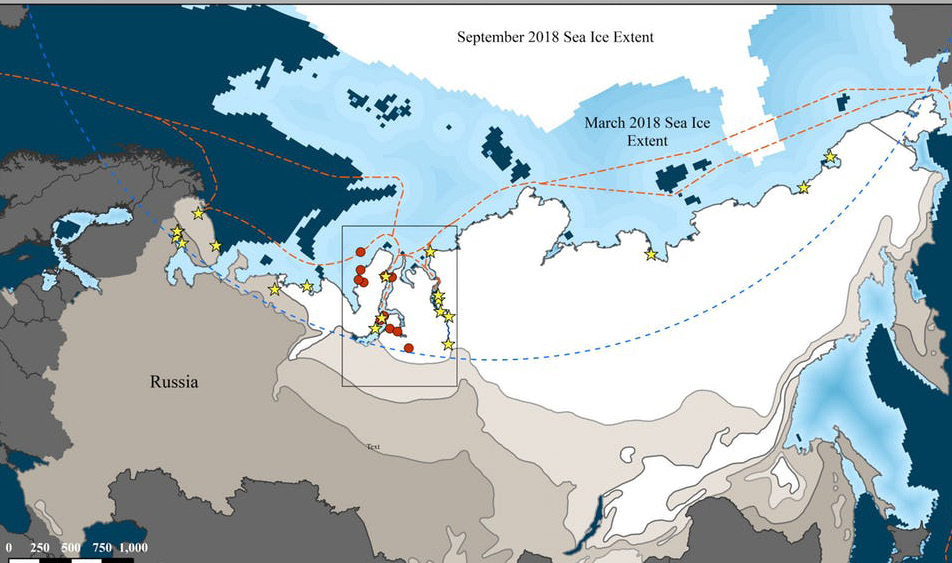

Figure 3: Changing Arctic Conditions

Russia’s priorities in the Arctic are rooted in economic necessity and historical memory. The region accounts for roughly 6 percent of Russia’s GDP and 10 percent of its exports.21Russia’s nuclear icebreaker fleet, the only one in the world, supports commercial development in the Arctic. Moreover, the trauma of military interventions through the Arctic, first by Allied forces during the Russian Civil War and later by Axis powers in World War II, has instilled a powerful sense of vulnerability and an imperative for robust security measures. Russia bases nuclear weapons and the Northern Fleet on the Kola Peninsula.

The political fallout from the Ukraine War has pushed Russia to adjust its partnerships, leaning more heavily on Chinese capital and technology for Arctic gas projects, shipping, and resource development, while remaining open to U.S. collaboration. This flexibility, balancing caution with engagement, presents opportunities for American diplomacy.

China’s Arctic priorities

China’s engagement with the Arctic has been methodical and calculated. In 2003, China established the Yellow River Station in Svalbard, Norway, marking its entry into Arctic research. Despite lacking any territory north of the Arctic Circle, China asserted its relevance by dubbing itself a “near–Arctic state” in its 2018 Arctic policy white paper.22This designation is rooted in a blend of pragmatic reasoning and strategic foresight.

Beijing argues that climate change in the Arctic has global repercussions, affecting Chinese agriculture, weather, and infrastructure. Moreover, the potential opening of shipping routes and access to natural resources carries global significance. By positioning itself as a stakeholder, China seeks to ensure it has a voice in shaping the region’s future.

China’s official Arctic policy outlines its intentions to deepen its understanding of Arctic climate systems, promote environmental protection, advocate for sustainable development, and pursue cooperation through established multilateral mechanisms. This approach serves multiple purposes. By emphasizing scientific research, China builds credibility with Arctic nations, showing that it is not just a resource-hungry outsider but a responsible participant concerned about global ecology. At the same time, Beijing’s commitment to sustainable development offers a diplomatic counterbalance to fears of unchecked exploitation.23

China’s Arctic aims are only achievable through partnership, most notably with Russia in liquefied natural gas projects and exploring the potential of the Northern Sea Route. This collaboration is mutually beneficial: Russia gains investment and technology while China secures energy supplies and develops alternative shipping lanes that could one day supplement or rival traditional routes like the Suez Canal.

Since obtaining observer status at the Arctic Council in 2013, China has steadily increased its participation in the region’s key multilateral forum. This seat at the table allows Beijing to build ties with Arctic states, monitor developments, and shape discussions on regional issues.

China’s Arctic ambitions are not fleeting. The inclusion of polar affairs in the 14th Five-Year Plan, the blueprint for China’s national development, shows that Arctic engagement is now woven into its broader foreign policy agenda.24This signals that China is prepared to make long-term investments in the region across research, commerce, and diplomacy.

A closer look at China’s diplomatic conduct in the Arctic reveals deep roots in its historical foreign policy doctrines. The Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence, first articulated by Premier Zhou Enlai in 1954 during Sino–Indian talks, can be considered a guiding framework. The principles emphasize mutual respect for sovereignty, non-aggression, non-interference in internal affairs, equality and mutual benefit, and peaceful coexistence.25

Analogous to the competitive or exceptionalist stances adopted by the U.S. and Russia, China’s foreign policy narrative presents itself as a cooperative actor. This narrative is designed to reassure others that China’s intentions are benign and that it seeks shared benefit rather than unilateral advantage.26

China is gradually increasing its influence in the region, prompting alarm and close scrutiny, especially among Western Arctic nations wary of external involvement. For China, focusing on less politically sensitive areas, such as scientific collaboration or maritime safety, allows Beijing to build a track record of reliability. Meanwhile, China remains aware of the region’s competitive undercurrents, especially as global interest in the Arctic intensifies.

Pathways for cooperation

Trilateral cooperation enables the U.S., Russia, and China to leverage shared interests, reduce the risk of conflict, and build trust in a region that is increasingly militarized and environmentally vulnerable. Below are case studies illustrating feasible pathways.

Maritime safety and search and rescue

Arctic maritime traffic is expected to explode in the coming decades. Consequently, maritime safety and search and rescue, or SAR, to prevent and react to accidents, spills, and emergencies represent critical areas for international cooperation. The U.S., Russia, and China — all interested in the growing accessibility of Arctic routes — have a shared interest in minimizing risks, avoiding costly disasters, and ensuring rapid-response capabilities. Effective SAR cooperation means exchanging real-time information, conducting joint training exercises, and investing in infrastructure such as ports, communication systems, and coast guard assets.27

The North Pacific Coast Guard Forum, or NPCGF, is a practical example of how multilateral SAR cooperation can endure amid political tensions. Through the NPCGF, the U.S., Russia, China, and other regional stakeholders have jointly coordinated SAR and pollution response drills in the North Pacific.28In contrast, the Arctic Coast Guard Forum, or ACGF, excluded Russia due to the war in Ukraine, underscoring the fragility of some cooperative mechanisms. The NPCGF’s willingness to keep Russia at the table demonstrates that pragmatic cooperation can persist when mutual interests are strong. At a time when growing Sino–Russian patrols in and around the Arctic are raising alarms in the West, communication on maritime safety should be restored to a circumpolar level.29

There is a strong track record for U.S.–Russia SAR collaboration in the Bering Strait. Joint drills have shown that even adversarial nations can work together to save lives. These operations led to the International Maritime Organization, IMO, adopting new ship-routing schemes for the Bering Strait, significantly reducing the risk of collisions, which benefits every nation operating in the region.30

The logical next step is to fully integrate China into these safety frameworks. The Arctic Council’s Emergency Prevention, Preparedness and Response, EPPR, Working Group provides an avenue for broader inclusion. The EPPR is already facilitating the sharing of distress signals, ice reports, and best practices among member states. Precedents for safety coordination with China exist. When a Chinese researcher fell ill on the Xue Long (“Snow Dragon” in Chinese) icebreaker near Alaska in 2017, the U.S. Coast Guard coordinated a medical evacuation.31

To institutionalize this, SAR coordination must explicitly include Chinese vessels, with protocols for information sharing, joint exercises, and mutual support during emergencies. This is especially urgent given current realities: U.S. icebreaker capacity is stretched thin, and Russian assets are under pressure from sanctions and logistical constraints. In emergencies, it’s common that whoever is closest should render assistance, regardless of national flags. The risks are real: Sanctions have forced Russian oil tankers into riskier routes through the ice-covered Bering Strait, raising the probability of spills and accidents that could devastate fragile ecosystems and local communities without adequate insurance coverage.32China is an important stakeholder due to the nation’s growing involvement in shipping in this area.33

SAR is about more than just crisis response. It’s about building an environment of shared responsibility and risk management. This kind of cooperation would lead to lower shipping and insurance costs, improved safety, and a more stable Arctic environment that supports economic development. Without such cooperation, even a single accident could escalate quickly, triggering diplomatic rifts or environmental disasters.

Each country has its own approach to SAR, shaped by legal, operational, and political realities. Still, the IMO’s Polar Code, which all three countries have signed, establishes a framework of common standards.34Trilateral SAR projects could serve as confidence-building measures, leading to broader trust, safer waters, and greater benefits for communities in Alaska and beyond. In the long run, these cooperative efforts could lay the groundwork for more comprehensive agreements on Arctic governance.

Environmental protection

The Arctic is warming at a rate four times faster than the global average. This rapid transformation threatens not only the region’s unique ecosystems but also global weather patterns, coastal infrastructure, and food security. The region is effectively a planetary thermostat, and it is rapidly approaching irreversible tipping points that threaten the global climate system. Melting sea ice reduces the albedo effect, causing the ocean to absorb more heat, which in turn accelerates further melting. Thawing permafrost also threatens to release vast stores of methane — a greenhouse gas 80 times more potent than carbon dioxide in the short term.35These feedback loops could render mitigation efforts in other parts of the world insufficient.

The U.S., Russia, and China have complementary strengths that, if pooled, could drive significant progress on urgent challenges like melting sea ice, biodiversity loss, and pollution.36Each country brings something distinct to the table. The U.S. is a leader in remote sensing, satellite technology, and environmental monitoring. These tools provide critical data on ice cover, ocean currents, and ecosystem health. Russia has deep experience in Arctic navigation, icebreaker operations, and polar logistics. China is investing heavily in Arctic research stations and contributing substantial resources to Arctic science.

Figure 4: Agreement on Enhancing International Arctic Scientific Cooperation

The 2017 Agreement on Enhancing International Arctic Scientific Cooperation, signed by all Arctic Council states and observers like China, provides a robust platform for such work. Dozens of international science projects have emerged from this framework, demonstrating that countries can collaborate on common problems without sacrificing sovereignty or strategic advantage. This agreement has facilitated joint expeditions, harmonized research protocols, and enabled the exchange of personnel and samples across borders. Such cooperation builds a foundation of trust that can outlast political turbulence.37

Historical collaborations demonstrate the potential for science diplomacy. The Russian–American Long-term Census of the Arctic, or RUSALCA, ran from 2004 to 2015 and saw U.S. and Russian scientists jointly mapping the Chukchi and Bering Seas. Their efforts produced invaluable data on ocean chemistry, currents, plankton blooms, and shifts in commercial fish stocks. These insights inform both conservation strategies and sustainable fisheries management.38This kind of bilateral scientific groundwork should be expanded into trilateral initiatives, including China, enabling more comprehensive monitoring.

The Multidisciplinary Drifting Observatory for the Study of Arctic Climate, MOSAiC, expedition is another testament to what’s possible when the global scientific community unites: In 2019–2020, more than 600 researchers from 20 countries spent a year gathering data on Arctic ice.39While Russia and China participated only in supporting roles, their full engagement in future projects could drive even greater breakthroughs.

Cooperation here, too, requires policy adjustment. It requires a willingness to share proprietary data, pool resources, and distribute costs fairly. The benefits are substantial: shared satellite systems would reduce spending, and data flows would help fill gaps in global climate models. Unfortunately, current sanctions disrupt this flow, preventing Russian climate data from reaching international researchers and undermining everyone’s ability to forecast and adapt.40

The impact of these disruptions is tangible across scientific disciplines. In fisheries monitoring, when joint U.S.–Russian efforts in the Gulf of Alaska were suspended, critical knowledge was lost just as warming seas began to drive fish populations northward. Alaska now faces mounting uncertainty about the future of its fisheries, while Russia continues research on its own side of the Bering Strait.41However, there are precedents for restoring fisheries cooperation.

Norway maintains a successful, science-based fisheries partnership with Russia in the Barents Sea, proving that pragmatic cooperation can endure difficult political climates.42This model could be extended to China, which has signaled its concern for sustainable fishing by joining the Central Arctic Ocean Fishing Agreement.43If the three powers coordinate, they can set global precedents for responsible, science-driven governance of the Arctic commons. Such cooperation would protect ecosystems while supporting sustainable development. Crucially, these existential planetary risks outweigh the traditional security dilemmas and competition that currently dominate Western and Russian strategic thinking.

Military security dialogue

Establishing direct and sustained military security dialogue among the U.S., Russia, and China is essential to preventing the Arctic from becoming a new arena of confrontation. The region’s strategic importance is growing; U.S.–NATO and Russian naval forces routinely maneuver in the Barents Sea while China and Russia conduct joint exercises in the Bering Sea. As military activities intensify, so do the risks of accidental encounters, miscommunication, and unintended escalation.44

The Arctic’s geography amplifies these security concerns. It is the shortest route for intercontinental missiles and strategic bombers traveling between North America and Eurasia. Both the U.S. and Russia send nuclear-armed submarines under the ice, and Russia continues to test nuclear-powered cruise missiles and autonomous underwater vehicles in these waters.45Moscow frames its substantial military buildup as a necessary response to NATO’s increased regional presence, while U.S. and NATO officials argue that their activities are reacting to Russia.

To avoid a destabilizing spiral of suspicion and arms racing, the Arctic urgently requires concrete confidence-building measures. Effective mechanisms could include mandatory advance notice of large-scale military exercises and the establishment of dedicated communication hotlines to manage emergencies or clarify intentions in real time.46These steps would reduce the risk of dangerous misunderstandings and help maintain the Arctic as a zone of peaceful cooperation.

Uncertainty and secrecy tend to prompt riskier, more aggressive behavior. By promoting transparency and regular dialogue, the three powers can minimize the likelihood of miscalculations that could inadvertently trigger conflict. Even modest agreements, such as restricting certain provocative deployments or refraining from military activities near sensitive infrastructure, can significantly affect regional stability by signaling restraint.

These initial steps can serve as the foundation for more ambitious arms control negotiations. As mutual confidence grows, the Arctic could become a laboratory for innovative security arrangements, such as limited weapons-free zones, joint search-and-rescue operations, or multilateral crisis-response exercises. These measures would reduce the immediate risk of confrontation but also reinforce the broader principle that the Arctic should remain a region of low tension.

Obstacles to cooperation

Political and security frictions pose significant barriers to U.S.–Russia–China cooperation. These obstacles are not new or superficial but are rooted in longstanding geopolitical rivalries and divergent national security priorities. For Washington, the strategic calculus in the region is defined by deep suspicion of Chinese and Russian intentions, particularly around dual-use technologies and infrastructure that blur the lines between civilian and military applications.47

These anxieties are codified in official policy documents. The Pentagon’s 2024 Arctic Strategy explicitly singles out joint Russian–Chinese military exercises as direct threats to U.S. freedom of navigation and operational flexibility in the region.48Congress has adopted a posture that seeks to prevent any engagements that might “legitimize” China’s “near–Arctic” status. Legislative measures embedded in the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2025 require annual reporting on Russian and Chinese activities, restrict funding for joint scientific or commercial projects, and impose sanctions on entities involved in Sino–Russian collaborations.49

These defensive measures may have unintended consequences. Such policies inadvertently push Russia and China (and other BRICS members) closer together, creating a self-fulfilling prophecy of alignment that may undermine U.S. leverage. This dynamic risks solidifying the very strategic alignment Washington hopes to prevent.50

The ongoing war in Ukraine has only further complicated the picture. Multilateral cooperation in the Arctic, already fragile, has largely ground to a halt, with Western nations suspending or terminating most joint initiatives with Russia. The war has intensified the region’s conflict potential, prompting countries like Finland and Sweden to join NATO and sign bilateral defense agreements with the U.S., spurring increased military deployments and exercises by both NATO and Russia. Militarization raises the risk of accidental escalation in the Arctic.51

Despite media narratives about a resolute Russia–China Arctic partnership, the reality is complex. China sees vast economic and strategic opportunities in the Arctic, ranging from resource extraction to new shipping routes, but must also navigate Russia’s insistence on tight control and sovereignty-first policies.52Moscow remains wary of surrendering its autonomy or allowing Beijing too much influence over its Arctic territory. Moreover, Russian counterintelligence officials allegedly harbor deep concerns about China using Arctic mining companies and academic research to access strategic data.53Consequently, China treads carefully, eager to benefit economically but reluctant to become entangled in the escalating U.S.–Russia confrontation.54

Overcoming all these barriers will require more than incremental policy tweaks; it demands a paradigm shift. Instead of defaulting to suspicion, zero-sum thinking, and escalation, stakeholders must embrace restraint, diplomacy, and confidence-building measures. Even modest, well-targeted initiatives could start to rebuild the trust that eroded over the years.

Domestic politics, sanctions, and the pull of alliance structures continue to generate new obstacles. If these underlying drivers are not addressed, the Arctic risks becoming an increasingly volatile theater of great-power competition. This outcome is not predetermined. With deliberate policy adjustments that emphasize shared interests and pragmatic engagement, meaningful cooperation remains within reach.

Policy recommendations

The path forward for Arctic cooperation should be grounded in pragmatic, confidence-building measures that prioritize stability, inclusivity, and respect for sovereignty. The following recommendations are designed to be actionable and scalable:

Science and maritime safety

Tangible cooperation should begin with low-risk initiatives in science and SAR operations. Joint projects in areas like fisheries research, icebreaker operations, and climate monitoring can deliver swift and visible benefits to all parties. The ACGF should be revitalized with full Russian participation and China as an observer. Launching collaborative efforts modeled on successful initiatives such as the RUSALCA and MOSAiC expeditions, with China fully involved, would not only enhance research quality but also foster a spirit of reciprocity.

These efforts should be supported by lifting the bureaucratic barriers to collaboration and earmarking funding, such as $50 million from the fiscal year 2026 budget, for pilot projects. These initiatives should be accompanied by transparency measures to address concerns about dual-use technology and intellectual property. Success in these domains can build momentum for broader cooperation and demonstrate the value of engagement.

De-escalation channels

It is imperative to institutionalize direct, reliable U.S.–Russia–China communication channels focused on de-escalation and operational transparency in the Arctic. The rapid increase in maritime and air activity heightens the risk of accidents and misunderstandings.

Establishing a dedicated Arctic hotline for incident reporting, complemented by a secure digital platform for real-time vessel tracking and information sharing, would substantially reduce the risk of escalation. Such mechanisms could serve as early-warning systems, enabling all parties to quickly clarify intentions and coordinate emergency responses, thereby minimizing the risk of miscalculation.

Cross-border diplomacy

It is vital to restore cross-border cooperation between Arctic residents and Indigenous peoples with simplified visa procedures. A precedent for this is the 1989 Agreement on Mutual Visits by Inhabitants of the Bering Strait Region.55Born from the thaw of the Cold War, this accord allowed Indigenous peoples from Alaska and Chukotka to cross the “Ice Curtain” for cultural exchanges and family reunifications without standard visa requirements. For decades, this agreement advanced soft power and cultural diplomacy.

The 1989 agreement technically remains in force, as neither the U.S. nor Russia has formally repealed it. However, it is operationally dormant and effectively suspended in practice. Revitalizing this protocol would uphold Indigenous rights enshrined in U.N. declarations and serve as a local-level confidence-building measure. It would be a reminder that the Arctic is a homeland of shared communities before it is a strategic theater.

Revitalizing the Arctic Council

The U.S. should champion the restoration of the Arctic Council as a robust multilateral platform, advocating for Russia’s full engagement and more active integration of China as an observer. Restoring the Council would revitalize critical projects and restore international funding, such as the funding suspended by Russia in 2024.56

By ensuring all key stakeholders have a voice, the Arctic Council can reclaim its role as the primary venue for peaceful Arctic governance. Isolating key stakeholders from the Arctic Council could cause them to explore alternative frameworks for regional cooperation under the auspices of the BRICS or other groupings.

Military restraint

Demonstrating military restraint in the region is crucial for building trust and reducing the threat of unintended conflict. The U.S., Russia, and China should commit to scaling back non-essential military exercises in the Arctic and to providing advance notification for any significant maneuvers or deployments. President Trump has already called for a trilateral arms control framework involving Russia and China, emphasizing the need to reduce nuclear arsenals and military budgets.57The Arctic could be a suitable place to start such demilitarization.

Developing an Arctic–specific notification protocol, potentially under the auspices of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe or the Arctic Council, would help institutionalize these commitments.58Regular trilateral meetings of military and technical experts, with findings directly informing policy, could oversee compliance and facilitate the exchange of best practices. As trust builds, these meetings could gradually pave the way for more ambitious arms control and security arrangements.

Conclusion

Arctic cooperation between the U.S., Russia, and China offers profound positive-sum potential. The region’s unique vulnerabilities and potential demand a collaborative approach that transcends rivalry. By embracing these recommendations, the U.S. can lead a new era of Arctic cooperation that advances stability.

Policymakers must recognize that the hierarchy of threats in the Arctic has fundamentally changed. The risk of military conflict pales in comparison to the imminent dangers of environmental disasters, climate tipping points, and feedback loops.

Through sustained engagement, targeted confidence-building, and a renewed commitment to diplomacy, the U.S. can help lead an Arctic renaissance of peaceful collaboration. In doing so, the U.S. will demonstrate to the world that diplomacy remains a powerful tool for addressing even the most complex and contentious challenges of the 21st century.

Program

Topics

Countries/Territories

Citations

Pavel Devyatkin, “Did the Alaska Summit Usher in a New Ice Age?” Responsible Statecraft, Aug. 20, 2025, https://responsiblestatecraft.org/trump-putin-arctic/. ↩

Barak Ravid and Dave Lawler, “Trump’s Full 28-Point Ukraine–Russia Peace Plan,” Axios, Nov. 20, 2025, https://www.axios.com/2025/11/20/trump-ukraine-peace-plan-28-points-russia; Pavel Devyatkin, “A New Age for U.S.–Russia Arctic Cooperation?” The Nation, March 18, 2025, https://www.thenation.com/article/world/russia-putin-trump-climate-diplomacy-war/. ↩

Ryan Mancini, “What We Know About Trump’s Greenland Deal,” The Hill, Jan. 22, 2026, https://thehill.com/homenews/administration/5701884-trump-greenland-deal-framework-details/. ↩

Pavel Devyatkin et al., “Restoring Arctic Exceptionalism: The Path Toward Sustainable Cooperation,” Quincy Institute, July 28, 2025, https://quincyinst.org/research/restoring-arctic-exceptionalism-the-path-toward-sustainable-cooperation/. ↩

Iselin Stensdal and Gørild Heggelund, eds., China–Russia Relations in the Arctic: Friends in the Cold? (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan Cham, 2024), https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-63087-3. ↩

Pavel Devyatkin, “The Arctic Strategic Triangle: United States—China—Russia Competition and Cooperation,” in China–Russia Relations in the Arctic. ↩

“Presidential Decision Directive/NSC-26,” The White House, June 9, 1994, https://irp.fas.org/offdocs/pdd/pdd-26.pdf. ↩

“National Security Presidential Directive 66 and Homeland Security Presidential Directive 25,” The White House, Jan. 9, 2009, https://irp.fas.org/offdocs/nspd/nspd-66.htm. ↩

“National Strategy for the Arctic Region,” The White House, May 10, 2013, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/docs/nat_arctic_strategy.pdf. ↩

Pavel Devyatkin, “U.S.–Russia Arctic Cooperation: Strategic Ebbs and Flows,” Strategic Analysis 0, no. 0 (2025): 1–11, https://doi.org/10.1080/09700161.2025.2457794. ↩

“National Strategy for the Arctic Region,” The White House, Oct. 7, 2022, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/National-Strategy-for-the-Arctic-Region.pdf. ↩

“Remarks by President Biden in Press Conference – Geneva, Switzerland,” U.S. Mission to International Organizations in Geneva, June 17, 2021, https://geneva.usmission.gov/2021/06/17/remarks-by-president-biden-in-press-conference-geneva-switzerland/. ↩

“2024 Arctic Strategy,” U.S. Department of Defense, July 22, 2024, https://media.defense.gov/2024/Jul/22/2003507411/-1/-1/0/DOD-ARCTIC-STRATEGY-2024.PDF. ↩

“Putting America First In International Environmental Agreements,” The White House, Jan. 20, 2025, https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/01/putting-america-first-in-international-environmental-agreements/. ↩

Marwa Rashad and Anna Hirtenstein, “Exclusive: U.S. Mulled Use of Russia Icebreakers for Gas Development Ahead of Summit — Sources,” Reuters, Aug. 15, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/us-mulled-use-russia-icebreakers-gas-development-ahead-summit-sources-2025-08-15/. ↩

Andrew S. Erickson, “Competitive Coexistence: An American Concept for Managing U.S.–China Relations,” The National Interest, Jan. 30, 2019, https://nationalinterest.org/feature/competitive-coexistence-american-concept-managing-us-china-relations-42852. ↩

“Global Trends 2040: A More Contested World,” Office of the Director of National Intelligence, 2021, https://www.dni.gov/index.php/gt2040-home/scenarios-for-2040/competitive-coexistence. ↩

Pavel Devyatkin, “Arctic Exceptionalism: A Narrative of Cooperation and Conflict from Gorbachev to Medvedev and Putin,” The Polar Journal 13, no. 2 (2023): 336–57, https://doi.org/10.1080/2154896X.2023.2258658. ↩

“Foundations of the State Policy of the Russian Federation in the Arctic to 2020 and Beyond [Основы государственной политики Российской Федерации в Арктике на период до 2020 года и дальнейшую перспективу],” Government of the Russian Federation, Sept. 18, 2008, http://government.ru/info/18359/. ↩

“Strategy for Development of the Arctic Zone of the Russian Federation and Provision of National Security for the Period up to 2035 [Стратегия Развития Арктической Зоны России и Обеспечения Национальной Безопасности До 2035 Года],” The Kremlin, Feb. 27, 2023, http://www.kremlin.ru/acts/bank/45972. ↩

“Arctic Produces about 6% of Russia’s GDP, around 10% of Its Exports — Minister,” TASS, Sept. 19, 2025, https://tass.com/economy/2018977. ↩

“China’s Arctic Policy,” State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China, Jan. 26, 2018, https://english.www.gov.cn/archive/white_paper/2018/01/26/content_281476026660336.htm. ↩

Hong Nong, China and the United States in the Arctic: Exploring the Divergence and Convergence of Interests (Washington: Institute for China–America Studies, 2022), https://chinaus-icas.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/China-US-Arctic-Report-10.2022-Final.pdf. ↩

Rory O’Connor, “The Dragon, The Bear, and The Eagle,” The Monitor, April 22, 2025, https://uscnpm.substack.com/p/the-dragon-the-bear-and-the-eagle. ↩

Zhenmin Liu, “Following the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence and Jointly Building a Community of Common Destiny,” Chinese Journal of International Law 13, no. 3 (2014): 477–80, https://doi.org/10.1093/chinesejil/jmu023. ↩

Min Pan and Henry P. Huntington, “China–U.S. Cooperation in the Arctic Ocean: Prospects for a New Arctic Exceptionalism?” Marine Policy 168 (October 2024): 106294, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2024.106294. ↩

Andreas Østhagen, “Arctic Coast Guards: Why Cooperate?” in Routledge Handbook of Arctic Security (Philadelphia: Routledge, 2020). ↩

Rebecca Pincus, “Coast Guard Co-Operation in the Arctic: A Key Piece of the Puzzle,” in Crisis and Emergency Management in the Arctic, eds. Natalia Andreassen and Odd Jarl Borch (Milton Park: Routledge, 2022). ↩

Pavel Devyatkin, “Russia–China Arctic Security Cooperation: Countering a U.S. Threat?” in The “New” Frontier: Sino–Russian Cooperation in the Arctic and Its Geopolitical Implications, eds. Niklas Swanström and Filip Borges Månsson (Stockholm: Institute for Security and Development Policy, 2025), https://www.isdp.eu/publication/sino-russian-cooperation-in-the-arctic-and-its-geopolitical-implications/. ↩

Andrey Todorov, “Shipping Governance in the Bering Strait Region: Protecting the Diomede Islands and Adjacent Waters,” Marine Policy 146 (December 2022): https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2022.105289. ↩

“USCG Medevacs Patient from Chinese Icebreaker,” The Maritime Executive, Sept. 25, 2017, https://maritime-executive.com/article/uscg-medevacs-patient-from-chinese-icebreaker. ↩

Paul Fuhs, “What Alaska Can Gain from the Trump–Putin Talks,” Anchorage Daily News, Aug. 24, 2025, https://www.adn.com/opinions/2025/08/13/opinion-what-alaska-can-gain-from-the-trump-putin-talks/. ↩

Laura Paddison, “This Sea Route Has Been Dismissed as Too Treacherous. China’s Taking the Risk,” CNN, Oct. 3, 2025, https://www.cnn.com/2025/10/03/climate/china-arctic-shipping-northern-sea-route. ↩

Andrey Todorov, “Arctic Shipping: Trends, Challenges, and Ways Forward,” The Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, Aug. 23, 2023, https://www.belfercenter.org/publication/arctic-shipping-trends-challenges-and-ways-forward. ↩

Matthew L. Druckenmiller et al., “Arctic Report Card 2025,” National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, https://arctic.noaa.gov/report-card/report-card-2025/. ↩

Jennifer Spence et al., “Arctic Research Cooperation in a Turbulent World,” Science 387, no. 6734 (2025): 598–600, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adr7939. ↩

Paul Arthur Berkman et al., “The Arctic Science Agreement Propels Science Diplomacy,” Science 358, no. 6363 (2017): 596–98, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaq0890. ↩

Pavel Devyatkin, “Environmental Détente: U.S.–Russia Arctic Science Diplomacy through Political Tensions,” The Polar Journal 12, no. 2 (2022): 322–42, https://doi.org/10.1080/2154896X.2022.2137091. ↩

Devyatkin, “Environmental Détente.” ↩

Angelina Flood, “Arctic Experts Highlight Importance of Track 2 Cooperation Between U.S. and Russia,” Russia Matters, Jan. 15, 2025, https://www.russiamatters.org/blog/arctic-experts-highlight-importance-track-2-cooperation-between-us-and-russia. ↩

Fuhs, “What Alaska Can Gain from the Trump–Putin Talks.” ↩

“Norwegian–Russian Fisheries Negotiations to Be Held in December,” Government of Norway, Nov. 21, 2025, https://www.regjeringen.no/en/whats-new/norsk-russiske-fiskeriforhandlinger-avholdes-8.-12.-desember/id3140362/. ↩

Min Pan and Henry P. Huntington, “A Precautionary Approach to Fisheries in the Central Arctic Ocean: Policy, Science, and China,” Marine Policy 63 (2016): 153–57, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2015.10.015. ↩

Pavel Devyatkin, “The Rising US–NATO–Russia Security Dilemma in the Arctic,” Responsible Statecraft, Sept. 11, 2025, https://responsiblestatecraft.org/arctic-nato-russia-2673981485/. ↩

Atle Staalesen, “More Nuclear-Powered Weapons Testing Coming up in the Arctic,” Arctic Today, July 1, 2025, https://www.arctictoday.com/more-nuclear-powered-weapons-testing-coming-up-in-the-arctic/. ↩

Alexander MacDonald, “A Menu of Arctic Specific Confidence Building and Arms Control Measures,” in Arctic Yearbook 2024, https://arcticyearbook.com/arctic-yearbook/2024/2024-scholarly-papers/524-a-menu-of-arctic-specific-confidence-building-and-arms-control-measures. ↩

Barry Scott Zellen, “A Grand Illusion: America’s Anti-China Arctic Policy Is Rooted in Paranoia and Political Bias, Not Strategic Reality,” The Arctic Institute, Oct. 21, 2025, https://www.thearcticinstitute.org/grand-illusion-americas-anti-china-arctic-policy-rooted-paranoia-political-bias-strategic-reality/. ↩

“2024 Arctic Strategy,” U.S. Department of Defense. ↩

Sen. Jack Reed, “S.4638 – 118th Congress (2023-2024): National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2025,” July 8, 2024, https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/senate-bill/4638/text. ↩

Matthias Finger, “On the BRICS of War: What Future for the Governance of the Global Arctic?” in Global Arctic, ed. Gunnar Rekvig and Matthias Finger (Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore, 2025), https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-96-4868-9_17. ↩

Florian Vidal, “The Arctic in the Era of Global Change: An International Security Perspective,” in Global Arctic. ↩

Anders Edstrøm et al., “Cutting Through Narratives on Chinese Arctic Investments,” The Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, June 23, 2025, https://www.belfercenter.org/research-analysis/china-arctic-investments. ↩

Jacob Judah et al., “Secret Russian Intelligence Document Shows Deep Suspicion of China,” New York Times, June 7, 2025, https://www.nytimes.com/2025/06/07/world/europe/china-russia-spies-documents-putin-war.html. ↩

Roman Zhilin, “A Pragmatic Approach to Conceptual Divergences in Russia–China Relations: The Case of the Northern Sea Route,” The Arctic Institute, Nov. 4, 2025, https://www.thearcticinstitute.org/pragmatic-approach-conceptual-divergences-russia-china-relations-case-northern-sea-route/. ↩

“Bering Strait Visa-Free Travel Program,” U.S. Department of State, https://www.state.gov/bering-strait-visa-free-travel-program. ↩

Jennifer Spence, “Russia Suspends Funding for the Arctic Council: Wake up Call Not Death Knell,” High North News, Feb. 15, 2024, https://www.highnorthnews.com/en/russia-suspends-funding-arctic-council-wake-call-not-death-knell. ↩

Xiaodeng Leng, “Trump Says U.S. Is Open to Nuclear Talks,” Arms Control Association, March 2025, https://www.armscontrol.org/act/2025-03/news/trump-says-us-open-nuclear-talks. ↩

Benjamin Schaller, “Defusing the Discourse on ‘Arctic War’: The Merits of Military Transparency and Confidence- and Security-Building Measures in the Arctic Region,” in OSCE Yearbook 2017, OSCE, (Nomos: Institute for Peace Research and Security Policy, 2018), 213–26, https://doi.org/10.5771/9783845290423-213. ↩